Nature Words in Irish, pt. 5: Catkin to Crocus (following up on acorn to buttercup) Posted by róislín on Oct 17, 2019 in Irish Language

(le Róislín)

“Catkin” — now there’s a word I don’t use very often in English and I’m tickled pink to be writing about it here, in a blog for Irish language learners. The other “c-anna” words for today’s post are a little more basic: cauliflower, chestnut, clover, conker (not “conquer” as such!), and crocus.

Anybody remember why I’ve picked this set of words to discuss here? Going back to my post of 20 August 2019, we’ve been looking at the 50 or so nature terms that were removed from the Oxford Junior Dictionary (OJD), which I must add is otherwise a very admirable publication, as is everything thing I’ve ever seen from Oxford University Press. I especially love the dictionaries (ní nach ionadh, má tá aithne agat orm!). I still treasure my 2-volume miniaturized edition, which came in its own specially designed box with a drawer for the magnifying glass that was included. Pre-online databases, of course, which is where most people, including myself, use the Oxford English Dictionary today, given that the last printed volume took up four feet of shelf-space (1.22 m) and weighed about 150 pounds (over 10 stone) .

The publishers justified the removal of the nature terms from the OJD in order for make room for new, high-tech, social media-oriented words like “broadband” and “chatroom.” Since the OJD has a word ceiling of 10,000, some older words had to go to make room for the new. Articles about the removal started to appear about 10 years ago and have surfaced intermittently since then, especially as the dialogue about the role of nature in our lives, especially children’s lives, continues. Does it make us happier, healthier, more grounded, and perhaps less allergic, to spend more time in nature, looking at and interacting with 3-dimensional objects in the landscape? That’s one important question, but I also wonder what the Irish reaction would have been if something similar had happened with an Irish language dictionary. Not that there are lots of monolingual Irish dictionaries around (though An Foclóir Beag meets that challenge nobly). This is especially true regarding children’s dictionaries, but there are, at least, school dictionaries, picture dictionaries, etc. An Foclóir Beag is great, but it’s meant for the adult reader, or at least the older child. The OJD‘s target readership was seven-year-olds.

Be all that as it may, in this blog series, we’ve been working our way through the Irish versions of those same 50 nature words and pondering what lucht labhartha na Gaeilge would think if the same words were removed from any of the foclóirí Gaeilge. That said, let’s get down to “smior an scéil,” that is to say, i mBéarla, the brass tacks or the nitty gritty. There are so many terms for today’s blogpost (na c-anna), that we limit this listing to the singular and plural forms of the words. Maybe at some point in the future, we can add more forms for possessive, etc:

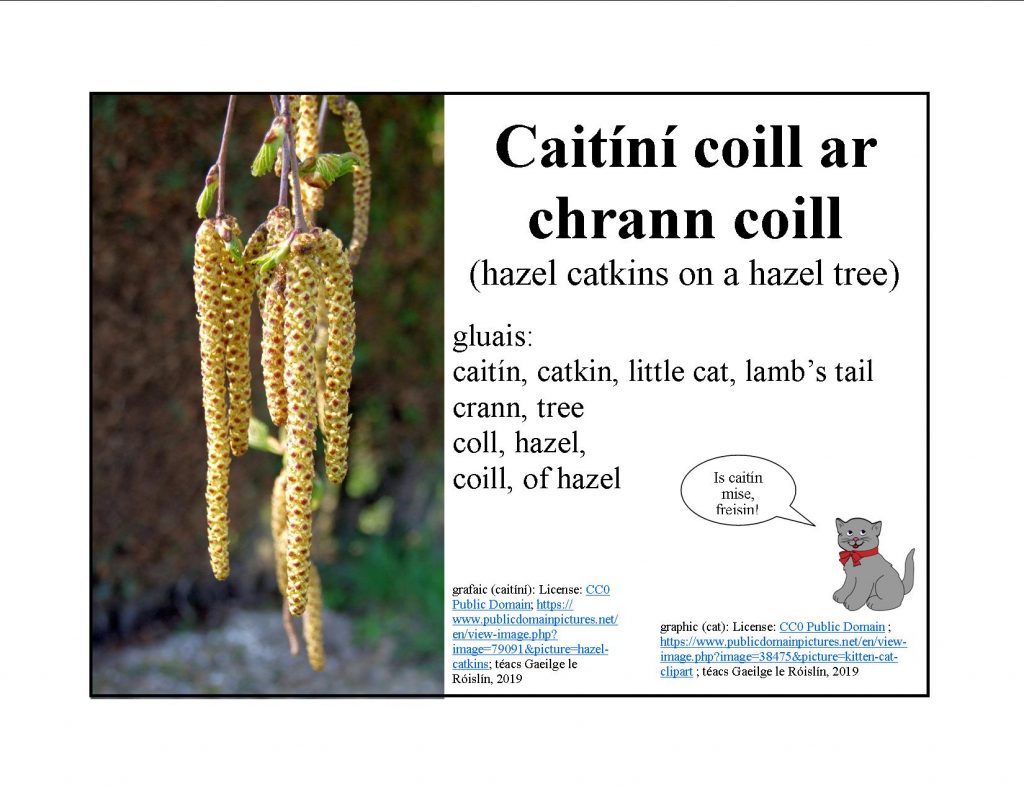

1)) catkin (aka lamb’s tail): caitín coill (lit. little cat of hazel), pl. caitíní coill OR caitín sailí (lit. little cat of willow), pl. caitíní sailí. And let’s not forget that Irish has a specific word for “catkin-bearing” (important when discussing plant breeding and propagation): caitíneach. It also means “napped” in fabric. Catkins can be seen particular on willow or hazel trees, and also on birch, hickory, sweet chestnut, and sweetfern

2)) cauliflower: cóilis, pl. cóiliseacha

3)) chestnut: castán is the most general term, pl. castáin. There are also different types, like castán Eorpach (sweet chestnut) and cnó capaill (lit. nut of horse or as in English, horse chestnut) and castán uisce (water chestnut).. There are , of course, all of those “old chestnuts” but that’s a completely different word in Irish, more straightforward actually: seanscéal, and if it’s a really really old chestnut it could be a “seanscéal agus meirg air” (meirg = rust). An interesting related term is “castainéid” (castanets), from the Latin “castanea” (chestnut) via the Spanish “castaña,” “castañeta,” and “castañuela” (hmm, three Spanish words for castanets? Or are they for chestnuts, as such. Pé scéal é — suimiúil!

4)) clover: seamair, pl. seamra (as a subject) and seamar (sa tuiseal ginideach, iolra, included here despite our attempt to trim down the entries b/c it’s such an unusual plural). This word gives us “seamróg” (shamrock), which is basically a type of clover, the exact variety of which is often debated, and gets discussed every Lá ‘le Pádraig (St. Patrick’s Day). I definitely could not imagine removing this word from an Irish language dictionary!

And let’s not forget the adjective: seamrach, which, not surprisingly, means “covered with clover” as slightly differentiated from “seamrógach” (covered with shamrocks).

5)) conker: this brings us back to “chestnut,” specifically “cnó capaill,” with “cnó” being the Irish for “nut” and “capaill” (of horse). So, in Irish it’s not related to “conquer,” for which the Irish would be “buaigh” or “bain amach” or “cloígh.” That said, William the Conqueror is referred to as “Uilliam Concaire.” Hmm, again, suimiúil. Something tells me that in this high-tech age, “conkers” as a game is not as popular as it used to be, when children made many of their own toys. So, a little reluctantly, I can see yielding this dictionary entry to “progress.” But … whoa! A little further research shows competitions and championships in Britain, Ireland, and even North America, some just having started up in recent years. So I guess the game is holding its own, even with the concerns over players’ safety and liability issues. It is interesting to note that while English distinguished between “horse-chestnut” as a general term and “conker” for the game, Irish uses one term “cnó capaill” for both the ordinary nut and the nut as prepared for playing conkers.

And finally (for the C’s in our list):

6)) crocus: the basic form is pretty easy: cróch, for the ordinary crocus flower, and there’s also “cróch an fhómhair” (autumn or autumnal crocus, aka colchicum, which is toxic) and “cróch safrón” (saffron crocus, which gives us saffron, which is edible, tasty, and expensive). “Cróch” also means “saffron” and can be used for the color, with or without “-bhuí” added (as in cróchbhuí, saffron-yellow, saffron-colored). Related terms include: “cróchadh” (dyeing fabric with saffron or flavoring food with saffron), anlann cróch (saffron sauce). rís chróch (saffron rice) and arán cróch (saffron bread). BTW, none of the sources I’ve checked list a plural form for “cróch.” Just to add to the taxonomical confusion, i m’intinn féin, ar a laghad, “cróch an fhómhair” is also used for “meadow saffron,” (Colchicum autumnale). Some sources tell me that autumn crocus and meadow saffron are the same plant, but as far as I can tell, they have different scientific names, “autumn crocus” being “Crocus nudiflorus.” Wikipedia tells me that only C. autumnale is native to Ireland and Britain, so presumably, “cróch an fhómhair” would be the plant most discussed in this family in Irish. If you’re trína chéile with this, mise freisin.

Well, that’s our nature terms list for the letter “c”. I hope you found them useful and that unlike the presumed 7-year-olds using the OJD, you’ll continue to have some reason to plant these words into your everyday “comhráite” in Irish. SGF — Róislín

Nóta: By the way, in the limited amount of time I have to explore the nature terms issue in other languages, I’ve found that Welsh has three words for “catkin” of willow/sallow (cyw gŵydd, gŵydd fach, cenau coed) and another three for hazel (the straightforward cenau cyll and the more charmingly figurative “cynffon oen bach” or “cwt oen bach,” both meaning literally “little lamb’s tail”). Given the “lamb’s tail” shape of a fully developed “catkin,” perhaps the “cynffon” or “cwt” theme could be used for other trees as well. Siaradwyr Cymraeg?

iarbhlaganna sa tsraith seo (nature words)

‘Bluebell’ or ‘Broadbrand’: Which Word Should Be in a Children’s Dictionary? — A British Example and Irish Question Posted by róislín on Aug 20, 2019 in Irish Language

Nature Words: Should They Be in a Children’s Dictionary or Not? Let’s Consider the Irish Word “dearcán” (acorn) Posted by róislín on Aug 31, 2019 in Irish Language

Nature Words: the Irish for ‘almond’ and a baker’s dozen of related terms Posted by róislín on Sep 18, 2019 in Irish Language

Nature Words in Irish, pt. 4: blackberry, budgerigar/parakeet, buttercup (and bluebell in review)Posted by róislín on Sep 30, 2019 in Irish Language

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Leave a comment: