Dogs in India Posted by Rachael on May 1, 2019 in Hindi Language

In some parts of the world, the sight of people doting fondly over their pet dogs (पालतू कुत्ता/paaltoo kuttaa=singular, कुत्ते/kutte=plural) is extremely commonplace. But, this cultural practice of keeping domesticated dogs and other animals for no purpose other than to look cute and provide companionship is by no means a universal phenomenon. In India, for example, the average visitor will see a multitude of dogs – but most of them will be strays (आवारा/aavaara, बेघर/beghar=homeless, छुट्टा/chutthaa, or सड़क के कुत्ते/sarak ke kutte=street dogs). Although middle to upper class Indians sometimes keep dogs as pets, this practice is still not as common as it is in the United States and other Western nations. While visiting India as a foreign tourist, you’ll encounter a lot of dogs and a lot of different attitudes (रवैया/ravaiyaa) toward dogs, which I’ll discuss in some detail below.

In the city of Jaipur (in the Northwestern state of Rajasthan), where I lived, stray dogs were a common sight; in fact, India has one of the largest populations (आबादी/aabaadi) of stray dogs worldwide, numbering about 25 million. These dogs are generally very afraid of humans (इंसानों से डर लगता है/insaano se dar lagta hai) and try their best to avoid them. I also noticed that most of these dogs seemed to suffer from a variety of ailments (बीमारी/beemaari), and a few were rabid (रेबीज़ से पीड़ित/rabies se peerit) and thus very aggressive. This is something to be aware of as a tourist or visitor, especially when you are from a country where domesticated dogs are commonplace: if you see wild, stray dogs roaming in packs or alone, visibly attempting to avoid human contact, it is a strong signal that you, too, should avoid contact with them and resist the urge to treat them as you would domesticated dogs back home.

The blame for aggressive or unfriendly behavior, of course, cannot be laid entirely at the feet of these dogs, however, as they have adapted to a harsh way of life and widespread attitudes that are adversely biased against them. In many areas in India, including Rajasthan, people regard dogs as unclean (गंदा/gandaa=dirty, अशुद्ध/ashuddh=impure) creatures and nuisances that should remain outside. As I witnessed, even puppies begging for food in a Rajasthani village might be met with a physical threat as people do not find such begging “cute”; on the contrary, they see it as offensive and want the dog to maintain its distance. And part of this distance between canine and human is simple common sense: every year, 36% of the rabies deaths in the world occur in India, most commonly from dog bites. Rabies runs rampant in stray dog populations there and it is usually the elderly, the poor and children who are easy victims (शिकार/shikaar) of rabies-induced, aggressive dog behavior. Unfortunately, India has struggled to control the spread of rabies because the preventative measure of sterilizing stray dogs requires vast resources, including money, and a consistent and organized approach that few cities or regions have the ability to implement, especially as the amount of trash (कचड़ा/kachraa) left in city streets only encourages dog populations to flourish.

With that being said, you will come across quite a few pet dogs, even in smaller cities like Jaipur, although they tend to be foreign breeds (विदेशी नसल/videshi nasal or किस्म/kism=kind, type) such as golden retrievers and pomeranians. My host father in Jaipur used to love bragging about his old dog, a golden retriever who had passed away, saying that he was the king of the neighborhood (पड़ोस/paros) and could command the respect of even the street dogs that roamed the by lanes. Sadly, very few people want to adopt this “Desi dog,” (देसी कुत्ता, देसी/desi=native) Indian pariah dog or pye-dog, as it is variously known, which is the most commonly found dog breed in India. Despite their “unpopularity,” this dog has many factors working in its favor: it has evolved due to natural selection (rather than breeding, which can result in illnesses and other genetic weaknesses) to produce the most well-adapted genetic stock, can be easily trained and is highly intelligent and protective.

On the opposite end of the spectrum are Indian cultures in which the dog is treasured and even revered. In the town of Dharmshala (home to the Dalai Lama), for example, people feed street dogs regularly, play with them and pet them – in fact, they treat them so well that these dogs almost have the appearance of domesticated animals. Similarly, in West Bengal, people often treat street dogs with affection and care – restaurant owners frequently throw out unused food so that the stray dogs have something to eat at night and you may see a passerby cleaning the eyes of a dog playing in the lane.

In fact, a festival (त्यौहार/tyauhaar) known as Tihar/तिहार (also called Deepavali or the festival of lights known as Diwali throughout much of North India), which is commonly observed in Nepal, Sikkim, Assam and the Darjeeling district of West Bengal, features one day on which dogs are honored with a tilak (तिलक, a mark made on the forehead with vermillion or सिंदूर), a garland of marigolds (गेंदों की माला, हार/gendon ki maalaa or haar) and a special meal in celebration of the close and loving relationship that can exist between humans and dogs. To this day, one of my fondest memories of Kolkata is an angel-faced street dog that would greet me every day on my walk from home to school and back, hoping to beg a biscuit from me. The difference between these dogs and the strays in Rajasthan is like night and day: the street dogs in Kolkata, especially in the wealthier areas where people freely give of their leftover food, are friendly and instinctively trusting of people, which demonstrates just how drastically canine behavior can improve for the better when harmony exists between themselves and their human neighbors.

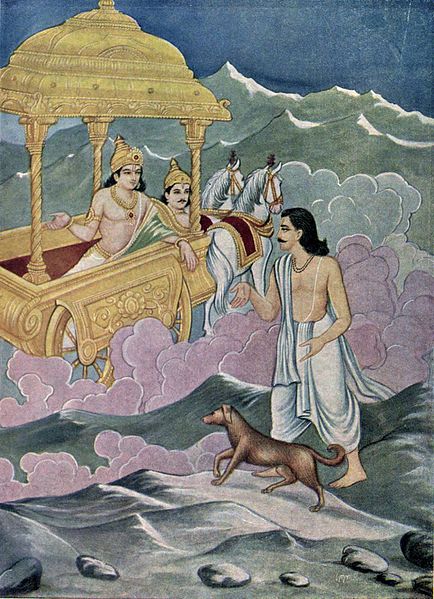

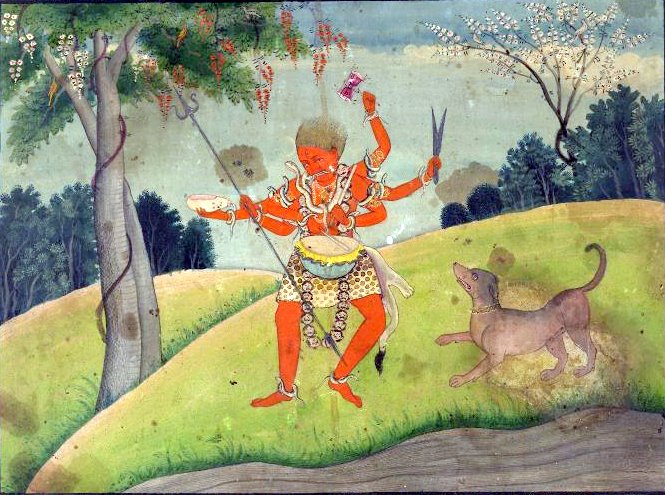

Although you will find differing attitudes regarding dogs depending on where you are in India, it is a common practice within Hinduism generally and indeed one of the essential tasks of a Hindu householder to offer food and/or drink to animals that dwell outside the home. This daily offering may take the form of a bowl of seed placed on a parapet for birds to peck at, or a dish of water for a stray dog on a boiling summer’s day. In some way, this act is not only an expression of “अहिंसा” or the nonviolent acceptance of other living beings, but perhaps also a recognition of the roles dogs have played in Hinduism over the ages: as loyal companions, such as the वाहन/vaahan or vehicle that accompanies Bhairava or a malevolent अवतार/avatar of Shiva; as fierce guardians of protected places, such as the dogs that guard the gates of hell or यम-लोक; and as faithful friends, such as the dog that followed Yudhishthir, one of the Pandava clan of the Mahabharat, into heaven (स्वर्ग), never leaving his side for a moment.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.