Stay in Tone! Posted by sasha on Feb 14, 2011 in Vocabulary

When it comes to learning Chinese, understanding how to 读 and 写 the thousands upon thousands of 汉字 is obviously the most difficult part of the learning process. However, if you are simply interested in learning how to 说中文, you will probably encounter the most difficulty whilst attempting to learn the four 声调 (shēng diào – tones) that are used in Mandarin.

As a native English speaker, I was completely befuddled by the concept of a tonal language when I first arrived in China. Needless to say, the concept of constantly raising and lowering my voice in order to be properly understood took some getting used to. When I finally got fed up with relying on friends, phrasebooks, and charades to be understood, and decided to get a Chinese 辅导 (fǔ dǎo – tutor, lit. coach), we spent the first few weeks entirely on learning the 拼音 system and drilling the tones. During those few weeks, there were plenty of times when I was ready to give up hope all together, as I was convinced that I would never be able to properly utilize the tones. Thankfully, with loads of encouragement from my tutor, I chose to persevere. I listened to her 发音 (fā yīn – pronunciation) carefully, as well as people outside, my audio books, and Chinese 电视节目 (diàn shì jié mù – television programs), always trying my best to mimic the sounds. With time, utilizing the tones started to come more naturally, and I even started getting compliments on my pronunciation, which, to be honest, still isn’t very good at all. But that’s the thing with learning Chinese – if you make a concerted effort, and come close, people will for the most part understand you, and will often compliment you. Although you can get away with mixing up your tones (believe me, I do it a lot), it’s still vital for new learners to focus their attention on learning to recognize and use the four tones. Here is a little crash course 老外 style in the four tones of Chinese:

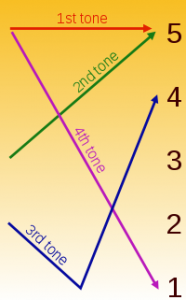

第一声 (dì yī shēng – the first tone) – For tone #1, your voice starts high and stays that way, kind of like your hippie roommate in college. Do you remember singing do-ray-me-fa-so-la-ti-do in music class? Well, when pronouncing a syllable with the first tone, your voice should sound like it does when you hit that last “do”.

第二声 (dì èr shēng – the second tone) – On to tone #2. The best way I can relate the second tone to something in English is the way you raise your voice when asking a question. You voice starts somewhere in the middle, and rises to the top. For a great cinematic example, look no further than Ron Burgundy’s teleprompter mishap in “Anchorman”:

If you just pretend like you are asking a question every time you use the second tone, you’ll do just fine.

第三声 (dì sān shēng – the third tone) – This one is by far the most difficult, if you ask me. Your voice needs to start in the middle, drop to the bottom, and then raise up near the top. When I started out, the third tone was the bane of my existence, and I was constantly screwing it up. It’s difficult to relate to English, but it’s somewhat akin to the way you would give a very surprised “Whhhhaattt?!” in response to a shocking statement from a friend. For example, a few years ago, when I told friends I was moving to China, they would often reply as such – “Whhhaaattt?! You’re moving to CHINA?!”

第四声 (dì sì shēng – the fourth tone) – Finally, there is the falling sound of the fourth tone. This one is pretty easy. Your voice starts high and drops all the way down. Basically, you sound like you are angry when using the fourth tone. Pretend like you’re dog just chewed up your favorite pair of Nikes (“BAD dog!”) or flash back to your younger years and your parents scolding you (“You’re GROUNDED!”). Harness that anger, and you’ve got the fourth tone down.

轻声 (qīng shēng – the neutral tone, lit. gentle voice) – Oh, wait, you thought we were finished? Ha! Think again. In Chinese, there is also a neutral tone. When reading pinyin, you can spot this one by the lack of tone identifier. Some common places you will see the neutral tone are at the end of a sentence, when asking a question, or when a syllable is repeated (the second one will have the neutral tone). Just as it implies, your voice should be gentle, with no rising or falling.

你清楚吗? (nǐ qīngchu ma – do you understand?/is it clear?) If not, don’t worry about it. As my tutor told me when I was ready to give up, “多听多说, 不怕出错“ (duō tīng duō shuō, bù pà chū cuò – listen more and speak more, don’t be afraid of making mistakes). As long as you practice and actively listen when you hear other people speaking Chinese, you’ll improve. Of course, you don’t want to call your 妈妈 (mā ma – mother) a 马 (mǎ – horse), but that might happen when you first start out learning and speaking Chinese.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

About the Author: sasha

Sasha is an English teacher, writer, photographer, and videographer from the great state of Michigan. Upon graduating from Michigan State University, he moved to China and spent 5+ years living, working, studying, and traveling there. He also studied Indonesian Language & Culture in Bali for a year. He and his wife run the travel blog Grateful Gypsies, and they're currently trying the digital nomad lifestyle across Latin America.

Comments:

colvks:

The problem of fayin is more enhanced if the learner is English speaking from USA and UK.