Wǔ Shù (武术) Posted by Stephen on Sep 26, 2011 in Culture

Kung fu is a modern day phenomenon that is more of a culture than the actual practice of Chinese martial arts. Wushu or 武术 (wǔ shù) on the other hand, is a broader term that refers to the many schools (門, mén), families (家, jiā) and sects (派, pài) of Chinese fighting. Much like 功夫, 武术 translates as “martial art” or “fighting skill” and has led to the mastery of a myriad of different styles involving every limb, weapon and tantric practice within Chinese borders.

Kung fu is a modern day phenomenon that is more of a culture than the actual practice of Chinese martial arts. Wushu or 武术 (wǔ shù) on the other hand, is a broader term that refers to the many schools (門, mén), families (家, jiā) and sects (派, pài) of Chinese fighting. Much like 功夫, 武术 translates as “martial art” or “fighting skill” and has led to the mastery of a myriad of different styles involving every limb, weapon and tantric practice within Chinese borders.

But wu shu’s roots didn’t start within China, so to truly trace the history of this famous form of martial arts, we have to take another quick trip west along the Silk Road back nearly 4,000 years ago. During this time, hunters and nomadic peoples in this frontier area needed a way to protect themselves and drew upon the variety of fighting cultures (including boxing, wrestling and sword play) from distant lands. Over the years, cultural interaction led to the development of specific fighting styles across central Asia. By the time these travelers crept into China, some semblance of a “martial arts” had taken hold–only to be drastically altered and Sino-cized.

Soon Shǒubó (手搏) emerged as a the precursor to 武术, and by the 7th century BCE, Sanda (kickboxing) had evolved into a uniquely Chinese practice. Sun Tzu (author of The Art of War) was quick to include shoubo in his military strategies and made sure all his ground troops could fight unarmed. Seen as a way to empower guards and strengthen the military, 手搏 wasn’t embraced by the citizens (老百姓) until Confucius (孔子 kǒng zi) decreed that the Chinese people should practice both physical and literary arts to improve their overall quality of living. Thus, the athlete-scholar first emerged within the Chinese ranks emphasizing Daoist concepts of finding balance and harmony between mind and body. After all, what Confucius says, goes (孔子说…).

Soon Shǒubó (手搏) emerged as a the precursor to 武术, and by the 7th century BCE, Sanda (kickboxing) had evolved into a uniquely Chinese practice. Sun Tzu (author of The Art of War) was quick to include shoubo in his military strategies and made sure all his ground troops could fight unarmed. Seen as a way to empower guards and strengthen the military, 手搏 wasn’t embraced by the citizens (老百姓) until Confucius (孔子 kǒng zi) decreed that the Chinese people should practice both physical and literary arts to improve their overall quality of living. Thus, the athlete-scholar first emerged within the Chinese ranks emphasizing Daoist concepts of finding balance and harmony between mind and body. After all, what Confucius says, goes (孔子说…).

As wu shu had gone mainstream, sects of fighting styles emerged throughout the mainland. By the 4th century, Daoist and Buddhist influences mixed with Kung fu culture offering up new concepts of qi manipulation (qì or ”气“ is the “life energy” of all living things).

From there two forms of qi manipulation, internal (内家拳, nèijiāquán) and external (外家拳, wàijiāquán) were developed with the former focused on storing up this energy, and the later, of releasing it through physical activity.

Soon concepts of meditation, including breathing exercises known as 气功 (qì gōng) became commonplace as the search for spirituality forced many monks to look inward. Daoist philosophies became synonymous with wu shu practices, with Buddhism quickly following suit. Citizens young and old, from all walks of life, gravitated towards the multitude of mind-body activities that had sprung up in just a few centuries. Culturally, Kung fu was enmeshed in everyday life.

Yet as kung fu became more popular, a divergence between common and esoteric practices became more pronounced. While the “weekend warriors” of kung fu practiced it as a compliment to academic learning, religious sects and the imperial guard directed the study of wushu towards institutionalization.

It was around this time that various schools of kung fu or wushu began popping up throughout China, most notably: Shaolin (少林), Kunlun (昆仑) and Wudang (武当). These schools were prized by the Imperial court as the top fighters became guards and protectors of the Imperial family, standing as a front line to many invading forces or clans and serving as body guards.

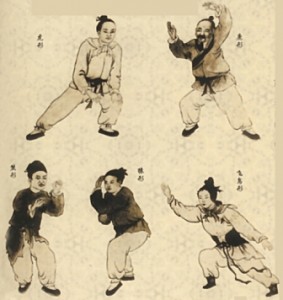

Emerging from this mix of institutionalization, militarization and religious indoctrination are many of the styles of kung fu that we see today, including the “5 Animals” fighting styles (tiger, deer, monkey, bear, and bird), taichi, and Bagua. For centuries, monks, soldiers and swordsmen honed their fighting craft, relying on passed down wisdom in a relentless pursuit of perfection to drive them towards the most efficient and lethal strikes in all of martial arts.

Just watch as this Shaolin monk harnesses his “qi” and focus to drive a needle through a sheet of glass (without shattering it), and popping a balloon on the other side:

Yet in balancing these violent fighting styles with meditative, Buddhist practices, an opposite but equally significant culture of peace and tranquility emerged right along side the high flying kicks. The duality of wu shu had thus solidified itself. China had developed a practice equal parts mind and body.

Follow Steve on twitter: @seeitbelieveit

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

About the Author: Stephen

Writer and blogger for all things China related. Follow me on twitter: @seeitbelieveit -- My Background: Fluent Mandarin speaker with 3+ years working, living, studying and teaching throughout the mainland. Student of Kung Fu and avid photographer and documentarian.

Comments:

Steven C. Poling Jr.:

Kungfu is not a sect of wushu.