History of the PRC – Part Fourteen Posted by sasha on Mar 2, 2011 in Culture, Uncategorized

With the New Year festivities behind us, it’s time to dive back into our history lesson on the tumultuous period between China’s last Emperor and the founding of the modern day People’s Republic of China. When we last left off in Part Thirteen, Chiang Kai-shek and his army had just suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of the Japanese in the Battle of Shanghai, part of the Second Sino-Japanese War.

While this was a devastating loss for China, things would only get worse. After taking Shanghai, the Japanese forces decided to move on to the city of Nanjing (南京 – Nán jīng). Literally translated as “Southern Capital,” this city was actually the capital of China at this time. Realizing that the Japanese invasion of Nanjing was inevitable, Chiang – along with most of his army – moved inland. This was a strategy recommended to him by Germany – to use China’s vast territory as a defense mechanism. For the time being, the capital was moved to Chongqing (重庆 – Chóng qìng).

With Chiang, the army, and the government gone, Nanjing’s defense was left to an International Committee and citizens . Although there were plenty of Chinese ready to defend the city, you can imagine their loss of confidence and morale when they saw soldiers fleeing from Shanghai and the destruction they had experienced there. What happened next is one of the darkest events in China’s long and often troubled history.

As the Japanese made their way from Shanghai to Nanjing, many citizens fled the city in anticipation of the battle that was sure to come their way. Not only were they running from the Japanese, however, but they were also trying to escape the self-inflicted damage that had been called for by the KMT when it was announced that everything in Nanjing would be turned to ash before it would be turned over to the enemy. Many buildings, houses, and even entire villages went up in flames.

Arriving outside of the city on December 9, 1937, the Japenese urged that Nanjing be surrendered within 24 hours. Despite a proposal, agreed on by the invading Japanese, for a three-day cease fire to allow people and soldiers to flee the city, Chiang refused and ordered that Nanjing be defended “until the last man.” With Chiang’s refusal, the Japanese moved to take Nanjing by force, which resulted in complete and utter chaos. Many Chinese soldiers, terrified of the fate that lay before them, even went so far as to strip civilians of their clothes in order to blend in. Some were even shot down by their own superiors as they tried to flee. Within one week, the Japanese had taken control of the city.

The next six weeks of horror have come to be known as the “Nanjing Massacre” (南京大屠杀 – Nán jīng dà tú shā), or even the “Rape of Nanjing.” One website, www.nanking-massacre.com, sums up the events that took place as follows:

“During the Nanking Massacre, the Japanese committed a litany of atrocities against innocent civilians, including mass execution, raping, looting, and burning. It is impossible to keep a detailed account of all of these crimes. However, from the scale and the nature of these crimes as documented by survivors and the diaries of the Japanese militarists, the chilling evidence of this historical tragedy is indisputable.”

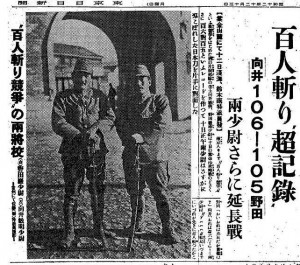

Various written and photographic accounts of the Massacre exist, and they are disturbing to say the very least. It is said that there was a competition – deatails of which were published in newspapers – between two Japanese soldiers to see who could kill 100 Chinese first. Pregnant women were raped and then stabbed in the stomach with a bayonet. There were beheadings and cases of people being buried alive. Some estimate the death toll from this horrific time at 300,000.

Now, over 70 years later, the Nanjing Massacre is still very much a touchy subject in China. Although Japanese Prime Minister Tomiichi Murayama finally issued a clear and formal apology for Japan’s actions in 1995, some still denounce that the massacre ever happened. Many Chinese still harbor animosity and distrust toward Japan as a result. In 1985, the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall (侵华日军南京大屠杀遇难同胞纪念馆 – Qīn huá rì jūn nán jīng dà tú shā yù nàn tóng bāo jì niàn guǎn) was constructed in rememberance of those killed. This museum is located near an area where thousands of bodies were buried, known as the “pit of ten thousand corpses” (万人坑 – wàn rén kēng). Having visited this museum personally in 2009, I can only say that it is a sombering experience.

Video from Al Jazeera English on the 70th Anniversary of the Nanjing Massacre.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

About the Author: sasha

Sasha is an English teacher, writer, photographer, and videographer from the great state of Michigan. Upon graduating from Michigan State University, he moved to China and spent 5+ years living, working, studying, and traveling there. He also studied Indonesian Language & Culture in Bali for a year. He and his wife run the travel blog Grateful Gypsies, and they're currently trying the digital nomad lifestyle across Latin America.

Leave a comment: