Hacking Pronunciation in Any Language with the IPA, Part 1: Consonants Posted by Transparent Language on Feb 2, 2015 in Archived Posts

Jakob Gibbons writes about language and travel on his blog Globalect. He often shares his experiences with learning languages on the road, and teaching and learning new speech sounds is his specialty.

One of the biggest hurdles to jump in learning a new language is getting control of new speech sounds you’ve never made before. The French uvular <r>, Arabic pharyngeals, and Cantonese pitches all seem insurmountable when starting out at the base of Mt. Learnalanguage looking up. Thankfully, there’s a tool that’ll help you get to the top safe and sound: the International Phonetic Alphabet.

The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) is the tool used by linguists to describe and document every unique sound that occurs in every human language on the planet. Every word in human speech is made of a series of sounds strung seamlessly side by side: the fricative s at the beginning of the word ‘speech’, the p that explodes from your lips next, the high vowel sound depicted by the ee in the middle, and the final stopping of the tongue before sliding away for the ch sound at the end.

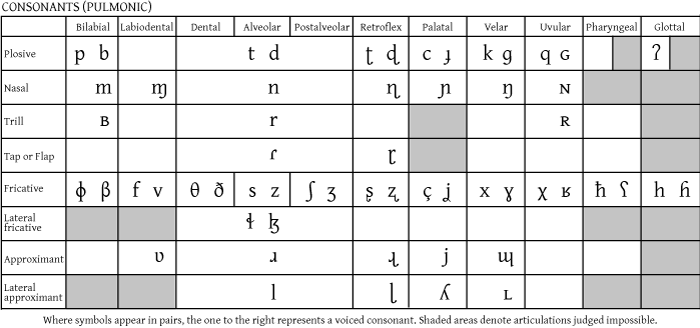

Consonant sounds are like points on a graph: they occur where two lines intersect. One axis is the place of articulation, or the parts of your vocal tract that move to produce a sound, and the second axis is the manner of articulation, or the specific way in which you pass air through the vocal tract.

When you first glance at the IPA consonant chart, it’s nearly as overwhelming as day one of learning a new language. But the hardest part is getting down these two concepts, place and manner of articulation. The rest comes naturally with a little practice.

Place of Articulation

If you look at the top of the IPA consonant chart, you’ll see a row of words that seem more appropriate for a biology exam than a foreign language lesson. From left to right, these are your places of articulation, the parts of your mouth that you must engage to make speech sounds, from front to back in the vocal tract. Some of them you can probably figure out on your own: ‘bilabial’ sounds are made with both lips (‘bi’ = 2, ‘labia’ = lips), and ‘palatal’ sounds are made with your tongue pressed against the roof of your mouth, your palat.

My hack for learning place of articulation is figuring out what you naturally do with each articulator, whether or not you use it to speak your native language. Uvular sounds are made with the uvula, the dangley punching bag in the back of your mouth that fascinated you as a six-year-old staring into your bathroom mirror. As an English speaker, I’ve never used it in speech, but I do use it to gargle water or to immitate a cat purring. Knowing that, I’m one step closer to being able to use it in speech.

Some of the names for places of articulation are intuitive, but not all. Here’s a cheat sheet for talking about some of the moving parts of your built-in language machine:

Labiodentals: Where lips meet teeth, labiodental sounds happen. This always involves the top teeth on the bottom lip, like in the English sounds /f/ and /v/. If you’re very furiously fighting the drive to give up on Farsi, you shouldn’t, because it’s got two labiodental sounds that you’ve already got down!

Dentals: Sometimes called interdental, these consonants are made with the teeth. English is notorious for its difficult dentals, represented by the IPA symbols /ð/ and /θ/ and heard in words like think, thing, with, or either. On each <th> cluster, you feel your tongue dart between your teeth and shoot back for the next sound.

Velars: These are the sounds made furthest back in the English-speaking mouth, using the velum, the little strip of skin that keeps you from drowning when you swallow a mouthful of water. This is engaged in English /k/ and /g/ like in go, big, or kick.

These are just three of the eleven places of articulation in the vocal tract. Some of them are not used at all in English – like retroflex or pharyngeal sounds – but with the IPA you can get any of them down with a bit of practice. Once you’ve found your articulators, the trick is figuring out what to do with them.

Manner of Articulation

Finding the spot where you make a /g/ doesn’t mean you suddenly know what to do with that spot. If you want to make an English /g/ sound, you need to know what a plosive is, how it’s different from a fricative or an approximant, and how to produce one from your velum. Whereas place of articulation on the IPA consonant chart moves pretty logically from front to back in the mouth, manner of articulation can be a bit more complicated. Here are some of the most common ways of moving air through your vocal tract to make a speech sound:

Plosives: Also sometimes called stops, plosives are characterized by a single burst (or explosion) of air coming out of your mouth all at once, instead of slowly or continuously. Sounds like /s/ and /th/ are not plosives; in English, plosive sounds are /p/, /b/, /t/, /d/, /k/, and /g/. Plosives burst from your mouth in words with any of these sounds, like pop, aid, cage, bird, and doing.

Fricative: A fricative consonant is made by continuously squeezing air through a tight space in your vocal tract. When you make an /s/, for example, the front of your tongue climbs up toward the alveolar ridge just behind your top teeth, but it doesn’t actually touch it. Instead, it constricts the air through this tight space, giving you the swishy, lispy sound heard in /s/, /z/, /f/, /v/, /ð/, and /θ/. The first letters of ton and son are made at the exact same place in the mouth, but where the /t/ in ton is a single quick burst of air, the /s/ in son is squeezed through an open (but tight) space.

Fricatives and plosives produce most of the sounds you’ll need in most languages. These are just two of the basic manners of articulation you can learn with the IPA. Others, like liquids and approximants, are more difficult and less concrete, but Wikipedia has some really helpful articles on these sounds, and you can find them from the Wikipedia article on the IPA.

Putting the pieces together

Learning where the places of articulation are in the vocal tract and how to produce the different manners of articulation are the most basic building blocks of learning new sounds in a new language. If you learn the IPA, you’ve got an inexhaustible tool for looking up the phonology or the speech sounds of any language. Then, when you’re struggling to figure out just exactly what a German’s mouth is doing when they say the <ch> in ich, you can turn to the IPA and find out that it’s a palatal fricative: just constrict air through a tight space between your tongue and the roof of your mouth, and you’ve got it! Wünderbar!

Often this will take a lot of practice and a lot of embarassing mispronunciations before you get it, but just learning how to practice and get better at consonants in a new language is a huge first step. In my next post for Transparent Language, I’ll go into the way more frustrating world of vowels and how to use the IPA to get them down.

Already got your plosives and approximants down? It’s time to move on to Part 2 and tackle vowel sounds!

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

Ann Crawford:

Very interesting. You make it sound so easy but I think I may find it a bit more difficult! However I must look it up and try it!

Jakob Gibbons:

@Ann Crawford Yeah Ann, actually I think it is pretty difficult at first! You kind of start from nothing, so it takes a lot of studying in the beginning, but it gets exponentially easier as you go and is totally worth the effort.

vta:

I’ve found the IPA primarily useful for representing sounds that I’ve already learned by listening and imitation.

Bluebee Majarimenna:

Well, it’s a voiceless palatal fricative when it isn’t a voiceless velar fricative or voiceless velar stop 😛