Esperanto Filmoj and the “New Esperanto” Posted by Leks on Sep 26, 2015 in Uncategorized

Have you ever heard of the film production company Esperanto Filmoj? You might recognize it from its affiliation with the prominent directors Guillermo del Toro (of Pan’s Labyrinth fame, which Esperanto Filmoj helped make), and Alfonzo Cuarón (the man behind Gravity and Children of Men, as well as the owner of Esperanto Filmoj). Its name is slightly misleading, as it has not yet produced any films in Esperanto – which you may have guessed from the grammatically inaccurate name! It has, however, financed both English and Spanish productions, so the company does support linguistic diversity, like any good Esperanto organization should.

I bring up Esperanto Filmoj today because the origin of its name offers some interesting food for thought. It lies in a remark Guillermo del Toro once made about cinema. A 2007 article on Pan’s Labyrinth in La Vanguardia [please note that’s it in Spanish] credits del Toro with the remark, “El cine es el esperanto del mundo actual” – roughly translated, “Cinema is the Esperanto of the modern world.” Cuarón must have found something appealing in that sentiment. In an interview with documentarian Sam Green (maker of a short documentary on Esperanto, The Universal Language), Cuarón reveals that, while he is not an Esperantist himself, he is sympathetic toward the aims and attitude of Esperanto. Calling his production company Esperanto Filmoj, then, is at once a gesture of respect for the language, and a tacit suggestion that film can do the work Esperanto initially set out to accomplish.

I have to wonder whether del Toro and Cuarón aren’t on to something. If anybody can be called an authority on breaking the language barrier, either of these directors could be fine candidates – their films have seen wide international releases, and won numerous international awards in the process. Assuming that cinema could be “the Esperanto of the modern world,” what exactly gives it that status? In other words, what does the cinema do that lets it act like a universal language?

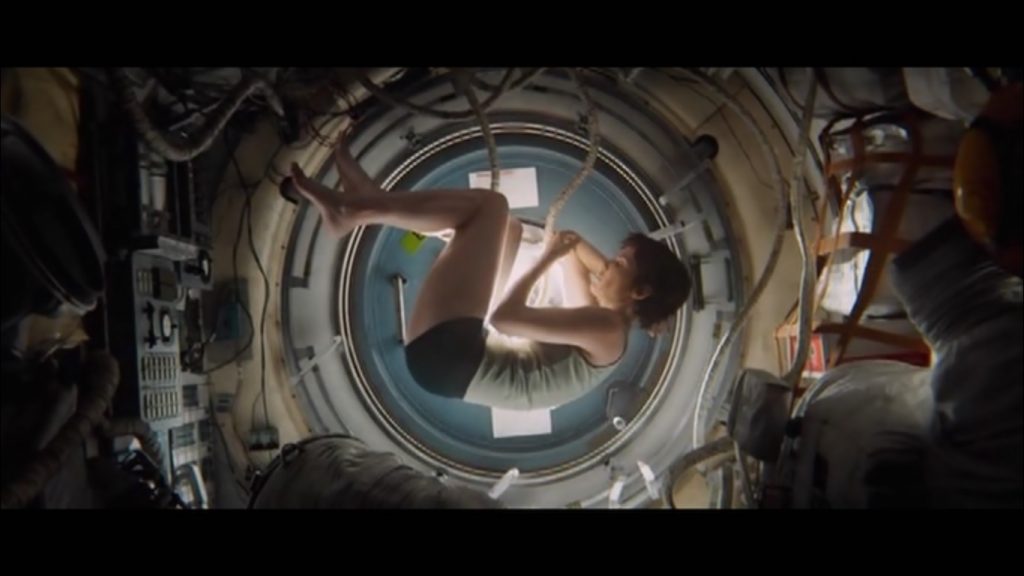

One possibility is that, because the cinema works using pictures, it operates on a level distinct from verbal language. In most instances, people learn how to see before they learn how to speak. We’re visual beings before we’re linguistic beings. Perhaps the cinema taps into this, and relies on a level of human experience that doesn’t require language. After all, many of the most powerful moments in cinema history are not the result of spoken lines, but of astonishing visuals. Consider this still from Cuarón’s Gravity:

You may not need to understand any of the world’s languages to grasp the emotions and poetry of this scene. The actress’s (Sandra Bullock’s) posture lets you know this is a moment of both vulnerability and comfort. The fetal position she’s curled into – made all the more striking by the wires behind her that resemble an umbilical cord – make her look defenseless, but show her within the shielding confines of the space station, which relaxes and guards her the way a mother might her child. No narration – and no subtitle – is required to convey all that.

If Esperanto was an invention created to breach linguistic barriers, then perhaps cinema is the next step up in the evolution of that invention. Much in the same way that we keep inventing new means of transportation, we might keep developing new technologies of interlingual communication. Maybe cinema is one of those technologies. I wonder what will come after it, and how effective it will be?

What do you think of del Toro’s and Cuarón’s ideas regarding Esperanto and cinema? (Or mine, for that matter…?) Sound off in the comments.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

Herman D.:

Stromae, one of the most popular contemporary singers in Europe singing in French, has taken the risk to give concerts in the very protective Anglo-American music market, where it is very hard to succeed if songs are not in English. Singing there ‘French only’ is what no other French singers did before. He is making a statement by saying that ‘it would sound like an imitation if I would sing my songs in English’. The success in the UK and the US of one of his most favourite hits “Alors on dance” has convinced him that people don’t have to understand the language to feel and like the music. Moreover, that kind of acceptation by the audience showed that it is possible to create a cultural and lingsuistic openness that can offer singers in a foreign language the same level playing field as for American acts e.g., something Stromae appreciates very much.

Datan0de:

Lovely article. I’d always wondered what the connection was between Esperanto Filmoj and the Esperanto language.

I do think that it’s a pity that more movies, particularly sci-fi movies, don’t incorporate Esperanto as a “background language” as was done in Blade Trinity (and Gattica to a lesser extent). It’s an easy way to give a setting a foreign feel without tying it to any particular locale.