September as the Romans Saw It: Agriculture and Art Posted by Brittany Britanniae on Sep 7, 2016 in Roman culture, Uncategorized

Salvete Omnes! I hope everyone is well! Let us welcome in the new month with a look at how the Ancient Romans thought of the month of September in iconography and agricultural practice.

![Two men crushing grapes on the September panel from the 3rd-century mosaic of the months at El Djem, Tunisia (Roman Africa):[1] the vintage is a characteristic activity of the month in Roman art. Courtesy of Ad Meskens and Wikimedia Commons.](https://blogs.transparent.com/latin/wp-content/uploads/sites/15/2016/09/september-fragment-of-a-mosaic-with-the-months-of-the-year-Ad-Meskens-350x263.jpg)

Two men crushing grapes on the September panel from the 3rd-century mosaic of the months at El Djem, Tunisia (Roman Africa):[1] the vintage is a characteristic activity of the month in Roman art. Courtesy of Ad Meskens and Wikimedia Commons.

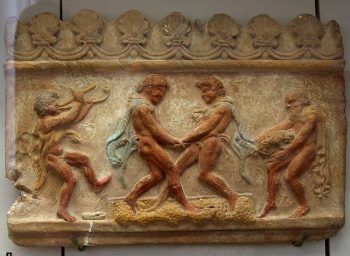

Architectural relief plagues – vintage and pla tramp grapes. Harvesting grapes. Rome 2nd half 1 c. AD. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

This was the last stretch of time as people eagerly awaited the harvest and the bounty of their summer work and their observations of other ceremonies that were meant to appease other gods to ensure the safety of their crops.

A pre-Julian Roman calendar found in the ruins of Nero’s villa at Antium (Anzio). Shows September (abbreviated SEP) at the top of the ninth column. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

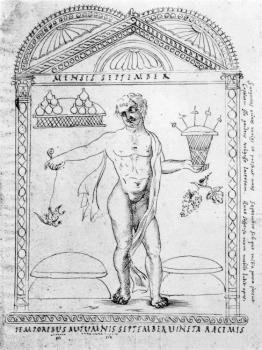

The Chronography of 354 is a 9th century reproduction of the original 4th century illustrated calendar created by the Roman Filocalus. This calendar featured not only illustrations for each month but also included tetrastichs, a poem consisting of four lines, that describe the major theme of the month according to the ancient Romans.

Here is the illustration and tetrastich, translated by Doro Levi in “The Allegories of the Months in Classical Art”, dedicated to it:

Month of September from the Chronography of 354 by the 4th century kalligrapher Filocalus. 17th century pen-drawing of the original. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

SEPTEMBER

Turgentes acinos, varias et praesecat uvas

September, sub quo mitia poma iacent,

Captivam filo gaudens religasse lacertam,

Quae suspensa manu mobile ludit opus.

“September cuts off the turgid grapes of all kinds; on the ground, ripe fruits are lying. He is amused by the wrigglings made by a captive lizard which he holds hanging from a thread.”

Tempora maturis, September, vincta racemis

Velate e numero nosceris ipse tuo.

“O September covered with veils and with your temples adorned with ripe grapes, your name will be explained by your own number (in the order of the months).”

Laus omnium mensium: Aequalis Librae September digerit horas,

Cum botruis captum rureferens leporem.

“September divides the hours in equal parts on the scales, while carrying from the country the captured hare together with clusters of grapes.”

It might seem peculiar and even strange that the personification of September would be dangling a captured lizard by a string in a metaphorically significant way. It is theorized, however that the lizard could be a symbol of struggle or strife. The god, Liber or Bacchus, (the Roman counterpart of Dionysus) is often associated with the lizard. This would also be appropriate since the autumnal Vindemial festivals, festivals that were celebrated from September 5th onward, were dedicated to Liber. The lizard’s capture could be a symbol of Liber’s triumph over the forces that might have threatened the harvest previous to the end of summer.

Sarcophagus with the Triumph of Dionysus. Many of the animals depicted had special significance in the mystery cult of Dionysus Sabazius, including the lizard hiding in the tree. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The divided hours in equal parts denote the Roman understanding of the Autumnal Equinox when the hours of the night and day would become equal in length. The mention of the hare is perhaps an introduction to the upcoming hunting season.

Although the the meanings behind this imagery are still uncertain, it is doubtless that this is a celebratory image. The end of Summer and the coming of a successful harvest are being celebrated. The cluster of grapes and the prepared pots seen beneath the figure of September seem ready to ferment the juice of those grapes.

Architectural relief plagues – vintage and pla tramp grapes. Rome 2nd half 1 c. AD. Grape Treading. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The Menologium rusticum (the ancient farmer’s almanac), attributes the fermenting of wine for October and instead characterizes September thusly:

Sol Virgine. Tutela Volcani.

Dolea picantur, poma legunt; aborum oblaqueatio.

Epulum Minervae.

This concise passage recognizes the month began with the sun in the sign of Virgo and was under the guardianship (tutela) of Volcanus (the god Vulcan). As instructions to the farmer, the passage describes the activity immediately preceding fermenting, which is, the preparation of the jars in which to put the wine next month (dolea picantur) by coating them in pitch or resin. They are also told to pick apples and to loosen the compacted soil around trees. The feasts (epulum) of Minerva are also to be held.

All this, the combination of the calendar and the almanac, marks the month of September as a joyous time between work, worry, and heat and the anticipation of imbibing on the new wine as they fully transition into the mild months of Autumn when the hunting season opens.

Sources:

Cours d’épigraphie latine. René Cagnat, E. Thorin, 1889 – Epigraphie latine.

On Roman Time: The Codex-Calendar of 354 and the Rhythms of Urban Life in Late Antiquity. (1991). Michele Renee Salzman. University of California Press.

The Allegories of the Months in Classical Art. Doro Levi. College Art Association. The Art Bulletin, Vol. 23, No. 4 (Dec., 1941), pp. 251-291

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

About the Author: Brittany Britanniae

Hello There! Please feel free to ask me anything about Latin Grammar, Syntax, or the Ancient World.