Can borrowing words from other languages unlock new thoughts and feelings? Posted by Transparent Language on Mar 13, 2017 in Archived Posts

Guest Post by Sean Fitzsimons – linguistics graduate, writer and researcher.

Every language has its limits. Languages cannot simply stretch their semantic fields to describe what others can in remarkable detail. By learning new languages, we can not only enrich our communication skills and cultural understanding, but also tap into thoughts which we previously had no concise way of expressing.

While languages are constantly evolving, they are also reflecting the community and systems they are spoken in. Perhaps one of the most well-known examples of a language expanding in terminology to suit the practical needs of its speakers, is within the various Inuit dialects and their many ways of referencing and categorizing snow.

Not every language necessarily can put such a large lexicon of snow references to good use. However, there are plenty of concepts which are universally common and take on deeper, more specific meanings, depending on what language you are using.

With a little more exploration, it becomes clear how many holes actually exist in the vocabulary of our own mother tongues. Just like any language, English lacks words to describe particular thoughts and feelings – lexical gaps that are easy to miss. We’ve all felt emotions that we can’t quite put into a single word, yet there is a good chance another language out there probably can.

Expressing love, for example, may seem straightforward in one sense. The ways in which languages verbally interpret love, though, can vary hugely. Take a familiar boy-meets-girl scenario often depicted in teen films:

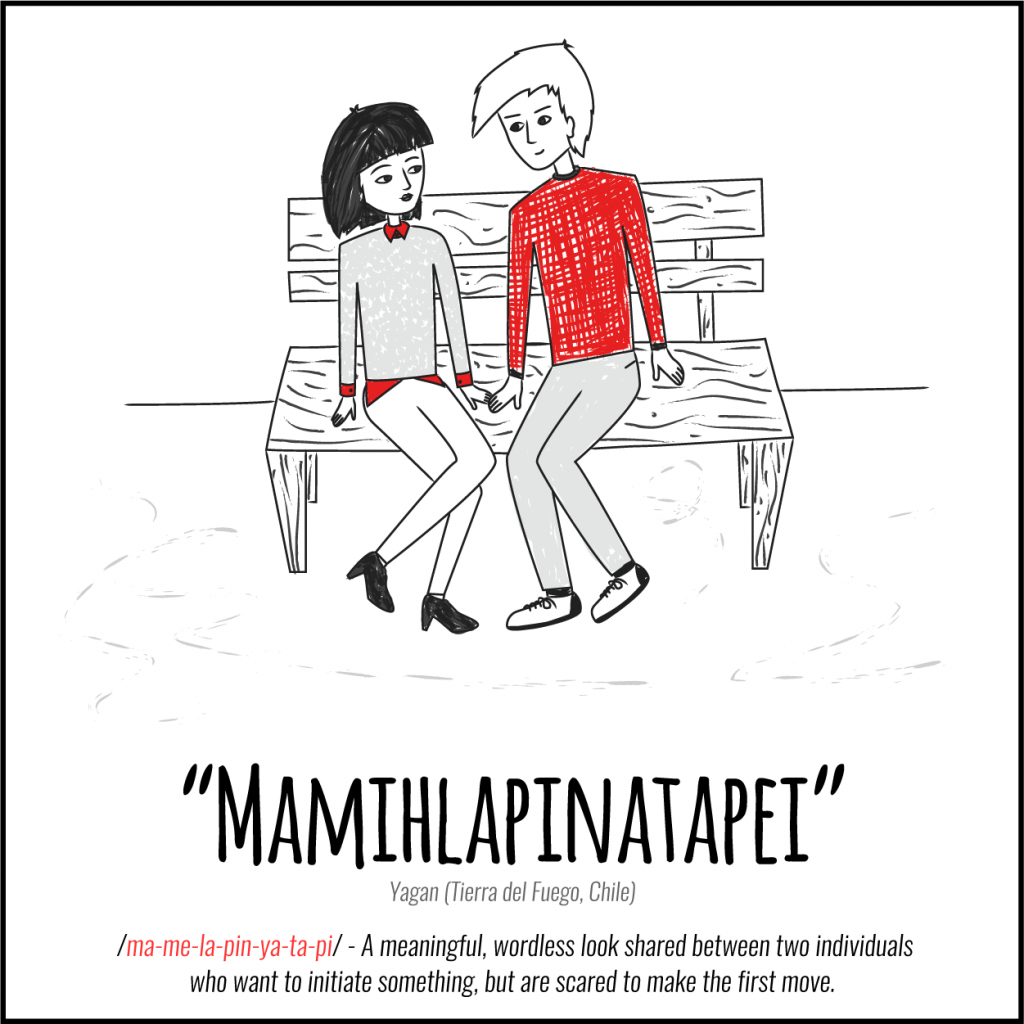

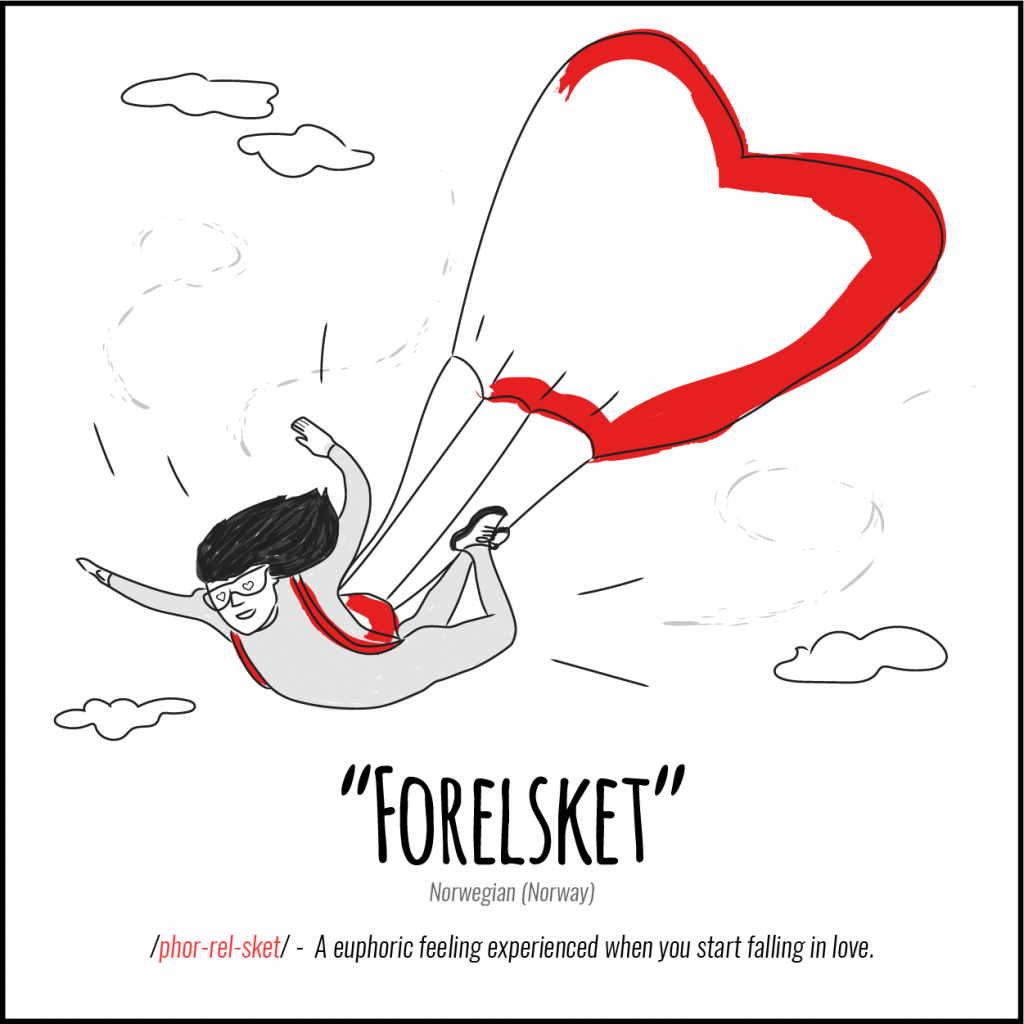

Two people’s eyes meet, they yearn to initiate something but are both afraid of doing so. Rather than keeping this awkward scenario pent up inside them, a speaker of Yágan in Tierra del Fuego could call this ‘mamihlapinatapai’. By the time one of them does (hopefully) make the first move, assuming the pair hit it off, they will begin to experience the sensation of first falling in love which Norwegians handily call ‘forelsket’.

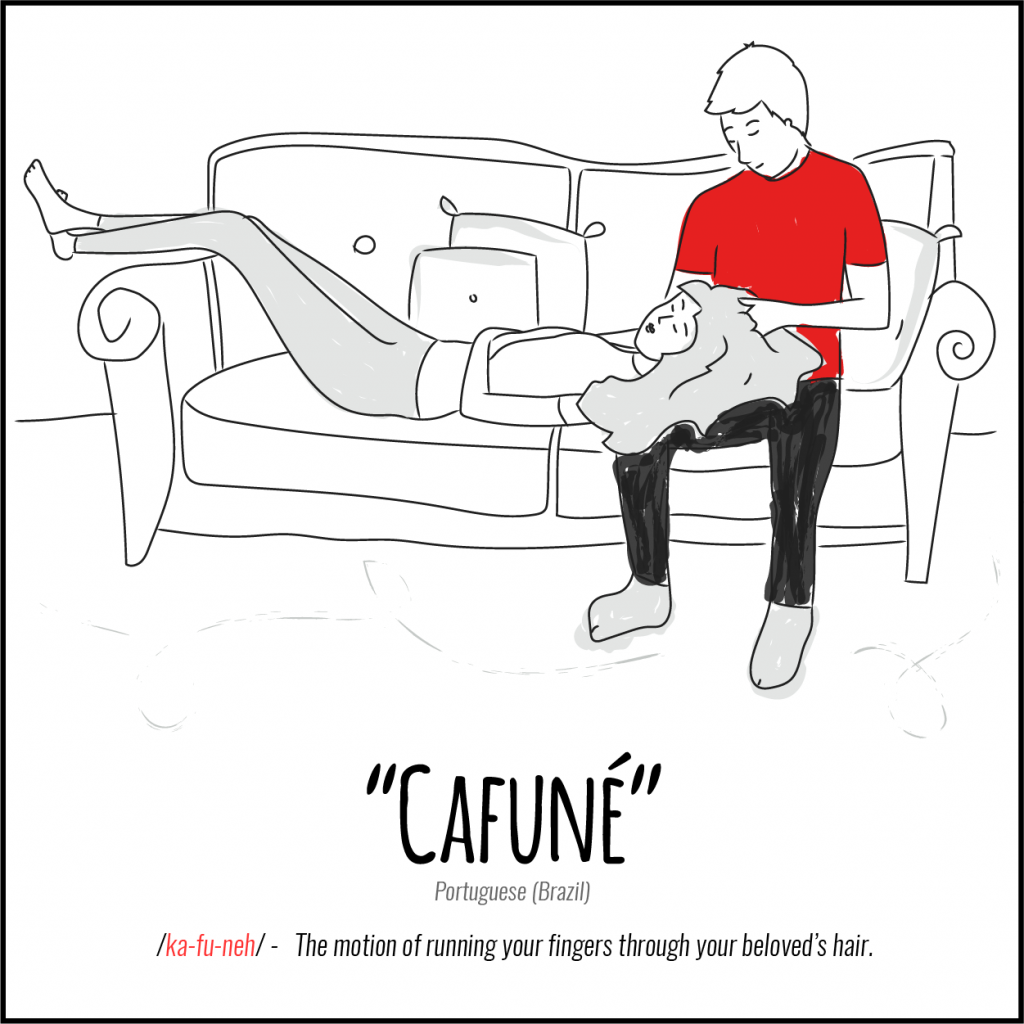

As the romance grows, so too does their time spent together, it may even get to the stage where being apart from each other evokes a strong emotional pain that Hindi speakers refer to as ‘viraag’. Once the ‘viraag’ has become all too much to handle, and the lovestruck guy drives over to the girl’s house, an Inuit speaker would call the sense of anticipation in eagerly awaiting someone to arrive at their home ‘iktsuarpok’.

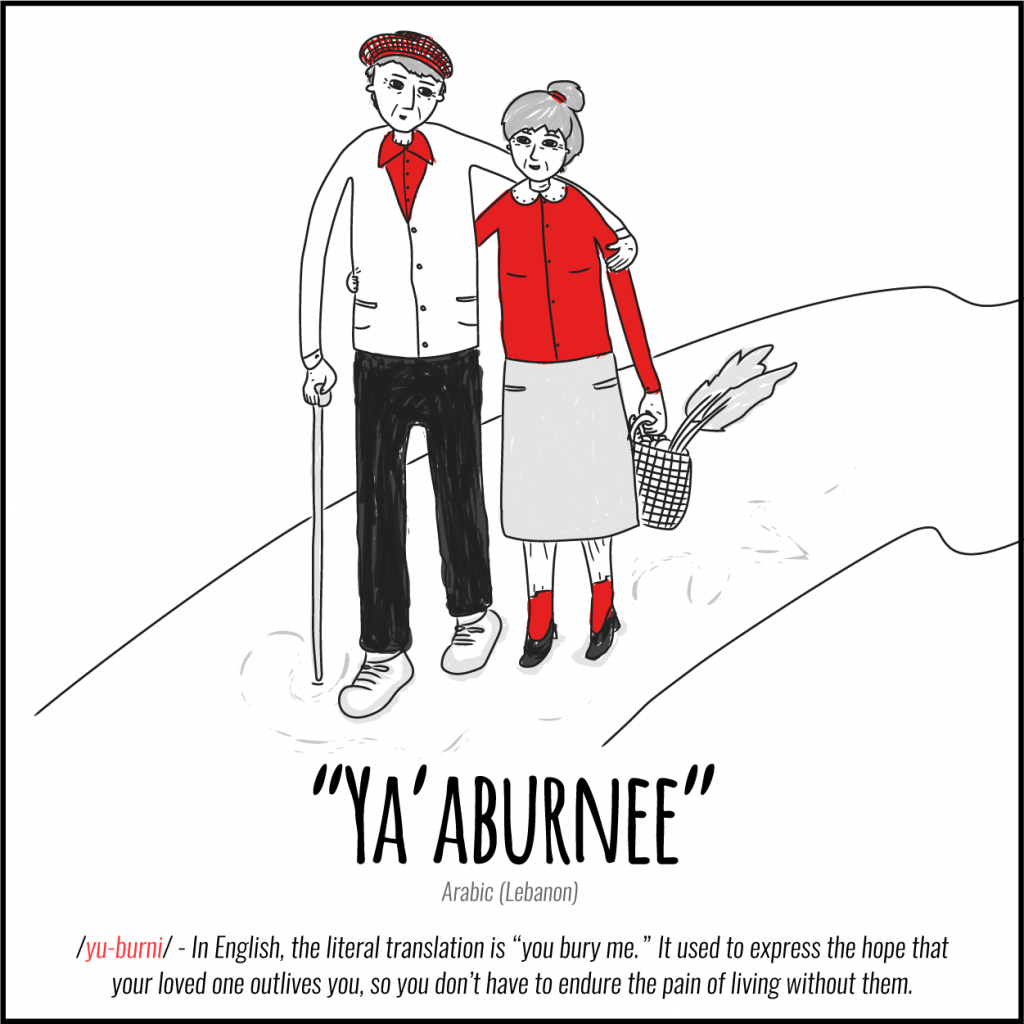

Fast forward fifty years after a lifetime together, where neither of the couple can imagine life without the other, a romantic sentiment in itself, but they could go one further by adopting the Arabic term ya’burnee. This translates literally as ‘you bury me’ and expresses the hope of dying before their partner, to avoid the pain of enduring a life without them.

These are what we might call “untranslatable” words and they extend far beyond the realms of love and romance, but stand for feelings and moments to which most of us can easily relate. The act of gazing vacantly into the distance without any thoughts taking hold has a name in Japanese called ‘boketto’. In Chinese, the sense of perfection or accomplishment after a job well done is known as ‘yuan bei’. Being able to cognitively empathise with someone’s thoughts without even saying a word is called ‘mitdenken’ by German speakers.

All of the words mentioned so far have a broadly feel-good sense about them, and research suggests harnessing the power of positive foreign terms in our own everyday language could even improve our personal wellbeing. However, it isn’t only the positive lexicography that is sometimes missing in our vocabularies. A deep, grief-stricken homesickness for a departed entity is coined in Welsh as ‘hiraeth’. Russian speakers use the term ‘tocka’ to describe an aching of the soul over a completely unknown cause. Melancholic longing for something (or someone) that might never return to us is simply called ‘saudade’ in Portuguese.

We might not adopt so many of these words for regular usage any time soon, but there is something quite satisfying about finding a single term to capture a concept or feeling we’ve never been able to properly define before. Although expanding your vocabulary in this way is unlikely to take you on a journey of emotional discovery, it does help us appreciate just how nuanced languages can be in their evolution and understanding of human feelings.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

Lee Donovan:

Though I believe your hearth was in the right place with the Russian, the use of Latin characters is misused, here. If you don’t have access to a Cyrillic keyboard, the best course would have been to use all capitals, as in “TOCKA,” otherwise, the word comes off looking as if it were to be pronounced as “tokka.” 🙂