Mahadevi Varma, Revisited Posted by Rachael on Jan 8, 2018 in Hindi Language, Uncategorized

जैसे आप लोगों को शायद याद है, कई महीनों पहले मैंने महादेवी वर्मा, एक बहुत मशहूर भारतीय लेखिका और कवि, के बारे में पोस्ट लिखा था (आप लोग इसे पढ़ सकते हैं, यहाँ) । लेकिन, महादेवी जी इतनी मशहूर हैं और इतने अच्छे तरीके से लिखती हैं कि एक ही ब्लॉग का पोस्ट उनके लिए काफ़ी नहीं है । इसलिए, मैंने आज आप लोगों के लिए एक नया पोस्ट लिखा है जो इस लेखिका की एक किताब के बारें में है, जिसका नाम “अतीत के चलचित्र” (Glimpses of the Past) है । अगर आप लोगों ने महादेवी जी की कविताएँ पढ़ी हों, तो आप लोगों ने ज़रूर नोटिस किया होगा कि महादेवी के गद्य और पद्य में बहुत फ़र्क है । महादेवी जी अक्सर कहती थीं कि गद्य सामाजिक मुद्दे और राजनीतिक विषय जैसी चीज़ों के लिए ज़्यादा उचित है, जबकि पद्य प्यार, अलग अलग भावनाओं और ज़िंदगी की अनगिनत रहस्यों के बारे में हो सकता है । इसलिये, महादेवी के गद्य और पद्य अलग अलग विषयों के बारे में हैं और अलग अलग ढंग में लिखा गया है ।

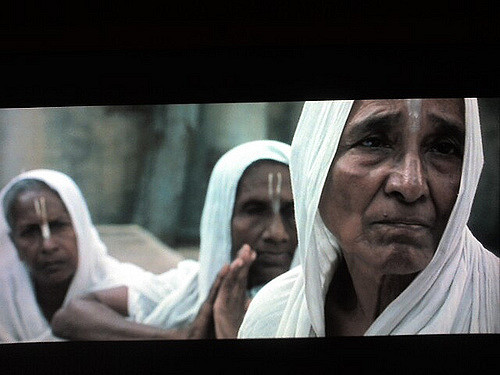

महादेवी जी की किताब, “अतीत के चलचित्र,” से मैंने एक कहानी का अनुवाद किया है । इस किताब में, महादेवी जी ने अपने बचपन के अलग अलग चरित्रओं की बहुत सारी स्मृति की चित्राएँ खींच लीं । तो हम कह सकते हैं कि यह किताब आत्मकथात्मक (autobiographical) है लेकिन, फ़िर भी साफ़ है कि शायद कुछ ब्योरे ज़्यादा “साहित्यिक” (literary) हैं । जैसे मैंने पिछली बार “बाल श्रम” के बारे में पोस्ट लिखा, यह पोस्ट एक और मुद्दे पर है जो बच्चों से संबंधित है : बाल विधवा । पुराने ज़माने में, यह बहुत आम बात थी (और कभी कभी आजकल भी होती है हालाँकि ग़ैर-कानूनी है) कि बूढ़े आदमी बहुत जवान लड़कियों से शादी करते थे क्योंकि लोग सोचते थे कि खूब जवान लड़कियाँ ज़्यादा “शुद्ध” (या “chaste”) हैं और ज़्यादा बच्चों को जन्म देंगी । लेकिन, इसकी एक बुरी बात यह है कि बूढ़े आदमी अक्सर अपनी बहुत जवान बीवियों से बहुत पहले मर जाते थे । अपने शौहर के मृत्यू के बाद, कुछ औरतों को हमेशा के लिए विधवा रहना पड़ता था, खासकर के जब ये औरतें ऊँची जाति की थीं या एक जाति की थी जो अपना पद (जाति की व्यवस्था में) सुधारना चाहती थी । इस कहानी में, मुख्य चरित्र, जिसको हुमारी कथा-वाचक (narrator) “भाभी” कहती है, वह इन औरतों जैसी है−−हालाँकि उसने जवान, हृष्ट-पुष्ट सेठ जी (tradesman) के बेटे से शादी की, फ़िर भी वह (उसका शौहर) शादी से एक साल बाद मर गया और भाभी, उन्नीस साल होने पर भी, हमेशा के लिए विवधा ही रहेगी ।

“भाभी/Bhaabhi” (“Sister-in-law”)

*More specifically, a “bhabhi” denotes an elder brother’s wife.

इतने वर्ष बीत जाने पर भी मेरी स्मृति, अतीत के दिन-प्रतिदिन गाढ़े होनेवाले धुँधलेपन में एक-एक रेखा खींचकर उस करुण-कोमल मुख को मेरे सामने अंकित ही नहीं सजीव भी कर देती है ।

Even after the passage of so many years––amidst the ever-thickening haze of the past’s day to day––my memory––drawing that kind and delicate face, line by line––not only sketches its outlines, but animates it before my eyes.

छोटे गोल मुख की तुलना में कुछ अधिक चौड़ा लगनेवाला, पर दो काली रूखी लटों से सीमित ललाट, बचपन और प्रौढ़ता को एक साथ अपने भीतर बंद कर लेने का प्रयास-सा करती हुई, लंबी बरौनियोंवाली भारी पलकें और उनकी छाया में डबडबाती हुई-सी आँखें, उस छोटे मुख के लिये भी कुछ छोटी सीधी नाक और मानो अपने ऊपर छपी हुई हँसी से विस्मित होकर कुछ खुले रहनेवाले ओठ समय के प्रवाह से फीके भर हो सके हैं, धुल नहीं सके ।

In comparison to her small, round face, her forehead seemed a bit too wide––although her fate (1) was restricted on either side by two black, dry strands of tangled hair––her eyes, as if attempting to shut inside themselves childhood and adulthood at once––with eyelids weighed down by long lashes and, in their shadow, those eyes, brimming with tears. Even for that small face, her straight nose seemed rather small––and, as if taken aback by the laughter imprinted above them, lips that remained somewhat open. With the flow of time, her face may be completely faded, but cannot be washed away.

घर के सब उजले-मैले, सहज-कठिन कामों के कारण, मलिन रेखा जाल से गुँथी और अपनी शेष लाली को कहीं छिपा रखने का प्रयत्न-सा करती हुई कहीं कोमल, कहीं कठोर हथेलियाँ, काली रेखाओं में जड़े कान्तिहीन नखों से कुछ भारी जान पड़ने वाली पतली उँगलियाँ, हाथों का बोझ संभालने में भी असमर्थ-सी दुर्बल, रूखी पर गौर बाँहें और मारवाड़ी लहँगे के भारी घेर से थकित-से, एक सहज सुकुमारता का आभास देते हुए-कुछ लंबी उँगलियों वाले दो छोटे-छोटे पैर, जिनकी एड़ियों में आँगन की मिट्टी की रेखा मटमैले महावर-सी लगती थी, भुलाए भी कैसे जा सकते हैं!

Because of all the housework she performed––tasks both clean and dirty, simple and difficult––her palms were as if entangled in a latticework of filth––soft in places, rough in others, they seemed as if attempting to hide what remained of their tenderness––compared to her lusterless nails, which were encrusted with black lines, even her thin fingers seemed a bit too heavy, they appeared helpless and weak even to support the burden of her hands––her arms, rough but fair-skinned––even wearied by the fullness of her skirt (2), her small feet, with their long, thin toes, still gave the appearance of a natural softness––those feet, whose ankles seemed as if painted with lines of earth-colored lac (3) from the dirt of the courtyard––how can such memories be forgotten!

उन हाथों ने बचपन में न जाने कितनी बार मेरे उलझे बाल सुलझा कर बड़ी कोमलता से बाँध दिये थे । वे पैर न जाने कितनी बार, अपनी सीखी हुई गंभीरता भूल कर मेरे लिये द्वार खोलने, आँगन में एक ओर से दूसरी ओर दौड़े थे । किस तरह मेरी अबोध अष्टवर्षीय बुद्धि ने उससे भाभी का संबंध जोड़ लिया था, यह अब बताना कठिन है । मेरी अनेक सहपाठिनियों के बहुत अच्छी भाभियाँ थीं; कदाचित् उन्हीं की चर्चा सुन-सुनकर मेरे मन ने, जिसने अपनी तो क्या दूर के संबंध की भी कोई भाभी ने देखी थी, एक ऐसे अभाव की सृष्टि कर ली, जिसको वह मारवाड़ी विधवा वधू दूर कर सकी ।

Who knows how many times in my childhood those hands untangled and braided my snarled hair with such tenderness. Who knows how many times those legs, forgetting their studied gravity, ran from one end of the courtyard to the other to open the door for me. It is now difficult to explain how my ignorant, eight-year-old mind attached to her the relationship of “Bhabhi.” I had many classmates who had numerous decent bhabhis; perhaps, listening to their discussions, my mind, which had never even conceived of something so remote as a “Bhabhi,” had invented this lack of one, which could only be dispelled by that widowed daughter-in-law of a Marwari (4) family.

Notes:

- “Fate”: here, I translated “ललाट/lalaat” as fate rather than its alternative meaning, forehead or brow, to give emphasis to the fact that, at least in North India, Hindus often consider one’s fate or destiny to be inscribed on one’s brow, signifying that it is in plain sight for the discerning eye to analyze and that it cannot be changed.

- “Skirt”: the original states that she wears a “मारवाड़ी लहंगा/Marwari lehengaa,” which is a type of traditional dress that involves a blouse, a dupatta or veil for modesty and a long, heavy skirt.

- “Lac”: this is a red substance that married women use to decorate their feet. It is ironic in this context as this young woman, who will forever remain a widow, has streaks of dirt on her feet that resemble the adornments married women wear, which are now forbidden to her.

- “Marwari”: refers to a caste that hails from Rajasthan (in the मारवाड़/Marwar region) and is usually wealthy and involved in some form of trade or business.

Food for Thought:

You’ll notice that I underlined certain words in the story above––why do you think Mahadevi ji used these words so often throughout her story? What significance do they have? What kind of picture do they paint of “Bhabhi” and her life as well as the perspective of the narrator?

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.