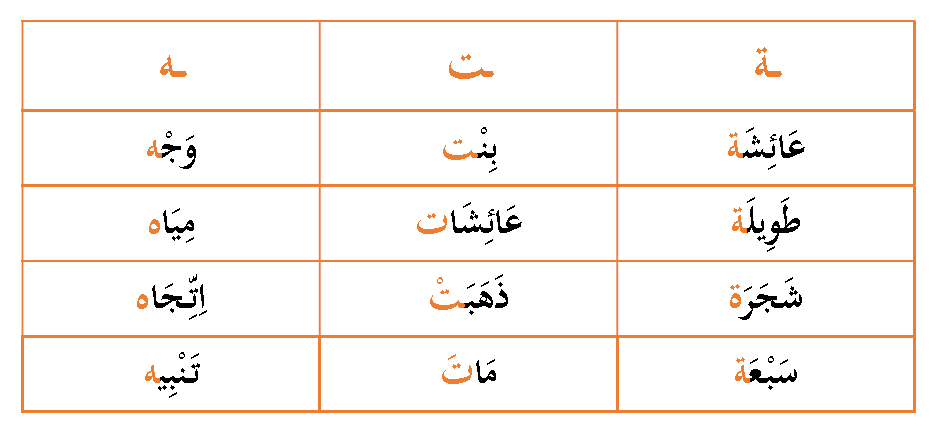

[ت] , [ــة] , or [ــه]: How to Differentiate Between Them? Posted by Ibnulyemen اِبْنُ اليَمَن on Apr 24, 2017 in Arabic Language, Grammar, Pronunciation, Vocabulary

For learners of Arabic, as is the case for native speakers, it is normally difficult to distinguish between [ت], [ــة], and [ــه] when they occur at the end of words. [ت] is called taa maftuHah تَاء مَفْتُوحَة, [ــة] is called taa marbuTah تَاء مَرْبُوطَة , and [ــه] is called haa or haa marbuTah هَاء / هَاء مَرْبُوَطة. While native speakers’ problem is mainly orthographic, Arabic learners’ problems is both orthographic and in pronunciation. How is each of these letters pronounced? What are the similarities and differences between them? Does knowing the right pronunciation help with correct spelling?

1) Pronunciation and Usage:

- التَّاء المَفْتُوحَة:

التَّاء المَفْتُوحَة is always pronounced ت regardless of the type of diacritical mark that goes with it, i.e. fatHah, Kasrah, dhammah, or sukoon (see this blogpost) or their corresponding tanween . Therefore, [ت] is always pronounced as ت in all these cases:

بِنْتْ بِنْتٌ بِنْتًا بِنْتٍ البِنْتَ البِنْتِ البِنْتُ

التَّاء المَفْتُوحَة is used with singular nouns, such as بَيْت ‘house,’ and أُخْت ‘sister’; with feminine plural nouns, such as بَنَاتْ ‘girls’ and مُعَلِّمَات ‘female teachers’; and with verbs as a feminine marker, like ذَهَبَتْ ‘she went’ and كَتَبَتْ ‘she wrote’ and as part of verb, such as مَاتَ ‘he died’ and سَكَتَ ‘he stopped talking.’

- التَّاء المَرْبُوطَة:

التَّاء المَرْبُوطَة is pronounced as هـ when we stop on it (this is called waqf وَقْف in Arabic, which I will elaborate on in another post); in other words, it has a sukoon on it. With all other diacritical marks, it is pronounced in the same way as التَّاء المَفْتُوحَة, but written as ــة, as in these examples:

- As [هـ]:

طَوِيلَةْ ‘tall’ الطَّوِيلَةْ شَجَرَةْ ‘tree’ الشَّجَرَةْ

- As [ت]:

طَوِيلَةً طَوِيلَةٍ طَوِيلةٌ الطَّوِيلَةً الطَوِيلَةِ الطَوِيلَةُ

التَّاء المَرْبُوطَة is used as a feminine marker of proper nouns. That is, almost all proper nouns that end in تَاء مَرْبُوطَة are feminine forms. It is also used to derived feminine forms from masculine. For instance, these adjectives and nouns are in masculine form: نَشِيط ‘active’, ذَكِي ‘intelligent’ and أُسْتَاذ ‘teacher’, عَامِل ‘worker’. Feminine forms are formed by appending ــة to the end, i.e. نَشِيطَة, ذَكِيَّة, أُستَاذَة, and عَامِلَة, respectively.

- الهَاء:

الهاء is always pronounced as هـ whether accompanied by a diacritical marked or not, as in these examples:

وَجْه ‘face’ الوَجْهَ الوَجْهِ الوَجْهُ مِيَاه water’ مِيَاهٌ المِيَاهُ المِيَاهَ المِيَاهِ

الهَاء can be part of the word, as in وَجْه. It is also a possessive pronounce appended to the end of nouns to indicate possession, as in كِتَابُهُ ‘his book’ and أُستَاذُه ‘his teacher.’ If added to the end of verbs, it is normally an object pronoun, i.e. the receiver of the action, as in ضَرَبَهُ ‘he hit him’ and حَبَّتْهُ ‘she loved him.’ It is also add to the end of preposition (called object of a preposition), as in بِهِ ‘with it’ and إِلَيهِ ‘to him.’

2) Similarities and Differences:

- [ت] and [ــة]: they are pronounced in the same way when التَّاء المَربُوطَة is accompanied by tanween or any of the three short vowels. The only difference between the two is that التَّاء المَربُوطَة is pronounced as هـ when we stop on it. Another obvious difference is the way they are written [ت] vs. [ــة]. This is one the difficulties native speakers face. Since they hear ــة as ـت, they write/misspell it as [ت].

- [ــة] and [ــه]: التَّاء المَربُوطَة is basically pronounced as هـ when we stop on it. In this sense, they are the same. This, as a result, constitutes a major difficult for native speakers and learners of Arabic; namely in writing. They write التَّاء المَربُوطَة as هـ all the time given that adding sukoon to word endings has become a commonplace in Modern Standard Arabic. Therefore, words such as جَمِيلَة ‘pretty’, طَالِبَة ‘female student’, مُدِيرَة ‘female manager’ are incorrectly written as جَمِيلَه , طَالِبَه, and مُدِيرَه, respectively.

3) A rule to keep in mind:

- To distinguish between [ت] and [ــة], use taskeen تَسْكِين (adding of sukoon) as a test. If you add sukoon to the [ــة], it is pronounced as هـ rather than ت. If the pronunciation remains ت despite the taskeen, then it is [ت] not [ــة].

- To distinguish between [ــة] and [ــه], use taHreek تَحْرِيك (adding of diacritical marks or tanween). If you add a diacritical mark (other than the sukoon) or tanween to [ــة], it pronounced as ت; conversely, if you use taskeen, it is pronounced as ــه. This way we know whether it is a ــة or a هـ. As cited above, [ــه] is always هـ regardless of تَسْكِين or تَحْرِيك.

Now, let’s put what just leaned into practice. Paying attention to the presence or absence of final diacritical marks, say these words out loud.

دَجَاجَة الغُرفَةُ سُكُوت قَلمَهُ سَاعَات جَامِعَةٍ المَدْرَسةِ حَيَاة حَيَاةٍ الحَيَاةُ حَبِيْبَة سَارَة

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

Scheich Josef:

مرحبا يا ابن اليمن

Your detailed comparison of التَّاء المَفْتُوحَة, التَّاء المَرْبُوطَة, and الهَاء المَرْبُوَطة is surely very useful for beginners.

According to the Langenscheidt dictionary the “ــة” of words with an alif before it is pronounced as “ت” even if we stop on it. See for example the common word صَلاةْ [sˤɑ’laːt] for “prayer”.

Your “rule to keep in mind” is certainly correct, but how can a learner practically apply it, if there is nobody present to pronounce the modified version for him/her? A response of this kind I often get from language students to such rules …

مع السلامة

يوسف

ibn al-Yemen:

أهلاً بالشيخ يوسف، عساك بخير؟

Thank you for stopping by! I appreciate inquisitive comments.

As for your first question, you may want to consult other references. ــة is always pronounced as ــه when we stop on it regardless of the letter the precedes. For instance, in the word حياة, the ــة is pronounced as ــه even though it is preceded by alif, as per your generalized rule. The only time we pronounce ــة as ت even if we stop on it is in Idhafah إضافة structure. Using the word your cited as an example “صلاة”, we say Salat al-fajr “morning prayer” and never Salah al-fajr, even if we stop on Salah.

As for your second comment, motivated language learners will always find way to put into practice what they learn. Technology has made easier for us. Using Transparent Language online software, learners are guided through to perfect skills like this.

Your comments are conducive to more learning, I always look forward to it.

Scheich Josef:

مرحبا يا ابن اليمن

In general the ــة is pronounced as ــه when we stop on it.

In the book “A Reference Grammar of Modern Standard Arabic” published by Cambridge University Press in 2005 its author Karin C. Ryding, a Sultan Qaboos bin Said Professor Emerita of Arabic Linguistics at Georgetown University, lists in Chapter 2 Phonology and script, Section 3.4.3.2, two exceptions from this general rule:

If the word ending in ــة is the first term of an إضافة construction, then ــة is pronounced as ت, even in pause form. This exception is usually also discussed in textbooks for beginners.

The other exception – with which you disagree in your reply above – is as follows: If the ــة is preceded by the long vowel “a”, then the ــة may be pronounced in pause form either as ت or as ــه.

Thus the pronunciation given in the Langenscheidt dictionary for صلاة [sˤɑ’laːt] and similar words is correct.

In the freely accessible online version of this dictionary you can find for حياة the pronunciation [ħa’ja:t] together with an audio file and also the alternative pronunciation [ħa’ja:h].

This last exception is discussed controversially in the thread “pronounciation: alif + ta marbuuTa” of the forum on WordReference.com, .

مع السلامة

يوسف

ibn al-Yemen:

@Scheich Josef أهلاً يا شيخ يوسف

thank you for the reply and the additional comments. As always, I enjoy your comments.

I suppose it is always best to obtain info from the horse’s mouth. In all Arabic grammar books that I studied in school; the university; and in all traditional Arabic grammar books that I read, I never came across the case that you are arguing for, i.e. that ــة is pronounced as ت even if we stop on it.

As well, intuitively, i.e. in the course of my acquisition of Arabic, I never heard people pronouncing it as ت, even in formal settings. Take the case of حَيَّ على الصلاة ‘come to the prayer’, the ـــة is always pronounced as ـــه owing to stopping on it.

مع السلامة