Indian Elections Posted by Rachael on Apr 21, 2019 in Hindi Language

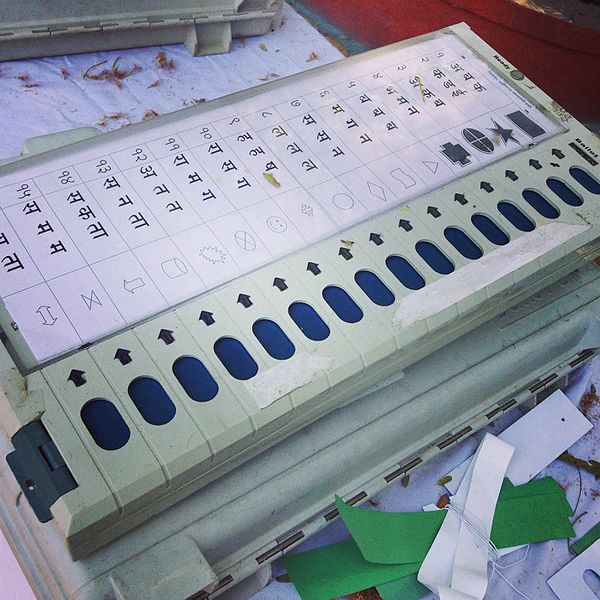

As of April 11, voting in the world’s largest democracy (लोकतंत्र/loktantra or जनतंत्र/jantantra) has officially begun. The next prime minister of India will be determined by which party or group of parties receives the most votes in forming the new parliament (संसद/sansad) (or लोक सभा/Council of the People or lower house, whose members are directly elected, unlike the राज्य सभा/Council of States or upper house whose members are elected by the lower house); subsequently, these new parliamentary members will vote on the candidate (उम्मीदवार/ummeedvaar) to become the next prime minister (प्रधान मंत्री/pradhaan mantri). As Indians head to the polls in massive numbers (about 900 million are eligible to vote) over the next five weeks, they will be voting with a number of concerns foremost in their minds: distressing unemployment levels, deepening distrust and animosity between different caste and religious groups (जाति के और धार्मिक समूह/jaati ke aur dhaarmik samooh), a lack of stable and profitable work available in rural areas and increasingly strained relations with their neighbor to the north, Pakistan. In this blog, I’ll go into some detail regarding the two main candidates for the office of prime minister and a bit of background on the issues facing Indian society (भारतीय/इंडियन, हिंदुस्तानी समाज/bhaaratiya/Indian/Hindustani samaaj) today.

The current prime minister, Narendra Modi (नरेंद्र मोदी), is running for a second five-year term this election season. His party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (भारतीय जनता पार्टी) or BJP, is the largest party (राजनीतिक दल/raajneetik dal, dal/दल=political party only) in India and advocates a Hindu Nationalist perspective that they argue should be India’s defining attribute and should be inculcated in the young, namely through school textbooks, among other media. However, some argue that this perspective can run the risk of ignoring and even stoking ill feelings toward India’s many religious minorities, such as its sizable Muslim population that makes up about 15% of the country’s citizens. On the opposing side is the Indian National Congress (भारतीय राष्ट्रीय कांग्रेस), which has billed itself as a party that champions minority rights yet, at the same time, is careful not to seem too “pro-minority” for fear that this will alienate the Hindu majority in India. Many Indians were fed up with the Indian National Congress due to decades’ worth of corruption (भ्रष्टाचार/bhrashtaachaar), and they expressed as much in the last election (चुनाव/chunaav) when Modi was overwhelmingly supported in his bid for power.

Modi partially owed his success (सफ़लता/safaltaa) to his strategy of branding himself as the antidote to the Congress Party’s endemic problems by promising to root out all corruption and focus on building India’s economic prosperity (आर्थिक समृद्धि/aarthik samriddhi). Fatigue with the Indian National Congress provided another reason for Indians to turn to the BJP in the last election as the Congress Party remained in power for much of India’s post-independence history (आज़ादी के बाद वाला इतहिास/aazaadi ke baad vaalaa itihaas). Unlike the BJP, the Congress Party bills itself as secular (लौकिक/laukik), left of center and a champion of lower castes, Dalits and religious minorities, although the Party has also been criticized as elitist and nepotistic. Rahul Gandhi (राहुल गांधी), who hails from a family of former prime ministers, is the candidate running for this office on the Congress Party’s bill. Besides these two major parties, there are also a dizzying array of other parties, including five national parties, 26 state parties and over 2,000 smaller political parties.

This election is significant (महत्त्वपूर्ण/mehettvapoorn or अहम/ahem) not just for its overwhelming voter engagement (almost 70% in the last election), which would be the envy of many democracies around the world, but because India has become a nation to be reckoned with on the global stage. Experts posit that India will soon surpass China in population size (its current population/आबादी/aabaadi is 1.3 billion) around 2024, its economy (अर्थव्यवस्था/arthvyavasthaa) has been growing steadily for many years and it is a strategic ally to the United States, both because of its proximity to China and its positive relations with Russia. Yet, India’s huge population and economic growth are at odds with the fact that most Indians are still employed in informal sectors that pay very little and offer workers almost no rights (अधिकार/adhikaar); in fact, the average Indian makes only about 5 dollars a day, which is comparable to developing countries in sub-Saharan Africa. As such, India suffers from a lack of sufficient professional employment that will satisfy its young and highly educated population (over 1/2 of India’s population is under 25).

A majority of Indian voters cast their ballots with caste or religion in mind, but even those factors are unpredictable as Indian voters are renowned for switching parties from election to election and rejecting incumbents. Besides these characteristics of voters as a whole, it is important to note the always-present yet quickly deepening divisions between urban (शहरी/shehri) and rural (ग्रामीण नाग्रिक/graamin naagrik) citizens in India today. Much of India’s population still depends greatly on income earned from agriculture (कृषि/krishee), but many farmers (किसान/kisaan) in India are facing crisis after crisis as the government (सरकार/sarkaar) has reneged on countless promises to provide subsidies for their crops (फ़सल/fasal). This lack of government support in a depressed agricultural market has driven many farmers to suicide as they face mounting debt from loans they are unable to repay. Meanwhile, urbanites face a whole host of different issues in their everyday lives, from worsening pollution (प्रदूषण/pradooshan) and high unemployment (बेरोज़गार/berozgaar) to overwhelmed roads and subways that are sorely in need of expansion and renovation. Interestingly, “megacities” like New Delhi and Mumbai boast more than 20 million residents (निवासी/nivaasee), yet this is not very representative of India’s population as a whole, 3/4 of which still resides in rural areas.

It is due in large part to these rural voters that the BJP and Modi were vaulted to power in 2014 as studies indicate that more than 60% of BJP votes were cast by rural voters. Yet, Modi has failed to delivery on many of his promises (वादा/vaadaa) to these rural voters, who counted on the government to provide them with subsidies as their farm-based incomes failed to rise and droughts (सूखा/sookhaa) destroyed their crops. Capitalizing on the public’s perception of this as a BJP failure, the Congress Party promised a basic family income (आमदनी/aamdani) of 1,000 dollars a year to families across India.

While recent polls have hinted that the Congress Party may have some success in obtaining parliamentary seats this election season, it may not be enough to oust the BJP and Modi from power. The reason for this is that the coalition formed by the BJP and other parties may be enough to hold onto Modi’s position for another 5 years. As you are following the election coverage, keep in mind that the winning party must obtain 272 seats in parliament, which will secure its power for the next 5 years as well as its ability to vote in the next prime minister.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.