Yes? No? Maybe so. Posted by Stephen on Sep 15, 2011 in Culture

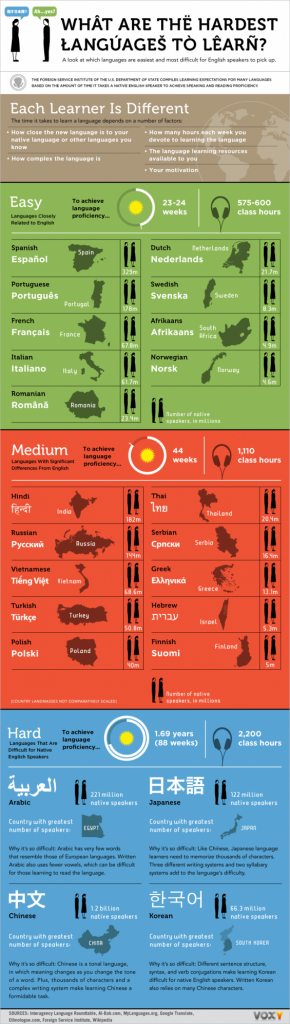

Most people learning Chinese have exclaimed that “it’s like learning two, if not three new languages all at once”. While it may not be as difficult as learning Chinese, Japanese and Korean at the same time, there is some truth in this. Let’s take the process of learning beginning Chinese.

Most people learning Chinese have exclaimed that “it’s like learning two, if not three new languages all at once”. While it may not be as difficult as learning Chinese, Japanese and Korean at the same time, there is some truth in this. Let’s take the process of learning beginning Chinese.

First, before even looking upon a character, you are taught radicals (the basic pictographic components of characters or 汉字). However, what good is recognizing a radical for “moon” or “sun” if you don’t know how to say it? So next we learn Pin Yin or the standardized phonetic romanization form of Chinese language (Wade Giles is no longer considered standard, and frankly it is counter-intuitive).

But within this step is also a challenge. Chinese is a tonal language based on specific words, not syntax or grammar (like English). Now you have to learn the pronunciation of words, coupled with the specific tone (there are four), plus you have to start making sounds and noises that your western tongue is unfamiliar with. After you’re able to recognize and say words, then comes grammar patterns and sentence structure. Now you can see why it is said to take around four to five times the practice and training to learn as any romance language:

But as I’ve found living, working and teaching in China, learning the above mentioned steps isn’t a guarantee that you’ll achieve conversational fluency (流利 liú lì). Remaining in your pursuit for fluency is the influence of culture (文化 wén huà) upon Chinese language. While you may be able to speak and even sound like a Chinese person, odds are your frame of mind, thinking and attitude (态度 tài du) are still not Sino-centric. Put another way: you may have all the ingredients to make dumplings, but if you don’t know what steps to follow and how to mix everything together, no 饺子 for you.

But as I’ve found living, working and teaching in China, learning the above mentioned steps isn’t a guarantee that you’ll achieve conversational fluency (流利 liú lì). Remaining in your pursuit for fluency is the influence of culture (文化 wén huà) upon Chinese language. While you may be able to speak and even sound like a Chinese person, odds are your frame of mind, thinking and attitude (态度 tài du) are still not Sino-centric. Put another way: you may have all the ingredients to make dumplings, but if you don’t know what steps to follow and how to mix everything together, no 饺子 for you.

Trust me, it sounds weird, but you have to think like a native Chinese speaker. Sometimes, this requires a “dumbing down” of the sentence you want to say (remember Chinese uses lots of shorts phrases to convey meaning). Other times, the sheer complication of English grammar (including prepositions and peculiarities that even I don’t understand) causes you to formulate a phrase or sentence in your mind that is awkward and convoluted in Chinese. My suggestion is to keep it simple (简单点 jiǎn dān diǎn), and be mindful of cultural discrepancies that don’t translate.

A key example of the disconnect culturally between Western and Chinese thinking is the use of “yes” and “no”. In western culture, yes and no are the quintessential words that everyone learns first. After all, in our language and culture, “yes” and “no” are immensely important. They either confirm or deny an question, suspicion or request with absolute certainty.

A key example of the disconnect culturally between Western and Chinese thinking is the use of “yes” and “no”. In western culture, yes and no are the quintessential words that everyone learns first. After all, in our language and culture, “yes” and “no” are immensely important. They either confirm or deny an question, suspicion or request with absolute certainty.

Considering that almost every western society is based upon the legacies of Greek, Roman or Renaissance thinking (where legality and contractual obligations emerged), romance language speakers need this concrete system of “yes” and “no” in order to remove any question or doubt of agreement. Further principles of the rights of individuals, and rights of law require a system removing any confusion of what “yes” or “no” means from one individual to another.

Yet, China lacks a history of “rule by the word of law”, a legal system, or individual rights. Under Confucian principle, people were taught to see themselves as parts of a community–not individuals–which required less of a legal framework to carry out laws, punishments or agreements. In such a society, intended meaning is in the eye of the beholder, so naturally interpretation varied by person.

Yet, China lacks a history of “rule by the word of law”, a legal system, or individual rights. Under Confucian principle, people were taught to see themselves as parts of a community–not individuals–which required less of a legal framework to carry out laws, punishments or agreements. In such a society, intended meaning is in the eye of the beholder, so naturally interpretation varied by person.

To this day, business practices, agreements and contracts in China are more reliant upon building up of mutual trust/networking (关系) and verbal agreements based on personal understanding of a vague contract. Here’s a video example of how to use Chinese to convey a “yes” or “no” meaning:

As a result, the Chinese language never really established a concrete way to say “yes” or “no”. In Chinese, conveying affirmative or negative actions is carried out by the verb of the sentence. That is to say, in Chinese, answering in the affirmative or negative is reliant upon whether there is a negative qualifier with the verb. These negative qualifiers are often: 不 or 没 (past tense).

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k6MNaOAxXSw

Take an example: If someone asks me if I went to school yesterday, and I didn’t, I’d respond: 昨天我没上学 (Yesterday, I didn’t go to school). If I did go to school, I’d respond 昨天我上学 without using the negative qualifier. Yet note, you aren’t responding in the affirmative or negative to the person’s question, but rather, to the verb in question.

While, simple enough to grasp in basic verb phrases, complications emerge when there are multiple verb-actions in question. For example, when managing my classrooms, I would have to micro-manage the other Chinese teaching assistants, giving them assignments, requests or copies to make. If I listed everything I wanted taken care of and then ask if they’d understand, I’d get a response with “yes” or OK.

Yet days later and much to my chagrin, I’d find the task incomplete or not even attempted to be carried out. I’d ask what happened, why hadn’t they done what I asked, to which I’d receive a response of just “No”. After switching over to and interrogating further in Chinese, I learned that my English wasn’t fully grasped, as they thought my demands were actually requests. Oh why did I teach them the power of “maybe”? See how questions can be asked with yes or no below:

Soon thereafter, I would translate my English to Chinese after giving a command, making sure I’d hear a concrete affirmative verb response as a response. Using phrases in Chinese like: “明白吗” or “is it clear”,and “对不对” or “correct or not” helps, but there is still always room for different interpretation.

The point is that “yes” and “no” are filler words for the Chinese, and don’t have a real meaning in common day language. They’re more of a parlor trick, often said much like a parrot repeating a phrase (often met with a blank stare or wide eyed look of confusion) to bring finality to a conversation. Yes.

Follow Steve on twitter: @seeitbelieveit

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

About the Author: Stephen

Writer and blogger for all things China related. Follow me on twitter: @seeitbelieveit -- My Background: Fluent Mandarin speaker with 3+ years working, living, studying and teaching throughout the mainland. Student of Kung Fu and avid photographer and documentarian.

Comments:

a:

Kinda like and English newsreader saying “allright” at the end of newspiece?

Mike:

great stuff , the only down is you only use simplified characters which not everyone is learning. As an informative article you could include both to accomodate all students of chinese language and literature.

Shannon Fabry:

LOVE this one. Thank you!!

Vivian Monica:

very very interesting blog…a language is more than learning words … can I receive this blog or any other previous blogs in my email?

thanks