Commemorating the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre Posted by Rachael on Apr 14, 2019 in Hindi Language

This past Saturday, April 13th, marked the 100th anniversary of the massacre (हत्याकांड/hatyaakaand) at Jallianwala Bagh (जलियांवाला बाग़, baag=garden) that occurred on this date in the year 1919. It was in this public garden (बाग़/baag, बग़ीचा/bageechaa) in Amritsar (in the then-province of Punjab) that General Reginald Dyer, an officer in the British Indian Army, directed his men to open fire on unarmed Indians who had gathered there to celebrate the Sikh New Year. This tragic event resulted in 379 deaths (मौत/maut) and over a thousand people injured (घायल/ghaayal). As historians (इतिहासकार/itihaaskaar) have noted, this was a momentous event, as it helped catalyze further the fight for Indian independence (भारतीय स्वतंत्रता/bhaaratiya svatantrataa) that had been building steadily over the past several decades.

General Dyer’s decision to open fire on peaceful civilians (नागरिक/naagrik) was partly informed by hostilities and mistrust between the Indians and the British that had only grown since the Great Rebellion of 1857. During this Rebellion, Indian sepoys of the British Indian army (सेना/senaa) and others who resented the unjust imposition of British power rebelled against the East India Company, resulting in the demise of several Europeans and substantially weakening the company’s authority (अधिकार/adhikaar) in North India. Although the British roundly defeated the rebels, as they had greater resources to do so, this traumatic event sowed the seeds of a widespread and deeply ingrained paranoia and anxiety amongst them: the rebels had made blatantly clear that the British were unwelcome and, in light of that, another rebellion was almost certain to occur. To attempt to discourage this from happening, the British enacted extremely restrictive laws (कानून/kaanoon) to bolster their authority over the subject population, as I will explain below. And, in 1859, the British crown took control of India as its colony, hoping that the authority of the crown would govern with a steadier hand than a corporation.

Examples of the aforementioned restrictive legislation include the Defense of India Act of 1915 which, enacted under the guise of bolstering security during WWI, gave the colonial government (सरकार/sarkaar) the power to jail (गिरफ़्तार करना/giraftaar karnaa=to arrest) people without a trial as a “preventative measure” and limit civilians’ freedom to speak, write and move about as they chose. After the war (युद्ध/yuddh, जंग/jang) ended, the anxieties of the colonial regime only grew, which led to the passage of the Anarchical and Revolutionary Crimes Act (known as the Rowlatt Act), which extended the wartime emergency measures mentioned above to peacetime. According to this law, it was illegal for Indians to gather in a public place, even if these gatherings were peaceful, as such “unauthorized” assemblies were suspected of breeding sedition.

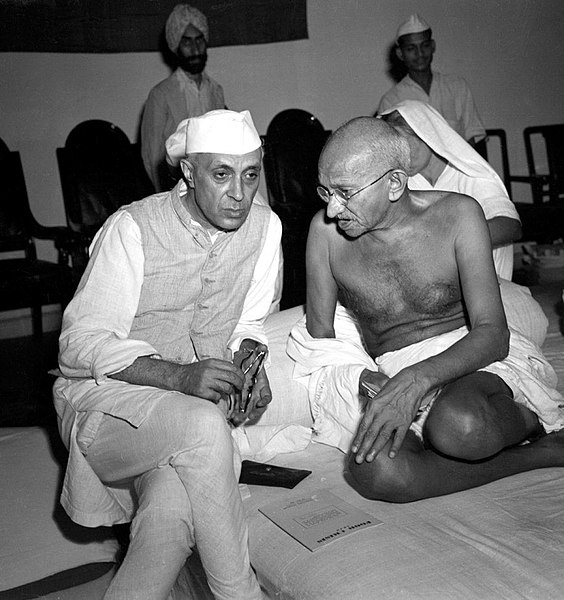

Even Gandhi, who had supported England’s cause in WWI, was vehemently opposed to the passage of the Rowlett Act and called for a nationwide, nonviolent strike (or satyagraha/सत्याग्रह) on April 6, 1919, which involved fasting (उपवास रखना/upvaas rakhnaa) for a day and organizing meetings to argue for the repeal of the law. Clearly, Gandhi was not the only powerful figure who had publicly declared his opposition (विरोध/virodh) to the increasingly restrictive measures imposed by the British. The colonial power was especially on edge when it came to the Punjab as, even before Gandhi voiced his opposition to the Rowlett Act, Punjabi nationalist leaders had repeatedly shown their displeasure with the British regime. The British, for whom the Punjab was a valuable resource (संसाधन/sansaadhan) – providing much of the nation’s agricultural products and a large number of the British Indian army’s soldiers – were wracked with anxiety that the Punjab may turn against them.

On April 10th, Gandhi announced (ऐलान करना/ailaan karnaa) that he was going to travel to the Punjab to support nationalist leaders who were protesting (विरोद करना/virod karnaa) the enactment of the Rowlett Act, but the British stopped his train and arrested him. In response to this, protestors (प्रदर्शनकारी/pradarshankaari) in Amritsar fought with authorities, which led to the deaths of at least ten Indians. As the situation continued to escalate, the crowd of protestors vandalized government property, set two banks ablaze, killed five Europeans and attacked Marcella Sherwood, a European missionary. In response to this increasingly dire situation, General Dyer was assigned to take control of Amritsar on April 11th. In an effort to extinguish rising tensions, he announced that all public assemblies were prohibited and threatened that, if this order were defied, such an assembly would be met with force. Subsequently, when a British commission was appointed to investigate potential wrongdoing in the massacre that later occurred, Dyer admitted that his “aim was not to disperse the crowd (भीड़/bheer) but to produce a ‘moral effect.'” He never went to jail, nor was punished formally in any way for his actions, although he was dismissed from service after this incident.

Shockingly, when news (ख़बर/khabar) of the massacre arrived in Britain, many there justified Dyer’s actions as essential to controlling the subject population. Indeed, to this day, no member of the British government or royal family has ventured to make a formal apology (माफ़ी/maafi) for this particularly cruel episode in India’s colonial past. But for Indians, this event spurred the complacent to action and strengthened the convictions of those who already considered themselves nationalists (राष्ट्रवादी/rashtravaadi) in their fight for India’s independence. It was now abundantly clear that the British Raj was not interested in “fair” and “reasoned” governance but was intent on exercising its authority by any means necessary, no matter the dire consequences (नतीजा/nateejaa).

You can still visit Jallianwala Bagh today, where a memorial to those slain has been erected. Although this was among the most traumatic and bloody episodes in India’s colonial history, those who died did not do so in vain; rather, their deaths exposed the colonial regime as callous and inherently unjust and thus inspired a forceful recommitment to the cause of Indian independence, which was finally achieved in 1947.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

ADITYA KASHYAP:

Bahut hi badiya post sir ji aapke ke post ki picture Quality bahut accha hai