Móðir mín í kví, kví. Posted by hulda on May 27, 2012 in Icelandic culture, Icelandic history

“Icelandic ghosts are so different from the ones in my homecountry”, a classmate of mine told me once while explaining why she wanted to write her þjóðsögur ritgerð, folk tales essay, about them. Even having a completely different background I had to agree. Icelandic ghosts, draugar, are really a type of their own. They can be divided into certain groups that occasionally overlap each other a bit, but usually they tend to be quite easy to tell apart.

“Icelandic ghosts are so different from the ones in my homecountry”, a classmate of mine told me once while explaining why she wanted to write her þjóðsögur ritgerð, folk tales essay, about them. Even having a completely different background I had to agree. Icelandic ghosts, draugar, are really a type of their own. They can be divided into certain groups that occasionally overlap each other a bit, but usually they tend to be quite easy to tell apart.

Afturgöngur are perhaps one of the most common type. They’re the spirits of people who have killed themselves in desperate circumstances and are usually after the people they felt wronged them, no matter how rightful the act would seem to others. Miklabæjar-Solveig is a good example of this. It tells the tale of a woman who fell in love with a priest but alas, he did not return her feelings. In a bout of depression she slit her throat with shears and returned to haunt the priest until at long last he disappeared, and it’s believed that she finally managed to kill him like she intended to.

An afturganga can also simply be worried for its belongings and guard a place where it hid its money while alive. Another type of a ghost who guards treasures are fépúkar/fédraugar, people who loved their worldly belongings (usually gold) so much that they let some of it be buried with them. This gold weighs their soul into a place and they have to stay with it and keep it safe from others. This ghost type seems to be quite old since the sagas mention killing slaves and burying them with treasure so that their spirits would attack whoever tried to steal it – a theme made more famous by pirate stories later on.

Uppvakningar and sendingar are, like the names suggest, woken from death and zombie-like. They are sent to harm someone by whoever managed to rise them from death. Then there are ghosts named after where or when they occur – dagdraugur can be seen during the day, sædraugur is only seen at sea, and so on.

Mórar and skottur are gangári-type ghosts, meaning that they follow someone instead of being tied into a place (place specific ghosts would be called staðárar). Mórar are male ghosts who often wear something brownish or rust red, usually a shirt or a sweater, and skottur are their female counterparts. The female ghosts wear the same blood-like colour somewhere about them but more importantly they also wear the traditional women’s headdress, kvenhöfuðbúnað, which has a curving plate on top – except that a skottur wears hers backwards so that instead of turning forward, the top piece is pointing to the back.

Perhaps the scariest and saddest type of Icelandic ghost is, however, the útburður. They are the ghosts of children that were killed in infancy, usually by their parents. As the name suggests they were often carried outside and were then left to die in the wild. They are a gangári type ghost meaning they can follow their victims but unlike the other ghosts they can actually cast a curse on a whole family for generations to come. The song in the video above comes from one of the most well-known Icelandic ghost stories.

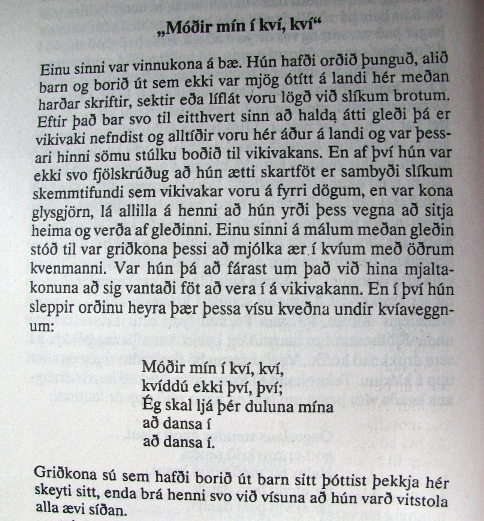

You can practice your Icelandic on the text example above! In short the story goes:

Once there was a worker woman who had become pregnant. She gave birth in secret, wrapped the child in rags* and abandoned it.

Later that year a fest called Vikivaki** arrived. The woman felt she could not attend, having no good clothes for it. Once when she was milking the ewes with another woman she told her about this problem. Suddenly, from below the floor, they both heard something sing:

“My mother in the sheep pen

Don’t you worry

I will lend you my rags

For you to dance in.”

Upon hearing this the woman quickly went insane.

*Some stories mention this, the one in the picture does not. However, the song assumes it nevertheless. For a really creepy version of the song, go here.

**Vikivaki means both a traditional dance danced in a ring, a type of a song/poem often recited in these occasions and also to a whole fest of dancing. As dancing was at best frowned upon and at worst strictly forbidden by the church, these fests were naturally extremely popular.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

About the Author: hulda

Hi, I'm Hulda, originally Finnish but now living in the suburbs of Reykjavík. I'm here to help you in any way I can if you're considering learning Icelandic. Nice to meet you!

Comments:

Jeremy Hull:

Hello Hulda, I’m a folk dancer from Winnipeg, Canada and I’m looking for lyrics to a song used for a viki-vaki dance. Do you know of any good sources for Icelandic folk song lyrics that I should go to?

hulda:

@Jeremy Hull Hi, and welcome!

I’m afraid I don’t know any vikivaki song lyric sources and my searches yielded very little. Some of the most well-known vikivaki songs that kept popping up though were Ormurinn langi and Regin smiður (both Faroese, but the vikivaki tradition exists in both countries), Ólafur Liljurós, Kvæði af stallinum Kristí, Tófukvæði, Tunnan valt and Ásukvæði. I’ve also heard Sprengisandur sung for a ring dance once.

I’m afraid that the best I can suggest is to use the song titles as search option and go by that. I did find and interesting video of people singing and dancing Ormurinn langi as a vikivaki – plus it comes with Faroese lyrics:

http://youtu.be/Bts_v9mqv3g?list=PLDCA0E0C5452AC6F5