Sahir Ludhianvi: A Poet of the Silver Screen (Part 2) Posted by Rachael on Oct 14, 2017 in Hindi Language, Uncategorized

If you haven’t already, check out my part 1 of this series on the talented poet and lyricist, Sahir Ludhianvi, and enjoy this part 2 on his work and literary style!

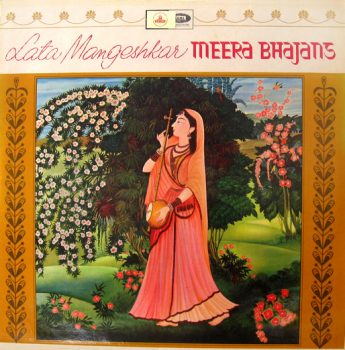

Although Ludhianvi is perhaps best known for his role as a film lyricist, his poetry beyond that certainly commends itself. He made his debut as a film lyricist in Bollywood with the film Azadi ki Raah Par/आज़ादी की राह पर (On the Path of Freedom, 1949), but the film and the songs proved unremarkable. In 1951, while working with the famed music director S. D. Burman/सचिन देव बर्मन, Ludhianvi finally gained acknowledgement for his work on the songs of Naujawaan/नौजवान (A Youth). To this day, Ludhianvi is also fondly remembered as the lyricist for the film Pyaasa/प्यासा (Thirsty or Longing), with its subversive themes and beautiful music. Although he was infamous for being difficult to work with (some of his many “primadonna-esque behaviors” included insisting that the music of a film be composed for his own lyrics not vice versa and his demand that he be paid one rupee more than Lata Mangeshkar/लता मंगेशकर, a famous Hindi playback artist), he was a remarkable poet and was thus forgiven for many of his petty transgressions.

While reading his verse, one is impressed by a sense that he is certainly before his time and stands out amongst his contemporaries as extremely unconventional. Unlike other poets and writers of the time, he does not express a passionate love for God (ख़ुदा/khudaa) and does not seem obsessed with earthly beauty (हुस्न/husn) or wine (जाम/jaam), common tropes in Urdu poetry. His verse conveys somewhat of a bitter tone and is often a lamentation of the corruption and lack of morality that reigns in society, the pettiness and arbitrary nature of war and politics and the rise of consumerism as capitalism slowly took its hold over India, replacing genuine emotional connections between people. In addition, his verse on love usually does not have a sunny outlook—it generally references unrequited or otherwise defeated love and, in the background of such verse, is the urgent epiphany that there are many other issues in the world more important to write about than love.

Even today, many consider him the “bard of the underdog” in that he stood up for the poor, the disadvantaged, the exploited and the oppressed from many sections of society. His songs of social justice abound, but especially in the aforementioned film Pyaasa, one particular song reaches out to viewers, in an excoriating lamentation of the decay of modern Indian society: जिन्हें नाज़ है हिंद पर, वह कहाँ है? (Jinhe naaz hai Hind par, voh kahan hai/Where are those who take pride in India?). Like his fellow poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz/फ़ैज़ अहमद फ़ैज़ (1911-1984), Ludhianvi injected modern Urdu poetry with heady intellectualism and social satire aimed squarely at those who stood to profit the most from the exploitation of the poor and disadvantaged, such as powerful politicians, manipulative and egotistical religious leaders, wealthy businessmen and aggressive nation states. In the context of post-Independence India and the partition of Pakistan from India, Ludhianvi urged the public to realize that, despite the achievements that independence entailed, the fight for justice was long from over.

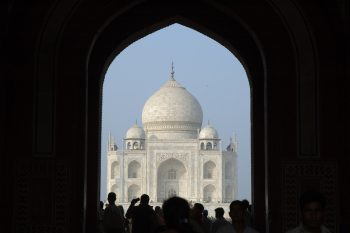

One of Ludhianvi’s most celebrated poems, “Taj Mahal/ताज महल/تاج محل” (from the 1964 film Gazal/ग़ज़ल/غزل), is named after the Mughal Empress Mumtaz Mehel’s tomb that still stands today in Agra; the mausoleum was commissioned by her husband, Emperor Shah Jahan, in 1632. As his favorite wife, Shah Jahan commanded the construction of this tomb as a tribute to her memory and a symbol of his undying love for her. She died in the throes of childbirth, after giving birth to their 14th child. Although many see the Taj Mahal as one of the most visible and splendid constructions that attests to the magnificence and power of the Mughal Empire (which lasted roughly from 1526 to 1857) and the richness of India’s history, Ludhianvi, as usual, takes a different view of this celebrated tomb:

|

Urdu Text |

English translation |

Hindi Text and Roman Transliteration |

|

تاج تیرے لیے اک مظہر_الفت ہی سہی |

For you (the beloved), it is fitting that the Taaj (lit. means “crown,” “crest” or “paragon”) be an expression of love |

ताज तेरे लिए इक मज़हर-ए-उल्फ़त ही सही (Taaj tere liye ik mazhar-e-ulfat hi sahi) |

|

تجھ کو اس وادیٴ_رنگیں سےعقیدت ہی سہی |

Your (the beloved’s) devotion to this colorful valley is suitable |

तुझको इस वादी-ए-रंगीन से अक़ीदत ही सही

(Tujhko is vaadi-e-rangeen se aqidat hi sahi) |

ﷺ |

||

|

میری محبوب، کہیں اور ملاکر مجھسے |

(Yet) My love, meet me somewhere else |

मेरी महबूब, कहीं और मिलाकर मुझसे

(Meri mehboob, kahin aur milaakar mujhse) |

|

بزم_شاہی میں غریبوں کا گزر کیا معنی؟ |

What does the passing of the poor mean in the royal assembly? |

बज़्म-ए-शाही में ग़रीबों का गुज़र क्या मअ’नी?

(Bazm-e-shaahi me gareebon kaa guzar kyaa ma’ani?) |

ﷺ |

||

|

شبت جس راہ میں ہوں سطوت_شاہی کے نشاں |

What do the travels of passionate souls mean… (this and the line below it are switched) |

सब्त जिस राह में हों सतवत-ए-शाही के निशान

(Sabt jis raah me hon satvat-e-shaahi ke nishaan) |

|

اس پے الفت بھری روحوں کا سفر کیا معنی؟ |

On the path inscribed with the signs of imperial power? |

उस पे उल्फ़त भरी रूहों का सफ़र क्या मअ’नी?

(Us pe ulfat bhari roohon kaa safar kyaa ma’ani?) |

ﷺ |

||

|

میری محبوب، پس_پردہ_تشہیر_وفا |

My love, behind the public veil of constancy |

मेरी महबूब, पस-ए-पर्दा-ए-तश्हीर-ए-वफ़ा

(Meri mehboob, pas-e-pardaa-e-tashheer-e-vafaa) |

|

تونے سطوت کے نشانوں کو تو دیکھا ہوتا |

You must have seen the signs of power |

तूने सतवत के निशानों को तो देखा होता

(Toone satvat ke nishaanon ko to dekhaa hotaa) |

ﷺ |

||

|

مردہ شاہوں کے مقابر سے بہلنے والی |

You must have seen your own dark houses, (this and the line below it are switched) |

मुर्दा-शाहों के मक़ाबिर से बहलने वाली

(Murdaa-shaahon ke maqaabir se behelne vaali) |

|

اپنے تاریک مکانوں کو تو دیکھا ہوتا |

That distracted you from the graves of dead kings. |

अपने तारीक मकानों को तो देखा होता

(Apne taareek makaanon ko to dekhaa hotaa) |

ﷺ |

||

|

ان گنت لوگوں نے دنیا میں محبت کی ہے |

Countless people have loved in this world, |

अन-गिनत लोगों ने दुनिया में मोहब्बत की है

(An-ginat logon ne duniyaa me mohabbat ki hai) |

|

کون کہتا ہے کہ صادق نہ تھے جذبے انکے |

Who’s to say that their emotions were not sincere? |

कौन कहता है कि सादिक़ न थे जज़्बे उनके

(Kaun kehtaa hai ki saadik na the jazbe unke) |

ﷺ |

||

|

لیکن انکے لیے تشہیر کا سامان نہیں |

But they did not possess the means of publicizing their love |

लेकिन उनके लिए तश्हीर का सामान नहीं

(Lekin unke liye tashhir kaa saamaan nahin) |

|

کیوںکہ وہ لوگ بھی اپنی ہی طرح مفلس تھے |

Because those people too were poor in their own way |

क्योंकि वह लोग भी अपनी ही तरह मुफ़्लिस थे

(Kyoonki voh log bhi apni hi tarah muflis the) |

ﷺ |

||

|

یہ عمارات و مقابر یہ فصیلیں یہ حصار |

These monuments and graves, these ramparts, these fortresses |

ये इमारत-ओ-मक़ाबिर, ये फ़सीलें, ये हिसार

(Ye imaarat-o-maqaabir, ye faseelen, ye hisaar) |

|

مطلق اولحکم شہنشاہوں کی عظمت کے ستوں |

They are the pillars that attest to the glory of the Emperor’s (lit. “King of Kings”) absolute rule |

मुतलक़-उल-हुक्म शहंशाहों की अज़्मत के सुतूँ

(Mutlak-ul-hukm shehenshaahon ki azmat ke sutuun) |

ﷺ |

||

|

سینہٴ_دہر کے ناسور ہیں کہنہ ناسور

|

In the bosom of the earth, there are festering wounds, ancient wounds |

सीना-ए-दहर के नासूर हैं कोहना नासूर

(Seenaa-e-deher ke naasoor hain, kohnaa naasoor) |

|

جذب ہے ان میں تیرے اور میرے اجداد کا خوں |

Those wounds have absorbed the blood of our ancestors |

जज़्ब है उनमें तेरे और मेरे अज्दाद का ख़ून

(Jazb hai unme tere aur mere ajdaad ka khoon) |

ﷺ |

||

|

میری محبوب، انہیں بھی تو محبت ہوگی |

My beloved, they too must have loved |

मेरी महबूब, उन्हें भी तो मोहब्बत होगी

(Meri mehboob, unhe bhi to mohabbat hogi) |

|

جن کی صناعی نے بخشی ہےاس شکل اے جمیل |

Those whose craftsmanship bequeathed to this (the Taj) an architectural feat (lit. “beautiful appearance”) |

जिन की सन्नाई ने बख़्शी है उसे शक्ल-ए-जमील

(Jin ki sannai ne bakshee hai use shakl-e-jameel) |

ﷺ |

||

|

انکے پیاروں کے مقابر رہے بنام و نمود |

The graves of their loved ones remain nameless, without pomp |

उनके प्यारों के मक़ाबिर रहे बेनाम-ओ-नुमूद

(Unke pyaaron ke maqaabir rahe benaam-o-numood) |

|

آج تک ان پے جلائ نہ کسی نے قندیل

|

To this day, no one has lit a candle for them |

आज तक उनपे जलाई न किसी ने क़िंदील

(Aaj tak unpe jalaai na kisee ne qindeel) |

ﷺ |

||

|

یہ چمن زاریہ جمنا کا کنارہ یہ محل |

This verdant meadow, this palace on the banks of the Yamuna (a river) |

ये चमन-ज़ार, ये जमुना का किनारा ये महल

(Ye chaman-zaar, ye jamunaa kaa kinaaraa ye mehel) |

|

یہ منقش در و دیوار یہ محراب یہ طاق |

These gilded doors and walls, these arches, these niches |

ये मुनक़्क़श दर-ओ-दीवार, ये मेहराब, ये ताक़

(Ye munaqqash dar-o-deevaar, ye mehraab, ye taak) |

ﷺ |

||

|

اک شہنشاہ نے دولت کا سہارا لےکر |

A King of Kings, with the help of wealth, |

इक शहंशाह ने दौलत का सहारा लेकर (Ik shehenshaah ne daulat kaa sahaaraa lekar) |

|

ہم غریبوں کی محبت کا اڑایا ہے مذاق |

Turned the love of (us) the poor into a joke |

हम ग़रीबों की मोहब्बत का उड़ाया है मज़ाक़

(Ham gareebon ki mohabbat kaa uraayaa hai mazaak) |

ﷺ |

||

|

میری محبوب، کہیں اور ملاکر مجھسے |

My love, meet me somewhere else |

मेरी महबूब, कहीं और मिलाकर मुझसे

(Meri mehboob, kahin aur milaakar mujhse) |

Lastly, here’s the performance of this poem (sung by the great playback singer, Mohammed Rafi) from the film Ghazal, for which Ludhianvi originally wrote it:

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.