Upendranath Ashk: Rebel, Misfit, Iconoclast (Part 3) Posted by Rachael on Nov 16, 2017 in Hindi Language, Uncategorized

Namaste/नमस्ते, aadaab/आदाब/آداب, and welcome back to my blog series on the notorious Hindi-Urdu writer, Upendranath Ashk/उपेन्द्रनाथ अश्क/اپندرناتھ اشک! If you haven’t yet read parts 1 and 2, you may want to do so before delving into this third and final part.

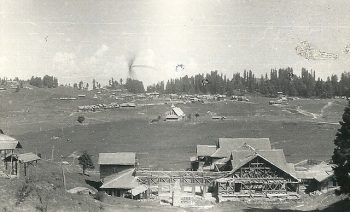

After his third marriage to fan and fellow writer, Kaushalya Devi, Ashk soon sought further stimulation and increased compensation in the world of Hindi films. In 1944, he moved to Bombay, where he wrote screenplays and dialogue for Filmistan, a production company. It was during this stint working in Hindi films that Ashk was inspired to write one of his most famous plays, Toofan se Pehle/तूफ़ान से पहले (Before the Storm), which, due to its hearty critique of communalism (or the tendency of people from the same religious, ethnic and/or cultural background to band together against those who are “different” from them), was banned by the British government as incendiary. In 1946, Ashk was diagnosed with tuberculosis and decided to receive treatment in the Bel Air Sanatorium in Panchgani a year later (a hill station in Maharashtra). During his stay there, Ashk’s semi-autobiographical tome, Girti Divare/गिरती दीवारें (Falling Walls) was published, and he composed a notable poem, “Bharghad ki beti/बरगद की बेटी” in 1947. And, luckily for us, he wrote a short story, “Mr. Ghatpande/मिस्टर घाटपांडे,” which is loosely based on his experiences in the sanatorium and is sure to put even the most serious reader in stitches.

After being discharged from the sanatorium in 1948, Ashk and his contemporary, Nirala (about whom I also wrote a blog), received the munificence of the government of Uttar Pradesh in the form of 5000 rupees each to aid them in recovering from their ill health. This allowance enabled Ashk to move to Allahabad, the hub of Hindi literary activity at the time, with his wife and son, Neelabh. Ashk remained here until his death in 1996. Once there, Kaushalya Devi started a printing press, named after her son (Neelabh Prakashan/नीलाभ प्रकाशन), with the money she received from the Indian government due to her “refugee” status (she had to move from present-day Pakistan to present-day India during partition). At this time, it was common for writers to start their own printing presses to publish their work as publishers were often untrustworthy and unethical. Ashk continued writing and rabble rousing far into his advanced years, even becoming the first Hindi playwright to be awarded the Sangeet/संगीत (Music) Natak/नाटक (Play) Akademi Award for his oeuvre of plays in 1965.

And now, enjoy the third part of Upendranath Ashk’s short story, “Daaliye/दालिये” (“The Daal Eaters”):

शाम को छह बजे के क़रीब बटोत पहुँचे । मैं बहुत थका हुआ था, एक तो रात नींद न आयी थी और दूसरे बस में जो एक-आध घंटा आँख लगती, वह लता मंगेशकर के कान काटने वाली भल्ला साहब की उन सुपुत्रियों ने चौपट कर दी थी । बस जिस होटल के सामने जाकर रुकी, उसी में रात के लिये एक कमरा मैंने तय कर लिया । दो चारपाइयाँ थीं, बरामदा था, बहुत रोशन न था, न बहुत खुला, लेकिन सुबह गर्म पानी मिल सकता था । चाय पीने या खाना खाने के लिये दूर जाने की ज़रूरत न थी, किराया भी अढ़ाई रुपया था । सो हमने तय कर लिया कि यहीं रहेंगे और चाय का आर्डर दे दिया ।

At about six in the evening, we arrived in Batot (name of a town). I was very tired: firstly, I hadn’t slept the previous night and, secondly, Bhalla Sahab’s illustrious daughters’ earsplitting Lata Mangeshkar renditions had ruined the thirty minutes to one hour I had rested my eyes in the bus. I had booked a room for the night in the same hotel in front of which the bus stopped. There were two cots and a veranda; there wasn’t much light, nor was the space very open, but you could get hot water in the morning. There was no need to go far for chai (tea) or food; also, the rate was two and a half rupees. So, we decided we would stay right here and ordered chai.

भल्ला साहब अपनी साली और बच्चियों-समेत ज़रा देर में उतरे और उन्होंने पहले पिछले होटलों में देख लेना ज़रूरी समझा । चोपड़ा साहब और उनके परिवार को भी वे साथ ले गये । हम कमरे में सामान आदि रखवाकर आधी चाय पी चुके थे, जब वे पतलून में हाथ दिये उन सबके आगे-आगे हमारे होटल की सीढ़ियाँ चढ़े । वे दोहरे शरीर के गोरे-मोटे, मँझले क़द के आदमी थे, उनके गोल-गोल, मोटे गाल, ऐसे चमकते थे जैसे वे उन पर रोज़ मक्खन की मालिश करते हों । खुले गले की कमीज़ और गहरी हरी कार्डराय की पैंट उन्होंने पहन रखी थी । यदि उनकी अधेड़ उमर की बिल्कुल पुरानी तर्ज़ की बीवी, पढ़ी-लिखी होने के बावजूद अनपढ़ दिखायी देने वाली साली और मैले, गन्दे चेहरे वाली बच्चियाँ उनके साथ न होतीं तो वे अच्छे-ख़ासे अफ़सर लगते । पर तब हिलमैन कार खरीदने की जो बात उन्होंने की थी, उसे याद कर मैंने सोचा कि नौ-दौलतिये सेठ हैं, जो स्वयं तो कुछ संस्कृत हो गये हैं, पर उनके घर वाले उसी कीचड़ में कलाबाज़ियाँ लगा रहे हैं ।

Bhalla Sahab, accompanied by his sister-in-law and little girls, disembarked a bit later. He thought it necessary to look at the hotels we had passed first. He also took Chopra Sahab and his family with him. Having gotten our luggage brought into our room, we had drunk half of our chai when he, leading the way, climbed the stairs of our hotel with his hands in his pockets. His fair-complexioned, fat body was twice the size of a normal person’s; he was of average height and his round, fat cheeks shone as if he massaged them every day with butter. He was wearing an open-necked shirt and dark green corduroy pants. If his middle-aged, completely old-fashioned wife, his seemingly uneducated yet nevertheless literate sister-in-law and his dirty, foul-looking children had not been with him, he would have looked like a well-to-do official. Remembering what he had said about buying a Hillman (a type of car), I thought that he was a nouveau-riche merchant, who was himself rather refined, but whose family were still rolling around in the same old mud.

“कहिये आर्टिस्ट साहब, आपने कहाँ कमरा लिया है?” सीढ़ियाँ चढ़ते हुए भल्ला साहब ने कहा ।

“अजी फ़िलहाल तो चाय पी रहे हैं,” मैं हँसा, “शरीर में कुछ शक्ति आये तो कमरा ढूँढें ।”

“लेकिन शाम हो रही है ।”

“और कहीं न हुआ तो यहीं पड़े रहेंगे,” मैंने थके हुए स्वर में कहा, “सामान यहीं रखवा दिया है । ऊपर अढ़ाई-अढ़ाई रुपये में कमरे मिलते हैं ।”

और अपनी पार्टी को लिये हुए भल्ला साहाब धड़धड़ाते हुए ऊपर पहुँचे और कुछ देर बाद वापस आकर नाक-भौं चढ़ाते हुए बोले, “बड़े गंदे और अँधेरे कमरे हैं, आप इनमें कैसे उतर गये !”

और वे आगे कोई अच्छा, हवादार और खुला होटल देखने के ख़याल से चले गये ।

उनके जाते ही मेरी बीवी ने शिकायत की, “आप बस यहीं बैठ गये, ज़रा हिम्मत कर आगे-पीछे देखते तो क्या हमें भी कोई अच्छा और सस्ता कमरा न मिल जाता ?”

“Tell me, Artist Sahab, where have you booked a room?” Bhalla Sahab said as he climbed the stairs. “Oh, hello! We’re just drinking chai for the time being,” I laughed, “If we have the energy, we’ll look for a room.”

“But it’s getting late.” “If we can’t find anything else, we’ll stay right here,” I said wearily, “Our luggage has been brought here. You can get rooms for only two and a half rupees each upstairs.” And, taking his party with him, Bhalla Sahab stomped upstairs; a little while later he came back, turning up his nose in contempt: “Those are very dirty and dark rooms; how did you land on one of them!” And he left, thinking he could find a decent, airy and spacious hotel further ahead. As soon as he left, my wife began complaining, “You just sat down here; if you had taken a little initiative and looked around, wouldn’t we have found a decent, cheap room too?”

“बीबी जी, झक मारकर ये लोग यहीं आयेंगे ।” होटल वाले ने उसकी बात सुनकर कहा, “रेस्ट-हाउस भरा पड़ा है । ख़ेमे कुछ आगे लगे हैं । पर एक तो उनमें ठण्ड है, दूसरे किराया फ़ी ख़ेमा तीन रुपये है । हमसे सस्ता और आरामदेह होटल बटोत में दूसरा नहीं मिल सकता । आपको कोई कष्ट हो तो हम हर तरह की सेवा के लिये तैयार हैं, ये लोग डेढ़ रुपये में कमरा चाहते थे । दस मिनट ऊपर बहसते रहे । सारे बटोत में घूम आयें, हमारे होटल से सस्ती जगह इन्हें कहीं नहीं मिल सकती ।”

“Madam, those people will come right back.” Hearing her (the Artist’s wife), a hotel employee said, “The rest house is full. The tents are set up a bit further ahead. But, for one, they’re very cold and, second, the fee is three rupees. You won’t find a cheaper or more comfortable hotel than this in Batot. If you experience any discomfort, we’re ready to serve you in any way; those people wanted a room for one and a half rupees. They kept arguing for ten minutes upstairs. Even if they wander all over Batot, they won’t find a cheaper place than this anywhere.”

और होटल वाले की बात ठीक थी । कोई आध-एक घंटे के बाद भल्ला साहब अपनी पार्टी के साथ वापस आ गये । हम पर एहसान जमाते हुए उन्होंने कहा, “लीजिए आर्टिस्ट साहब, हम भी यहाँ आ गये ।” और फिर उन्होंने चोपड़ा आदि की ओर इशारा करते हुए कहा, “ये लोग ज़्यादा खुला और हवादार कमरा चाहते थे, पर मैंने इनसे कहा कि सफ़र में हमेशा इकट्ठे रहना चाहिए । इसलिये सोचा कि यहाँ आप ठहरे हैं, वहीं हम ठहरें ।”

And the hotel employee was right. After about thirty minutes to an hour, Bhalla Sahab came back with his party. As if doing us a great favor, he said, “There, Artist Sahab, we’re staying here too.” And then he said, gesturing toward Chopra Sahab and the rest, “They wanted a more spacious and airy room, but I said to them that travelers should always stay together on a journey. That’s why I thought: wherever you’re staying, we’ll stay there too.”

और वे होटल वाले को एक ओर ले गये और पन्द्रह-बीस मिनट तक उसके साथ सयगोशियों में झगड़ते रहे । एक बार हमने उनकी आवाज़ सुनी—“तो हम सामने चले जायेंगे, यहाँ से कहीं बड़े कमरे हैं ।”

लेकिन होटल वाला टस-से-मस न हुआ, आख़िर उन्होंने एक कमरा ले लिया ।

“और चारपाई दरकार हो तो चार आना फ़ी चारपाई मिल सकती है ।” होटल वाले ने वापस आये हुए कहा ।

“हम तो वे भी निकाल देंगे,” ऊपर कमरे की और जाते हुए उन्होंने कहा, “खटमलों में हमें कभी नींद नहीं आती ।” और फिर मेरी ओर देखकर बोले, “आप भी आर्टिस्ट साहब, फ़र्श पर ही बिस्तर लगाइएगा ।”

And he took the hotel employee to one side and kept fighting with him in whispers for fifteen to twenty minutes. Once, we heard his voice—“Then, we’ll go across the street, there are much better rooms there.” But the hotel employee didn’t budge an inch; finally, Bhalla Sahab took a room.

“If you need another cot, you can get one for four aanas.” The hotel employee said as he was coming back. “We’ll take those out too,” Bhalla Sahab said while going upstairs, “We’ve never been able to sleep on bed bugs anyway.” And then, looking in my direction, he spoke, “You too, Artist Sahab, make up your bed on the floor.”

चोपड़ा साहब दिल्ली के एक प्रसिद्ध अँग्रेज़ी दैनिक के सम्पादन-विभाग में काम करते थे, अच्छा वेतन पाते थे और मेरा ख़याल था कि भल्ला और चोपड़ा साहब ने अलग अलग कमरे लिये होंगे, लेकिन सुबह पता चला कि भल्ला साहब ने उन्हें मजबूर कर दिया था कि वे उन्हीं के साथ रहें । “अरे भाई, आप चारपाइयों पर सोना चाहते हैं, आप अंदर कमरे में सोइये । हम बरामेदे में बिस्तर लगा लेंगे, हम तो यों भी खुली हवा पसंद करते हैं ।” उन्होंने कहा था और चोपड़ा साहब को ज़बरदस्ती अपने साथ ही रात काटने पर विवश कर दिया था । और इस तरह दोनों ने सवा सवा रुपये में मज़े में रात काट ली थी ।

Chopra Sahab worked in the editing department of one of Delhi’s famous English daily newspapers; he made a good salary. I thought that Bhalla and Chopra must have taken separate rooms, but in the morning I found out that Bhalla Sahab had forced Chopra to let him stay with them. “Oh, brother, your family wants to sleep on the cots; so, you sleep inside the room. We’ll make our beds on the veranda, we like the open air anyway,” he had said. And, thus, helpless, Chopra Sahab was compelled to spend the night with the Bhallas. And, in this way, both of them enjoyed the night for only one and a quarter rupees each.

खाना भी उन्होंने होटल में न खाया था । जब हमने उनसे कहा कि खाना इस होटल में बहुत अच्छा मिलता है तो वे बेपरवाही से बोले थे कि वे अँगीठी-कोयले साथ लाये हैं, इसलिये मज़े से अँगीठी जलायेंगे, पराँठे बनायेंगे, मुर्ग़ तो सस्ते मिलते हैं, मुर्ग़ पकायेंगे और जश्न मनायेंगे ।

He (Bhalla Sahab) didn’t even eat in the hotel. When we told him that you could get very good food in this hotel, he said carelessly that he had brought a brazier and coal with him; therefore, he would fire up the brazier with glee, make parathas, cook chicken (chicken could be gotten cheaply anyway) and have a celebration.

Unfortunately, the entire story is too long to fit into a blog format but, if you’d like to read the small part of the story that is left, I highly recommend Daisy Rockwell’s translation of some of Ashk’s short stories, entitled Hats and Doctors.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

Navjot Mundra:

Hi Rachael… I am an undergrad at Shiv Nadar University in Noida where I’m pursuing a degree in English research. At the moment, I’m enrolled in a translation course. For my assignment, I would really like to translate तूफान से पहले but I have had no luck finding it. Do you, by any chance, know an online resource where I could find it or has it disappeared completely?

Rachael:

@Navjot Mundra Hi Navjot,

I would check out Diana Dimitrova’s work, especially her book called “Western Tradition and Naturalistic Hindi Theatre.” She’s done a lot of work on Ashk and, particularly, his plays, so looking in her bibliography section would probably help a lot. She also has a book entitled “Gender, Religion and Modern Hindi Drama” that includes discussions of Ashk’s dramatic work and might be worth checking out. The play is most likely included in a collection of Ashk’s dramatic works rather than as a stand-alone play (you could check out “मुखड़ा बदल गया” as I believe this is a collection of plays that may contain “तूफ़ान से पहले۔” I hope this helps!