Nicole, I am your Esperanto father Posted by Chuck Smith on Jul 3, 2013 in Interview, Native speakers

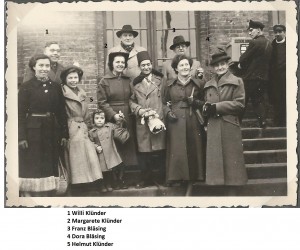

Last week we had an interview with Nicole Klünder, a third generation native Esperanto speaker. It became so popular that a Belgian radio station even picked up on it to interview a local native Esperanto speaker (in Dutch). A few days later, Nicole’s father Helmut Klünder wrote me to let me know of some factual errors in my post. So, I thought I would take this unique opportunity to sit down with someone who was not only raised as a native Esperanto speaker, but also brought one up as well!

It would make sense that you would best understand your family history related to Esperanto. It sounds like there was quite a funny story between your grandfather and father. Could you elaborate on that?

Mia patro tre favoris la klasikan latinan kaj la klasikan grekan lingvon. Krome li estis tre talenta pri matematiko. Kun mia avo li ofte amike disputis pri Esperanto. Post la milito, proksimume 1946, kiam la situacio estis malbona, mia avo promesis cigaron, se li lernus Esperanton, dum mia patro opiniis, ke tre taŭgus lerni Esperanaton, ĉar tiam li povus pli efike argumenti kontraŭ tiu artefarita lingvo. La rezulto ne estis de mia patro antaŭvidebla – unu jaron poste li ne nur estis membro de la refondita Germana Esperanto Asocio, sed membro de la konsilio.

My father really favored Classical Latin and Ancient Greek. Besides that, he was very talented in Math. He often got into arguments with my grandfather about Esperanto. After the war, around 1946, when the situation was bad, my grandfather promised him a cigar if he would learn Esperanto. That’s when my father decided that would be a great opportunity to learn Esperanto, so then he could more effectively argue against this artificial language. My father couldn’t imagine what would happen – a year later he was not only a member of the refounded German Esperanto Association, but also a member of its council.

Also, while I’m at it, what was it like growing up as a native Esperanto speaker for you?

Verdire estis por mi io tute normala. Simple estis kvazaŭ mi parolus kun kelkaj homoj laŭ iom alia maniero ol al aliaj homoj. La ideo, kio estas lingvo tute ne ekzistis en mia kapo, nur ek de tiam, kiam mi iris al gimnazio kie mi estis konfrontita kun la latina lingvo. Normalkaze mia patrino (kaj vershajne ankau mia avo) parolis Esperanton kun mi, mia patro la germanan. Kiam estis esperant-lingvaj gastoj miaj geavoj kaj miaj gepatroj parolis Esperanton.

Really, it was just normal for me. It was as if I would speak with some people a bit differently than others. The idea of language didn’t even exist in my head. Only when I started going to school was I confronted with Latin. Normally, my mother (and probably also my grandfather) spoke Esperanto with me, and I spoke German with my father. When there were Esperanto guests, my grandparents and my parents spoke Esperanto.

Miaj gepatroj atentis pri tio, ke mi havu ankau al aliaj familioj kun denaskaj Esperanto-parolantaj infanoj kontakton. Tio estis cheĥ-devena familio en Munkeno, kie mi plurfoje estis dum kelkaj monatoj gasto kaj familio Brandenburg en la apuda urbo Münster. Li pli agha de la du filoj de familio, Ulrich Brandenburg, estis dum la infanjaroj mia esperant-lingva “ĉef-amiko”. Li nun cetere estas la germana ambasadoro en Moskvo.

My parents were careful for me to also have contact with other families who had native Esperanto kids. There was a Czech family in Munich where I sometimes was a guest for a few months at a time and then there was the Brandenburg family who lived in nearby Münster (Germany). The oldest of the two sons, Ulrich Brandenburg, was my Esperanto “best friend” back in my childhood days. Interestingly enough, he is now the German Ambassador in Moscow.

Why did you decide to raise Nicole speaking Esperanto from birth? Which ways did you teach her Esperanto like your father taught you? Did you do anything differently?

Neniam estis la demando de kialo. Ni estis dulingva familio, la patrino de Nicole venis el Pollando, kun multaj internaciaj gastoj. Ni ne havis koncepton pri la maniero, kiel dulingvigi Nicole. Simple ni vivis laŭ nia dulingva maniero kaj vizitis multajn internaciajn renkontiĝojn. Nicole ne respondis al ni en Esperanto, kio iom seniluiizigis min. Kelkaj geamikoj asertis, ke Nicole ja parolas la lingvon, sed mi neniam aŭdis ŝin paroli Esperanton.

“Why” was never a question. We were just a bilingual family, Nicole’s mother comes from Poland, with many international guests. We didn’t have a concept of how to raise him bilingually. We just lived bilingually and visited many international meetings. Nicole didn’t answer me in Esperanto, which somewhat disillusioned me. Some friends asserted that Nicole does indeed speak it, but I never heard her speak Esperanto.

Mi estas mentoro ĉe la tiel nomata brazila Esperanto-kurso. Iutage mi eksciis, ke alia amiko de mi ankaŭ estas mentoro. Mi ekscivolemis kaj petis la kompletan liston de mentoroj. Kaj je mia granda surprizo aperis sur ĝi mia 12-jara filino. 🙂

I am a mentor of the so-called Brazilian Esperanto course. One day I learned that another friend of mine is also a mentor there. I was curious and asked for the complete mentor list. To my great surprise, I found my 12-year-old daughter on that list. 🙂

Given this unique viewpoint on Esperanto history, how have you seen the Esperanto community change over the generations? How were you and your family active in the movement?

La uzo de Esperanto en la generacio de mia avo estis grandparte skriba. Mia avo partoprenis nur unu internacian renkontiĝon, nome la faman nurembergan Universalan Kongreson en la jaro 1923. Li vojaĝis kun du valizplenoj da mono (estis la inflacia tempo), sed la mono rapide elcherpiĝis kaj li devis pro monmanko reveturi antaŭ la fino de la UK. Personajn kontaktojn mia avo havis en Nederlando, kiuj ofte invitis lin post la 2-a mondmilito kaj li havis en Nederlando enspezon per muziko (origine mia avo estis profesia muzikisto ĉe la prusa armeo.) Ĝis la morto mia avo havis viglan korespondadon precipe kun kelkaj nederlandanoj.

The Esperanto in my grandfather’s generation was mostly written. He participated only once in an international meeting, namely the famous Nuremberg Universal Congress in 1923. He travelled with two suitcases full of money (due to hyperinflation in Germany, paper bills were worth so little that people had to carry them in bulk). Unfortunately, the money quickly ran out and he had to return home before the end of the congress. He had personal contacts in the Netherlands; he was often invited there after World War II where he earned money playing music. Originally, he was a professional musician for the Prussian army. Until the end of his life, he had a lively correspondence, with Dutch friends mostly.

La posta Esperanto-generacio estis multe pli vojaĝema, vojaĝoj eksterlanden estis pli facilaj kaj ŝajne ankaŭ malpli kostaj ol antaŭe.

The next Esperanto generation was much more likely to travel. Travelling abroad became much easier and much more affordable.

Nun estas denove alia periodo. La Universalaj Kongresoj kaj TEJO-Kongresoj perdis iom da ilia signifo, ĉar en multaj landoj ekfloris aliaj, malpli grandaj internaciaj aranĝoj, kiuj estiĝis parte tre popularoj. En Germanio ni komencis dum la fino de la 50-aj jaroj kun la Internacia Seminario, dum la 80-aj jaroj aldoniĝis la Internacia Festivalo kaj poste sekvis la Novjara Renkontiĝo. Tiuj tri aranĝoj okazis ĉiuj samtempe kaj en ekstrema kazo altiris sume 700 partoprenantoj. Krome en Germanio ni ankaŭ havas la paskan renkontiĝon Printempa Semajno Internacia (PSI), kie la nombro da partoprenantoj varias inter 100 kaj 200. Laŭ mi momente la aktivado en la reto ankaŭ logas multajn personojn.

Now is another period again. The Universal Congresses and Youth Congresses have lost some of their meaning, because many countries have spawned their own smaller international events, some of which became very popular. In Germany, we started in the end of the 50’s with Internacia Seminario (IS) a New Year’s event, and then the Internacia Festivalo (IF) sprang up in the 80’s. Later, the Novjara Renkontiĝo (NR) joined the bunch. These three events all happening around New Year’s have sometimes attracted 700 participants in total. [To learn more about the history of Esperanto New Year’s events, please see Celebrate the New Year, Esperanto style!.] Besides that, we also have an Easter event in Germany called the Plentempa Semajno Internacia (PSI) with 100-200 participants each year. I believe online activity also attracts many people.

Mia rolo en la E-movado estas por denaskulo nenormala. Kiel Nicole jam prave menciis, ĉe denaskuloj mankas en ilia vivo la konscia decido lerni Esperanto kaj ankaŭ ne la necesa konvinko. Mi ĉiam komparas tion kun la germana lingvo, kie mi ja ankaŭ ne membras en asocio por propagandi la lingvon internaciskale. Ke mi en 1967 transprenis taskon en GEJ estis pli hazarde ol intence – la siatempa prezidanto de GEJ loĝis en Münster kaj mi kutime vidis lin unufoje monate. 1969/70 mi surprize elektiĝis prezidanto de GEJ sen ia antaŭa estrarlabora sperto. GEJ tamen travivis tion. Dum 5 jaroj mi estis prezidanto, tempo dum kiu okazis la IJK en Münster en 1974. Verŝajne jam ĉe la plejmulto forgesita estis la instalo de elektronika administrado, esence membrolisto, sur la komputilo de la universitato en Münster. Estis modesta “datumbazeto” sur trukartoj. Dum tiu tempo mi ankaŭ estis en la estraro de GEA, kiel reprezentanto de la junularo.

My role as a native speaker in the Esperanto movement isn’t normal. Like Nicole already mentioned, natives never consciously decide to learn Esperanto and also don’t have the necessary conviction. I always compare that to German, in which I’ve also never been a member in an association to promote the language on an international level. The fact that I took over a task for GEJ (Germana Esperanto Junularo) in 1967 was more random than intentional – the president of GEJ at the time lived in Münster and I typically saw him once a month. 1969/70 I was surprised to discover that I was elected its president without any former board experience. However, GEJ survived that. In the five years in which I was president was the time when the International Youth Congress of Esperanto took place in Münster in 1974. Probably most people have forgotten when we installed electronic administration, essentially a member list, on Münster University’s computer. It was a modest “little database” on punchcards. During this time I was also on the GEA board as their youth representative.

Fine de 1976 mi forlasis la estraron de GEJ, kaj transprenis aliajn taskojn en la estraro de GEA. En 1983 mi elektiĝis prezidanto de GEA kun multe pli juna estraro, la mezuma aĝo de la estraranoj estis sub 40 jaroj. Dum “mia epoko” mi fondis PSI kaj IF, ĉar ni sentis, ke necesas pli da internaciaj aranĝoj. En 1989 mi forlasis la estraron de GEA, ĉar mi sentis min post 19 jaroj iom forbrulita kaj ankaŭ mia profesio necesigis min, dediĉi min pli tie. Mi kompreneble restis fidela vizitanto de la aranĝoj. De 1998 – ankaŭ pli hazarde ol planite – mi enkadre de PSI organizis la “knajpon” [Chuck: slango por trinkejo], ĉar en la junularaj domoj la bufedo flanke de la domo ne bone funkciis.

At the end of 1976 I left the GEJ board, and took over other tasks in the GEA board. In 1983, I was elected president of GEA with a much younger board; the average board member’s age was less than 40 years old. During “my epoch” I founded PSI and IF, because we felt that there needed to be more international meetings. In 1989 I left the GEA board, because I felt burnt out after 19 years and my profession also needed me to dedicate myself more there. I, of course, kept faithfully attending events. Since 1998 – also more randomly than planned – I organized the bar at PSI, because the buffet didn’t work well in the youth hostels.

What do you see as the future of Esperanto?

Malfacila demando. La fakto, ke Esperanto travivis 125 jarojn kaj el skribtabla projekto estiĝis vivanta lingvo, kuraghigas. Bedaurinde estas problemo, ne nur che la E-movado, ke la homoj ne plu shatas organizighi. Mi vidas tion bone en mia urbeto, kie multaj klubetoj batalegas por resti vivantaj, ofte ne sukcese.

Difficult question. The fact that Esperanto survived 125 years, from the writing board to a living language, is encouraging. Unfortunately, there is the problem, not only in the Esperanto movement, but generally, that people don’t like to organize themselves anymore. I really see that in my city, where many small clubs are struggling to stay alive, often unsuccessfully.

Mi fine malkaŝu unu fantazian deziron de mi. Mi tre ĝojus, se oni sukcesus fondi internacan lernejon, kie la instrulingvo estas kompreneble Esperanto, kien povus veni E-parolantaj infanoj dum unu jaro. La lernejo devus funkcii konforme al la instruplano de la lando, kie ĝi troviĝas, kaj devas esti plene agnoskata, tiel ke infanoj povus iri tien dum unu jaro sen perdi en sia lando unu lernejan jaron.

Let me share a fantasy of mine. I would be ecstatic if someone would successfully found an international school where the language of instruction would, of course, be Esperanto. There Esperanto-speaking kids could go for a year. The school would need to conform to the national curriculum and be officially recognized, so that these children could go there for a year without losing a school year in their home countries.

Thank you for your very interesting and unusual perspective on the Esperanto community! Readers, do you have any questions for Helmut?

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

About the Author: Chuck Smith

I was born in the US, but Esperanto has led me all over the world. I started teaching myself Esperanto on a whim in 2001, not knowing how it would change my life. The timing couldn’t have been better; around that same time I discovered Wikipedia in it’s very early stages and launched the Esperanto version. When I decided to backpack through Europe, I found Esperanto speakers to host me. These connections led me to the Esperanto Youth Organization in Rotterdam, where I worked for a year, using Esperanto as my primary language. Though in recent years I’ve moved on to other endeavors like iOS development, I remain deeply engrained in the Esperanto community, and love keeping you informed of the latest news. The best thing that came from learning Esperanto has been the opportunity to connect with fellow speakers around the globe, so feel free to join in the conversation with a comment! I am now the founder and CTO of the social app Amikumu.

Comments:

Malaeĥio:

la oni plej grava tion mi faris estis vojaĝi eksterlanden kaj studi. Mi bedaûro ne havas ajn scion de esperanton tiam. Tiu faris ne tamen malpliigi la sperto. Iru junan viron…vidu la mondo…kaj kresku!

Haengcho:

Jes, tiu rakonto memorigas min pri miaj fruaj Esperantaj jaroj. Kiam ni (mi, la edzino kaj fileto) alvenis al Aûstralio, mia filo havis grandan problemon lernante la Anglan en lia lernejo, ĉar kvankam li povis iomete paroli kaj aûdkompreni, li ne povis legi angle. Per Esperanto mi povis helpi al li legi kaj elparoli la novajn strangajn vortojn, ĉar la instruistoj tute ne povis paroli la Germanan, kaj plue ne povis ekspliki al li kiel ekkoni la sonojn kune kun la formoj de vortoj. Post unu-du monatoj li povis legi mallongajn vortojn, kaj post ses monatoj li jam ne bezonis helpon. Nun li parolas angle, germane, esperante kaj ĉine. Bedaûrinde li ne plu uzas Esperanton ĉiutage, sed ankoraû komprenas ĝin, kiam mi parolas al vi aû ni aûskultas filmon per Youtube 😉