Kashgar (喀什) Posted by Stephen on Nov 29, 2011 in Culture, Uncategorized

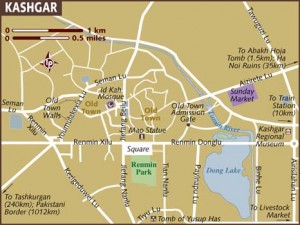

Located roughly 250 km from the borders of Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Pakistan, Kashgar or 喀什 (Kāshí) is a border city of approximately million people located in western Xinjiang Province. The surrounding countryside is almost all desert, with average temperatures sea-sawing between extremely frigid colds and scorching heat (sometimes both happening within 24 hours). It is the cultural center of the Uighur population, an ethnic minority of muslims from the Caucus mountain range.

Located roughly 250 km from the borders of Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Pakistan, Kashgar or 喀什 (Kāshí) is a border city of approximately million people located in western Xinjiang Province. The surrounding countryside is almost all desert, with average temperatures sea-sawing between extremely frigid colds and scorching heat (sometimes both happening within 24 hours). It is the cultural center of the Uighur population, an ethnic minority of muslims from the Caucus mountain range.

Within the city limits, the natural oasis and spring water provides irrigation, agriculture and grazing land for livestock turning this patch of desert land into a pit stop paradise for wayward travelers. Due to its geographic location between China and Central Asia, it became a major stop along the Silk Road for those looking to stock up on supplies.

During the Han Dynasty, Kashgar played an important role as a frontier city for trade and cultural exchange. By establishing what is now generally referred to as the Northern Silk Route, the Chinese had cemented their presence in central Asia while opening up lines to the Middle East and beyond. As the Han Chinese expanded westward they required tributes from neighboring lands and regions. In exchange, the Chinese would share technology and trade routes as incentives for continued business.

By the 1st century AD, merchants from across Asia were calling Kashgar a temporary home as they traversed the vast desert. With those merchants came their respective cultures and creeds, including many eastern religions that have left an indelible mark on the Silk Road. Up through the Tang Dynasty, the influx of Buddhist pilgrims influenced many followers to convert within the city. Daoism and Confucianism also made their way west from central China. Centuries later Islam would come to dominate the religion in this area. However, in this transitional time peroid (7th and 8th centuries), Kashgar was without a true identity as a series of conflicts among the Mongols, Chinese and Turkic tribes fragmented the region, left the region a scattered mix of various tribes, cultures and ethnicities.

Amidst subjugation and infighting, Kashgar faltered, and didn’t emerge again as powerhouse of trade until Arab conquest of the late 8th and 9th centuries. While Islam was charging across the Middle East and up into Central Asia, the Silk Road acted as an ancient “super highway” spreading Muslim culture throughout the region. By the late 10th century Kashgar and its followers had almost all converted to Islam under prince Sultan Satuq Bughra Khan, establishing the Uighur Kingdom.

The Uighur Kingdom, while short lived in rule, established many of the rules and customs of Uighur culture that are still practiced today. While power, influence and control of land shifted back and forth among the Turks, Mongolians, and Chinese, people within Xinjiang and Kashgar remained true to their Silk Road roots.

The Uighur Kingdom, while short lived in rule, established many of the rules and customs of Uighur culture that are still practiced today. While power, influence and control of land shifted back and forth among the Turks, Mongolians, and Chinese, people within Xinjiang and Kashgar remained true to their Silk Road roots.

These people, known as Uighurs–维吾尔族人 (wéi wú ěr zú rén) or 维语 (wéi wú) for short [Uighur: قەشقەر] have continued to carry out the same traditions and practices that existed nearly a millenium ago. Because of their adherence to Turkic rituals and very strong traditions of practice and observance within the muslim faith, the Uighurs are quite unique to the rest of China’s ethnic makeup. While their roots are nomadic, Uighur society is strengthened around Muslim beliefs and as a result have a very strong sense of community. Their culture has existed for thousands of years without having to change much and the people take pride in this fact.

In modern day Kashgar, the city is divided entirely by two distinct ethnic lines, between the developing, metropolitan Han Chinese population and the isolated, almost pre-industrial population of the Uighurs. Kashgar is famous for its Uighur livestock market (see photos below) where traders and farmers conduct an ancient system of bartering–using only their hands. Check it out (at 0:30):

Once you’ve wandering through the endless acres of cattle and livestock, you can head on over to the Kasghar Bizarre which I can only describe as a gargantuan open air complex of lean-to stalls snaking endlessly through a labyrinth of Muslim architecture.

Once you’ve wandering through the endless acres of cattle and livestock, you can head on over to the Kasghar Bizarre which I can only describe as a gargantuan open air complex of lean-to stalls snaking endlessly through a labyrinth of Muslim architecture.

The place is massive. Anything you need–literally anything–you can find at this bizarre. While I couldn’t pick up on the hand bartering system in my short stay, I soon found that everything at the bizarre had a “just fell off a truck” price to it. Just watch your wallet and be prepared to barter like you’ve never bartered before, this time in a combination of English and Chinese and broken Uighur phrases.

Outside of the bizarre and markets sits the “Old City” of Kashgar where the majority of Uighur residents live. This area has a timelessness to it that makes you feel as if you were transported some centuries back. Mosques are everywhere and so is evidence of a strongly muslim culture. Because of centuries of conflict and the desire for autonomy, “Old City” Kashgar has stagnated economically–by simply not being involved in the modern economy.

Poverty is apparent on every street and stands as a strong reminder that without a strong muslim social safety net, many people here would starve.While on aggregate China’s GDP booms and incomes rise, this part of China is stuck looking in from the outside, waiting for a chance when growth and development will come Kashgar’s way. Questions still remain: how long can the Uighurs sit idly by as tension and restlessness continues to rise? Is it independence or inclusion that people are after?

Poverty is apparent on every street and stands as a strong reminder that without a strong muslim social safety net, many people here would starve.While on aggregate China’s GDP booms and incomes rise, this part of China is stuck looking in from the outside, waiting for a chance when growth and development will come Kashgar’s way. Questions still remain: how long can the Uighurs sit idly by as tension and restlessness continues to rise? Is it independence or inclusion that people are after?

No doubt you’ve heard of the riots and violence that has dominated headlines in Xinjiang for the last decade. Social unrest is a constant problem in these areas where unemployment, poverty, substance abuse and radicalization of Islam are becoming incredibly taxing on development. The disconnect between Han and Uighur culture has forced a societal rift between neighbors of the same city. Ironic that a millennium ago Kashgar was the forefront of cultural exchange and diversity. Now it’s a tale of two cities–one past and one present.

Follow Steve on twitter: @seeitbelieveit

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

About the Author: Stephen

Writer and blogger for all things China related. Follow me on twitter: @seeitbelieveit -- My Background: Fluent Mandarin speaker with 3+ years working, living, studying and teaching throughout the mainland. Student of Kung Fu and avid photographer and documentarian.

Leave a comment: