It Started With Donald Duck…And Became a Revolution. Posted by Meg on May 26, 2017 in Icelandic culture, Icelandic customs, Icelandic history

My initial intention with the somewhat winding road of a blog entry below started out as a look at translations of the names of storybook and fable characters – like Donald Duck (as below) – but my research and persistent questions took me down a rabbit hole that I couldn’t bring myself to climb out of. So, without futher ado, I give you:

Donald Duck = Andrés Önd, which comes from Anders And (Danish) – it was probably translated directly from the Danish, which explains the lack of alliteration. It was most likely translated from the Danish because of the strong influence of Denmark at the time – Icelanders were subjects of the Danish kingdom in the 1930s, only claiming their independence in 1944 (“home rule” in 1904).

Which reminds me that – lately, we’ve been hearing a lot of talk about Icelanders losing Icelandic to English. Prior to their independence, Icelanders used the same rhetoric to talk about the Danish presence in Iceland. To be danaður – to be Danish-ed – meant to be refined. The Danes were in general the upper class in Icelandic society.

The rather pointed opinion I received when I posed the question of danish-ness in pre-independence Iceland to a very informed friend was that “the refined part of Icelandic culture was basically Danish culture because Icelandic culture was looked up on as rural and primitive and maybe even kind of gross –whereas Denmark was worldly and mainland.” For example, Icelanders would travel to Denmark for their university education simply because there was no university in Iceland until 1911, when the University of Iceland was founded.

As an aside: it was typically people of means that would travel to Denmark – or people with access to people of means that would be able to go for their education. So the university system was by and large exclusionary, though not closed as such. (P.S. – educational institutions were not open to Icelandic women until 1905).

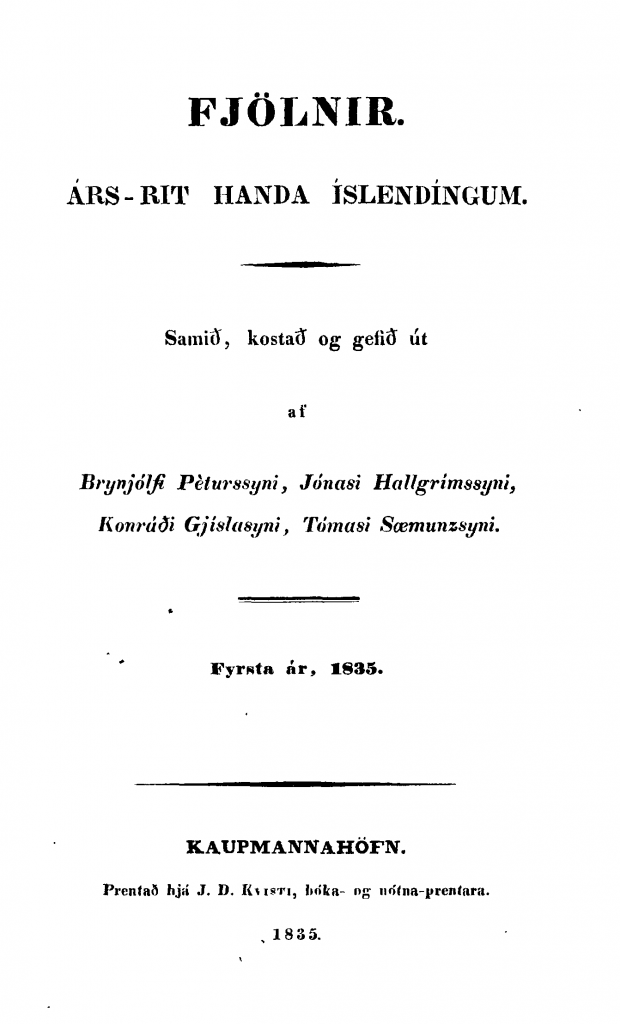

So this rabbit hole led me to four young Icelanders in the 1830s, called the Fjölmennir. The fjölmennir started the journal Fjölnir, which was a politico-literary-historical journal published in Copenhagen by four young Icelandic intellectuals who sought to revive a sort of quintessential Icelandic consciousness and to foster an independence movement. Published from 1835-1847, it’s attributed with having brought romanticism to Iceland (of particular note: Jónas Hallgrímsson’s work featured prominently in the journal).

Fjölnir tried to draw attention – from Copenhagen as the cultural nexus – to the state of affairs in Icelandic society and culture. It proposed three major areas where progress could be made across the board: the reestablishment of the Alþing at Þingvellir, better knowledge of the sagas and Icelandic literature, language, and history, and (as romantics tend to do), a stronger awareness of Icelandic nature. The pamphlet was sharply critical of many things that the older generation of Icelanders had been accustomed to, including their sense of style, mannerisms, language usage, and, naturally, political and economic issues.

And they did it all in Icelandic, at a time when Danish language and culture had a massive influence on Icelandic culture, both domestically and through educational systems abroad.

Literary journals and zines, as a rule, are often used as a means to communicate revolution, to awaken ideas, to reinvent the way we see language and culture- and ourselves within those frameworks. The four founders of the journal – all young men born in Iceland and university educated in Denmark, writing from Denmark — typify revolution, democracy in action, and represent an important step in the Icelandic independence movement, through both the interrogation and preservation of Icelandic-ness.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

Ken Doran:

Ég hlakka að lesa þetta blogg. Takk