You in Ancient Rome: A Day in the Life Posted by Brittany Britanniae on Dec 15, 2016 in Roman culture, Uncategorized

Historians and Classics enthusiasts often pay close attention to the history surrounding the great and legendary figures of Ancient Roman politics, philosophy, and mythology. However, today, let us take a look at the people who made up what was one of the greatest and largest cities in human existence. After all, such a city was mostly made up of the people who received little, if any, recognition.

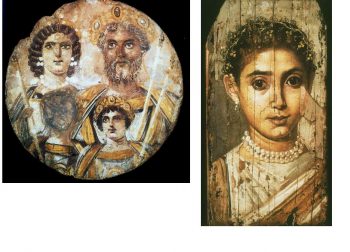

One of Gaius Fabius Pictor. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

If we were to travel back in time, the Latin we have been learning here would be handy in that case (if we can pick up the right pronunciations), our place in the Roman Empire would be shoulder to shoulder with the 50 to 90 million other citizens living their lives under the emperor’s intrigue and in accordance with the common gossip about gods and heroes. We would be one of the millions that made up around 20% of the world’s population that would live under the emperor’s rule. Like the millions we might only ever see our ruler’s face as it was minted, eternally young and handsome, on the coins we used at market.

Collection of Roman coins the Roman Museum in Augst. Author: Ad Meskens. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Not to be presumptuous, but if any of us went back it time to Ancient Rome, it would be very likely that we would live out common lives. Only very few people in the city actually experienced elite status or wealth. Even many figures from history that we respect, such as philosophers, did not enjoy extravagant or adventurous lifestyles. If we, inhabitants of the 21st century, secured a spot for ourselves in the great city of Rome, itself, we would still be one of 450,000 to just under 1 million other citizens. However, Rome was very cosmopolitan and offered a spot to people of a great variety of backgrounds. Living in Rome were Greeks, Syrians, Jews, North Africans, Spaniards, Gauls, and Britons, to name a few.

So, let’s take a trip to Ancient Rome and look at the kinds of lives we, any of us, might have led.

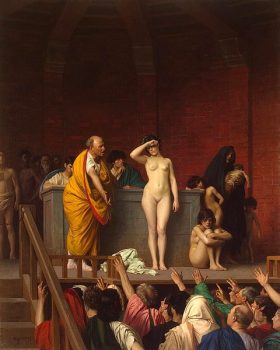

If you moved to Rome looking for work and better prospects you might have been sorely disappointed to find that most of the work in the wealthiest parts of the cities was being performed by slaves. Slaves took care of the menial tasks that the elites wanted done and so there was no money there. Slaves also performed in professions that required higher education, as well. This slimmed the job market even further since slaves also worked as teachers, doctors, surgeons, and architects. If you wanted to make money as a freed man you would need to work at a trade. You might look into being a baker, fishmonger, or carpenter. This could support you enough to stave off homelessness.

Gérome “A Slave Market in Ancient Rome”. One of Gérome’s six scenes depicting the slave-market. In this scene, naked women are presented in front of a crowd by the slave dealer. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

If you were a freed woman, you might also find work. In particular, you could work directly for the elite. You could work as a hairdresser, midwife, or dressmaker. If you lived later in the Empire you could even be a baker, pharmacist, or a shopkeeper. Women’s rights would improve over time for Rome.

Insulae, Ostia. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

If you managed to find a good job you might afford to live in the most popular housing of the city; the insulae. However, in these ramshackle dwellings you might be afraid of collapses and the fire hazards. If you live before the great fire of Emperor Nero and the fire safety precautions that followed that fire, you might want to live on the bottom floor. The bottom floors were also more spacious and comfortable and you would pay rent annually instead of monthly or weekly like the higher floors. The higher floors were colder and had little or no access to running water or sewers, the Cloaca Maximum, that the first floor enjoyed. These insulae could be as tall as 70 feet and have 5 to 7 stories; you would not covet the family that inhabited the 7th floor.

Roman insulae in Ostia Antica. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Speaking of families, who you were in your household hierarchy affected your life deeply. If you were to either take your whole family with you to Ancient Rome or start a family once you got there, gender and age decided what was happening in your life. If you’re male with a wife and children you would enjoy great opportunities for power over your family’s property and planning their future. If you were a daughter of a wealthy family in this time you would most likely be married off, strategically, between the ages of 12 and 14. The poorer you were, however, the less likely you were to be married off for alliances and you could marry later, around the cusp of 20, since your marriage would not be so important. So that is a plus.

If you were a son you would also live under your father’s rule, your property belonging to him, only until he passed away. Sons and daughters would learn Greek and Latin and receive education from slaves or nurses. In other cases, a boy from the age of 7 upward might meet with others to learn on a rooftop. Wax-covered boards to take notes on were expensive, so if you were from a lower class you might need to simply draw in the sand. You would also bring your lunch with you; a loaf of bread.

You’d enjoy this education if you, as a child, were not sold off as a slave because you were not favored by your parents. A child’s life in Rome was not always a safe one.

A day consisted of waking up and eating a light breakfast that could be made by slaves or by children or by yourself, depending on your class. If you worked you would then pack up and, much like today, go to work for the day. The wealthier you were the less you worked, but most Romans enjoyed a 6 hour business day. They would start at dawn and go home for leisure time at noon. It would probably not be an exaggeration to say that this is one aspect many of us might actually enjoy about living in Ancient Rome.

If you did not work you could manage the household and leave the house to run errands. This was usually to pick up food for the day from markets or street carts since there was no refrigeration. The poor, of the upper floors, would also go to the public fountains to collect water for meals since they could not afford wine.

If you were a woman, such as a wife who did not work, you could only go to the baths, the theater, or the games in the later years of the Empire. Be careful when walkign the streets, however, they were covered in human refuse or there were no street lights because of the high crime rate at night so it was best to get your business done before sundown. Everyone would come back to the household for dinner. Somewhat safe, at least from the crime outside but not from the infrastructure of your insulae, families enjoyed (although not always together since women would only be invited to sit with husbands as dinner in the later year) the biggest meal of the day. This meal was gruel or cereals for the poor, who were malnourished, or breads, vegetables, and olive oil for the middle classes. Meat was tough to come by at a cheap price unless a sacrifice had just been held.

All in all, you can probably see now why the Ancient Roman had so many festivals and observed them so diligently year to year. Any chance for indulgence and extravagance would be warmly welcomed by the hard-pressed masses who saw very little of the elites and rulers. It is also clear now why emperors would give them “bread and circuses” as a means of appeasing the citizenry.

If you would like to see more about the life of average Ancient Romans I highly recommend this TED video:

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

About the Author: Brittany Britanniae

Hello There! Please feel free to ask me anything about Latin Grammar, Syntax, or the Ancient World.