The Hobbit as English Literature Posted by Gary Locke on Sep 21, 2017 in Culture

In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.

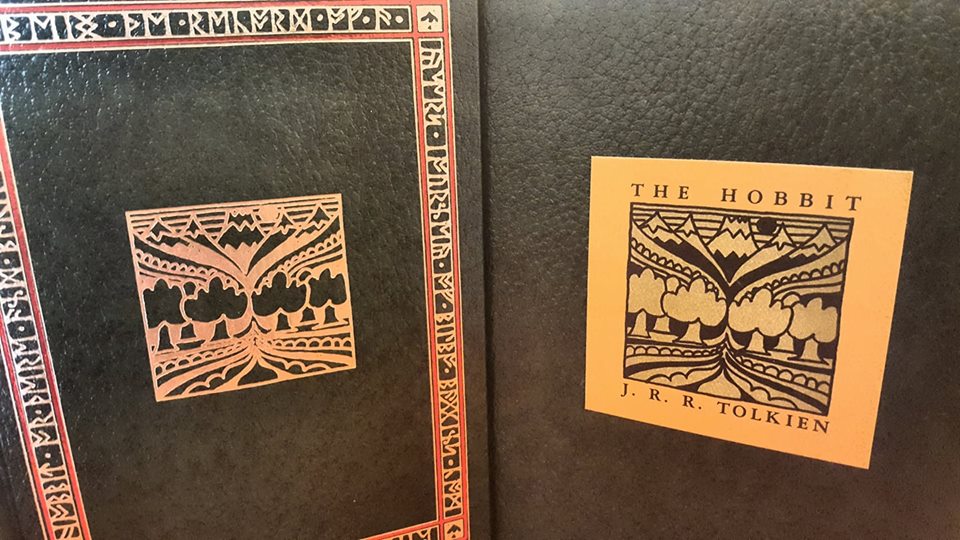

The Hobbit

On September 21, 1937, a book was published which would have a profound and lasting effect on popular culture. It spawned other books by the same author, books about those books by scholars and fans, and an astonishing series of films. More importantly, the book inspired other authors to take up their pens and write works of a similar nature. It was J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit, or There and Back Again.

The Hobbit is a tale of self-discovery for a seemingly simple hobbit named Bilbo Baggins. Bilbo is offered an opportunity to take a journey of adventure, something hobbits are not pre-disposed to do. A wizard named Gandalf and a coterie of Dwarves eventually persuade Bilbo that he is the catalyst to helping the Dwarves cross Middle Earth to The Lonely Mountain and rescue their ancestral treasure from the evil dragon, Smaug. Along the way, Bilbo encounters Wargs, Goblins, Elves, a giant spider, and an insanely murderous creature called Gollum, whom Bilbo curiously takes pity on. He collects a sword, some treasure, and a mysterious ring. Although reluctant, and always longing for the simple pleasures waiting for him back home, Bilbo learns to his amazement that he is resourceful, clever, and brave.

The Author

Tolkien was an academic scholar and don at Oxford University when, one night, he tired of grading papers and instead began to scribble down ideas for a novel for his children that would contain elements of a new kind of mythology. His title at Oxford was as the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon, which is an honorarium meaning that he was the university’s leading expert on early English literature, its traditions, and influences. He used his vast knowledge in this area to lovingly craft his magical tale.

Tolkien had, at the outset, a vague ambition to write a novel for his children which would embody the elements of Anglo-Saxon epics and myths, including Norse mythology and the early English saga of Beowulf. Like those tales, his story of Bilbo Baggins, and all the inhabitants of Middle Earth, began as oral narratives – bedtime stories! He recognized the significance of the heroic tradition in early cultures, and the power that myths and legends have in developing a culture.

In the 1920s, over a decade before the writing of The Hobbit, Tolkien set out to create a mythology for England, incorporating all the Anglo-Saxon, Celtic, and Icelandic beliefs and sagas combined with a deeply Christian moral system of good and evil. Although devoutly Catholic, his pre-history of English mythology never mentions God or Christ. Nevertheless, the precepts of his faith can be found throughout the work. He never abandoned this project, continuing to expand on it for over half a century until its eventual publication shortly after his death as The Silmarillion.

Tolkien loved languages. He was adept in creating new ones based on runes, the ancient northern system of writing, and dialects from throughout the Anglo-Saxon world. His names for many of the characters and locations in The Hobbit and in The Lord of the Rings are totally invented, but they sound authentic. As the stories grew more complex, so did his invented languages. They contain a grammatical symmetry and cohesion which is quite remarkable.

Roads Go Ever, Ever On

Given the work that he had already put into his mythology, and his broad knowledge of linguistics and the history of literature, it’s easy to see how Tolkien could amalgamate all of this into bedtime stories for his children. Finally, he set them to paper in one story.

He offered an early draft to several colleagues (more on them later) and at least one student, Elaine Griffiths, who in turn showed it to a friend then working for the publisher Stanley Unwin. Unwin, so the story goes, paid his young nephew to read the book and only agreed to publish it based on the boy’s enthusiastic reaction.

Tolkien also belonged to a society at Oxford called The Inklings, a group of academics who gathered at the Eagle and Child pub during semester to drink beer and discuss literature and academia. He passed the book around at one of these sessions, and it eventually fell into the hands of Tolkien’s friend, CS Lewis. He was so affected by Tolkien’s ability to charm young people with a deceptively complex idea, that Lewis went on to write his own allegorical saga of Christian philosophy, The Chronicles of Narnia.

Today, of course, we have JK Rowling’s novels of the young wizard Harry Potter, and many other works of fantastic literature, all of which owe some of their inspiration to the complex world which Tolkien crafted from his brilliant mind and stunning imagination.

Of course, it’s easy to enjoy The Hobbit without spending any time at all thinking about its literary, historical, or linguistic origins. It’s a charming tale of wizards, dragons, elves, and adventure. It appealed to children, which was certainly Tolkien’s intent, and even included some simple poems which anyone could relate to. It isn’t a fussy, stuffy book at all. It is, rather, a crackling good yarn!

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

Janet:

I love this article. =-)