Figures from Hindi Literary History: Shivrani Devi Premchand Posted by Rachael on Jan 12, 2019 in Hindi Language

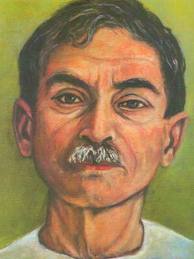

Although many acquainted with the Hindi literary world (हिंदी साहित्यिक क्षेत्र/Hindi saahityik kshetra) are familiar with the name Munshi Premchand/मुंशी प्रेमचंद (his real name was Dhanpat Rai Shrivastav), a prolific author (लेखक/lekhak) who expressed his passion for social justice (सामाजिक न्याय/saamaajik nyaay) in his fiction, many people may not be familiar with his wife, Shivrani Devi Premchand/शिवरानी देवी प्रेमचंद (1894-1976), although her life is no less interesting than that of her husband and her literary and social contributions no less compelling. She, too, made her mark on the literary world with short stories (कहानियाँ/kahaaniyaan or लघु कथाएँ/laghu kathaae) that she published in women’s magazines of the day, but perhaps her crowning achievement is her memoir of her husband, entitled प्रेमचंद घर में (Premchand at Home). Despite its stated purpose as a memoir (जीवन चरित्र/jeevan charitra or संस्मरण/sansmaran) of her husband’s life and works, Shivrani Devi reveals a lot about herself and her relationship with her husband, especially concerning their home life, in the memoir, so much so that it may rightly be termed an autobiography. Through examining Shivrani Devi’s memoir, we come to appreciate even more the literary giant that was Premchand but also learn about the contributions of his wife and those of women like her who are not often celebrated in traditional historical records (पारंपरिक ऐतिहासिक अभिलेख/paaramparik aitihaasik abhilekh).

In Shivrani Devi’s memoir, she introduces us to herself by stating her father’s name, Munshi Deviprasad (मुंशी is a title given to a learned man or scribe of the time), and the specific location of her natal home in the United Provinces (now Uttar Pradesh/उत्तर प्रदेश): Fatehpur (फतेहपुर) district, Salimpur (सलीमपुर) village, Kanvar (कनवार) post office. Her father, a relatively prosperous zamindar/जमींदार (landlord), married her off at the age of 11. Through her description of this event, it seems less than momentous for the young Shivrani as she does not remember when it occurred or even when she was widowed. In fact, she remembers only that the marriage lasted 3-4 months before her husband passed away. Fortunately, Shivrani seems to have had an especially close and loving relationship (रिश्ता/rishtaa) with her father. Through this bond and her father’s resultant desire to see her happy (“वे…मुझे सुखी देखना चाहते थे” (PGM 29), she was able to escape the misery of perpetual widowhood (विधवापन/vidhvaapan), which so many other Hindu widows (विधवा/vidhvaa) at this time had to endure, as her father set about arranging a second marriage for her.

According to scholar Jyoti Atwal, Shivrani’s father arranged her second marriage by writing and publishing a book in 1905 called Kayasth Bal Vidhva Uddharak Pustika or कायस्थ बाल विधवा उद्धारक पुस्तिका (A Book for the Deliverance of Kayasth Child Widows) in which he included an advertisement (विज्ञापन/vigyaapan) for the remarriage of his daughter (Atwal 1632). Shivrani’s caste/जाति (she was a kayasth, which is a scribe caste generally regarded as Kshatriyas, or one of the three twice-born castes) is referred to in the title of her father’s book. Fortunately, Premchand saw this advertisement and wrote to Shivrani’s father, stating his desire to marry as well as his educational qualifications (शिक्षात्मक योग्यताएँ/shikshaatmak yogyataae) and salary (वेतन/vetan). The two men arranged to meet in Fatehpur and, as Shivrani’s account goes, Premchand made a favorable impression on her father and he agreed to sanction the marriage.

Shivrani speaks of Premchand’s decision (फैसला/faislaa) to marry her, a child widow (बाल विधवा/baal vidhvaa), with evident pride when she states that, “your aunt’s [actually Premchand’s stepmother] opinion, etc., was not consulted in our marriage. But this was your daring. You wanted to break off your ties to society to the point that you didn’t give the news even to your relatives” (“मेरी शादी में आपकी चाची वग़ैरह किसी की राय नहीं थी । मगर यह आपकी दिलेरी थी । आप समाज का बंधन तोड़ना चाहते थे । यहाँ तक कि आपने अपने घरवालों को भी ख़बर नहीं दी,” PGM 29). This was indeed a bold and unusual move on Premchand’s part, most likely influenced by Premchand’s reformist social beliefs and the fact that his father had married him off previously when he was only a teenager, which remained a bad memory to him; in fact, he was still married at the time of his marriage to Shivrani, which she did not discover until later (Lal 15).

Shivrani learned to read, write and cultivate an appreciation for literature (साहित्य/saahitya) through her husband’s tutorials and his recitations of his own work, criticism of his work and newspapers (अख़बार/akhbaar) in multiple languages (including English, which he extemporaneously translated into Hindi for her benefit). Inspired by her husband and her own desire to challenge herself in the arenas of reading and composition, Shivrani’s literary work was published for the first time in 1924 in the form of a story, “Sahas/साहस” (“Courage”); this story appeared in a well-known women’s journal of the time, called “Chand/चाँद” (“Moon”) (Atwal 1632).

Later, Shivrani would go on to write a full-length memoir of her husband, which would be published in 1944 in the midst of the Progressive Writer’s Movement, which began in Lucknow in 1936. During this movement, “literary intellectuals revisited and reworked their political associations and ideological commitments,” often bringing controversial social issues to the fore of their writing (Atwal 1635). This movement and the ideologies it espoused may have influenced Shivrani to state boldly her progressive stance on certain social issues (सामाजिक मुद्दे/saamaajik mudde) primarily affecting women and craft a memoir about her literary husband with such a strong imprint of her own personality (व्यक्तित्व/vyaktitva) and experiences (अनुभव/anubhav) (Atwal 1635).

In the memoir’s many vignettes, Shivrani relates her adventures and travails as the leader of a woman’s ashram (महिला आश्रम) during the Independence Movement (स्वतंत्रता आंदोलन/svatantrataa aandolan) and her subsequent sojourns in jail in the service of this movement. She tells the reader that she assumed the responsibility (ज़िम्मेदारी/zimmedaari) of going to jail, despite Premchand’s concurrent involvement in the movement, as she was healthier while Premchand often suffered from ill health and would have fared poorly in prison. Thus, Shivrani’s activism was decidedly “participatory,” as opposed to Premchand’s “literary activism” (Atwal 1631). Although Shivrani Devi’s memoir was often overlooked in scholarship on Premchand, it is now being recognized by more and more scholars of the great literary figure and those who wish to study Shivrani Devi as a fascinating historical figure in her own right.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

mrinalini watson:

Hi Richa,

Love your posts. This is the only blog I read at present. 🙂

By the way, did you happen to study at AIIS in Jaipur?

Rachael:

@mrinalini watson बहुत शुक्रिया! आपका नोट पढ़कर बहुत ख़ुशी हुई 🙂 Yes, I did study at AIIS Jaipur!