With with, with or with? Posted by hulda on Apr 11, 2014 in Icelandic grammar

“Mig langar að tala við þig, hjá þér, og þá langar mig að tala með þér upp á sviði.” Put this sentence in an online translator and you get “I want to talk to with you and allow me to speak with you on stage” as a translation. Icelandic prepositions are endlessly confusing and here are some of the worst perpetrators – við, með and hjá.

I have to admit that the example sentence is written in a confusing manner and sounds clumsy. Still, I wanted to show you a technically correct sentence with as many prepositions that can be translated exactly the same way – as “with” – while also having a different meaning in the context, and this is the best I could come up with. By the way, “og” can occasionally also be translated as “with” although it’s not a preposition at all! Translating the example sentence as “I’d like to talk with you with you with then I’d like to talk with you on stage” makes even less sense than the translator’s attempt, so let’s look at what’s actually going on here.

Og

Easiest one to pull apart from the confusion is, of course, og. It means “and” and works like the English “with” does when it’s used instead of “and”. This means that in the grand majority of times when you see og it’s almost always translatable only as “and”, therefore just thinking of it as an “and” is your easy shortcut to understanding what type of a “with” it is. As mentioned it’s not a preposition, I’m only adding it here for curiousity value. 😉

Hjá

Moving towards the more difficult ones, hjá comes next. Hjá demands that the next word is in þágufall (= dative) and most commonly it translates as “at”, although “with” is also a possibility f.ex. in “að sofa hjá” (= to sleep with, to have sex with). To define it means “at” as being next to/beside something that’s not a living thing: ég er núna hjá Hörpu (= right now I’m beside the concert hall Harpa).

There are even more translation possibilities and not all of them deal with inanimate objects, for example “miðar eru seldir hjá kórfélögum” means “tickets are sold by choir members” and “(að vera) hjá Hulda/Valdísi/Gunnlaugi” means being at these people’s apartments, not just hanging out with them or even being in their presence (they don’t necessarily even have to be with you). “Hvað er númerið hjá neyðarlínunni?” (= What’s the number for emergency line?), Hann býr hjá henni (= He lives at her place, as in right there with her and not f.ex. next door to her). Hjá is also used as a forskeyti (= prefix) in words such as hjáleið (= detour) and hjákona (= mistress).

Well, now we have narrowed the example sentence down to “I’d like to talk with you at your place and then I’d like to talk with you.” Still a bit confusing but at least it’s beginning to make sense now, so let’s see the difference between við and með.

Við

First of all, if you already know a Scandinavian language now’s a good time to forget everything you know of similar sounding prepositions in that language. Icelandic is that one special snowflake in the Germanic language family that does things differently and this has caused me much confusion along the way.

Við tends more towards þolfall (= accusative) but þágufall happens f.ex. with the verb að taka (= to take), if the meaning in context is “to receive” -“Ég talaði ekki við hana en ég tók við peningum af henni” (= I didn’t talk with her but I accepted/took the (offered) money from her, notice the first við governs þolfall and the second þágufall). Þágufall is also used if you’re talking about a reaction to something, f.ex. “Hvernig brást hann við því?” (= How did he react to that?)

As its most common usage við is another way of saying “at” such as in “við hliðina á (right next to sth/at the side of place X). It can also mean “by” – ég ætla að biða við bílinn (= I’m planning to wait by the car). If you see a við next to a verb, pay special attention because it sometimes changes the meaning of the verb: “að gera við” actually means “to fix”, “að líka við” means to like – líka here is a borrowed word from English, actually. If you see a combination “leitast við” it does not mean “search at” but “to try” in formal speech. “Eiga við” can mean “to tamper/fiddle with” and so forth.

Here’s the super bad news for you: there is no rule to using við, you have to learn each situation that it appears in by heart. This will be your life-long battle if Icelandic is not your mother tongue, but on the upside this is what makes studying languages so interesting that if you’re already here reading this blog and wanting to learn Icelandic you’re probably both aware of it and are ok with it. The pay for the work is in the work itself for those who have a passion for languages. 🙂

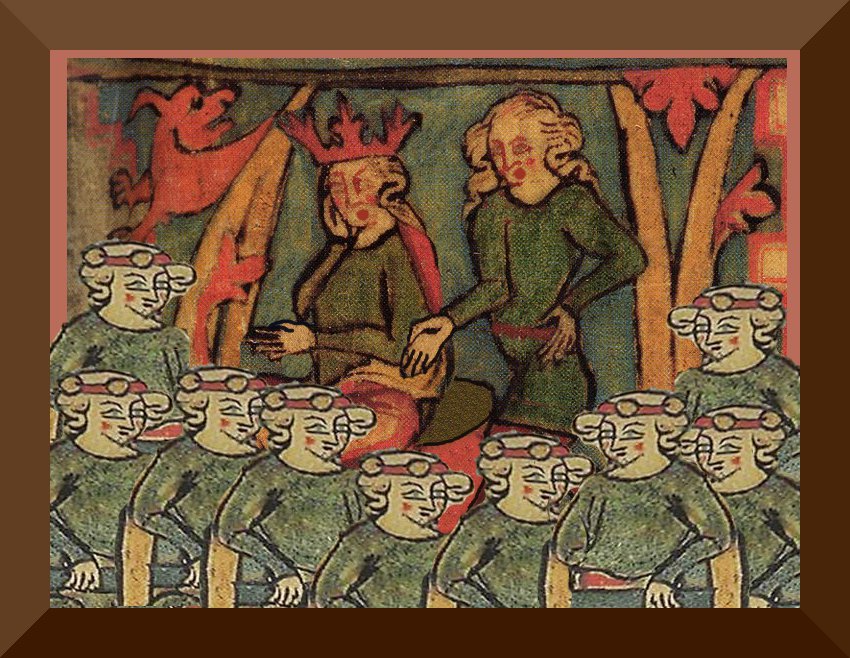

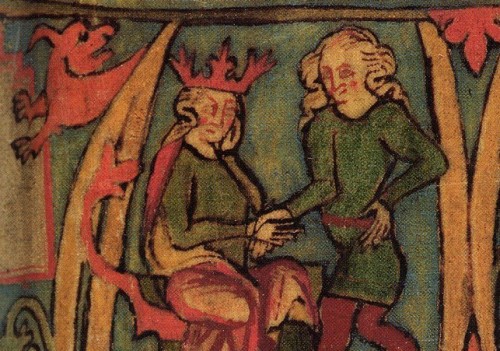

Haraldur talar með Hálfdani upp á sviði.

Haraldur talar með Hálfdani upp á sviði.

Með

Með, on the other hand, really does tend to translate as “with” in most of the cases although it, too has nuances depending on the situation. If you’re hanging out with someone the correct preposition to use indeed is með, and it tends to apply to all living things that you might be with. However, it’s also a crucial part of some verbs – “að vera með” (= to have, in the meaning that you’re carrying something with or on yourself) comes to mind as the most obvious example! This verb is important to get right by the way, I’ve written about it and the other two ways of saying “to have” here.

Með is one of those prepositions that doesn’t strictly govern any case, although þágufall is more common. There’s one important difference though – if you’re using it to describe with what item you did what, such as “með hamri” (= with a hammer) you’re likelier to use þágufall, but if you use it in the að vera með form you should use þolfall.

So what’s the deal with the example sentence?

In many cases the prepositions simply have a defined meaning depending on the verb they appear with, and that is the case of tala við vs. tala með. “Að tala við einhvern/einhverja” means that you’re having a discussion with someone, as in you are talking with them and (hopefully) listening to their input creating a dialogue. If you were to use “að tala með einhverjum/einhverri“… well, it’s almost entirely incorrect in Icelandic. It doesn’t make sense on its own without some addition to it that explains the weird choice of preposition, such as “upp á sviði” that I’ve used here. The nuance meaning within tala með is that although you’re talking with them your talking partner is not your audience. You two may bey talking together but you’re not talking to each other.

Confusing enough? 😀 If we now look at the original example sentence again the meaning should come easily through: “I’d like to have a discussion with you, at your place, and then I’d like to deliver a talk with you on stage.”

Today I’m going to recommend one song instead of a band, because it fits the theme of today’s post so well and is an excellent study piece for how the prepositions work in practice: Sálin Hans Jóns Míns is the band and song is called Hjá þér (link).

The images used in this blog post are originally from Flateyjarbók. Sources: 1, 2.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

About the Author: hulda

Hi, I'm Hulda, originally Finnish but now living in the suburbs of Reykjavík. I'm here to help you in any way I can if you're considering learning Icelandic. Nice to meet you!

Comments:

Neil Eyford:

I’m very happy to have found your wonderful site. As someone quite keen to learn my ancestral language, I think it is very well composed and helpful to my efforts. I’m grateful and appreciative of your efforts.

Regards

hulda:

@Neil Eyford Nice to meet you Neil, I’m glad you like my writings! I have deep respect for people who hold onto their own history with enough seriousness as to take interest in the language – but then again Icelandic is such a difficult one to master that I have some serious respect for anyone wanting to learn it, no matter what the reason. 😀

Amanda:

Hi Hulda,

I’ve only recently begun studying Icelandic and am so glad to have found your posts here! The insights into this amazing language are much appreciated.

I have some questions regarding studying in Iceland as a foreigner, I don’t know if you could point me to some resources so I could learn more? Thanks very much.

hulda:

@Amanda Hi Amanda, and welcome! I’m glad to hear I’ve managed to convey some of the feelings that I have for this language, both good (it’s an amazing and beautiful language) and bad (the grammar will drive me crazy one day). 😀

There’s one really fun and informative blog written by a foreigner studying Icelandic in Iceland, and besides her own experiences you’ll find lots of other sources through her blog as well. May I present: Eth & Thorn.

http://ethandthorn.wordpress.com/

Antonia:

I am SO grateful to you for this. Thank you for taking the time to write it and for explaining it all so clearly!

hulda:

@Antonia I’m glad I could help! I still remember how horribly confusing it was to learn this. 🙂