Stumbling Through Strong Masculine Nouns, Or: There’s More Than One Good Way To Decline Posted by Meg on Jan 25, 2017 in Icelandic grammar

Today I’d like to introduce you to a new noun class. They’re generally called “strong” nouns, or masculine, feminine, and neuter II and III. I’m just going to go into masculine II and III nouns today. Fair warning: it’s a little dry.

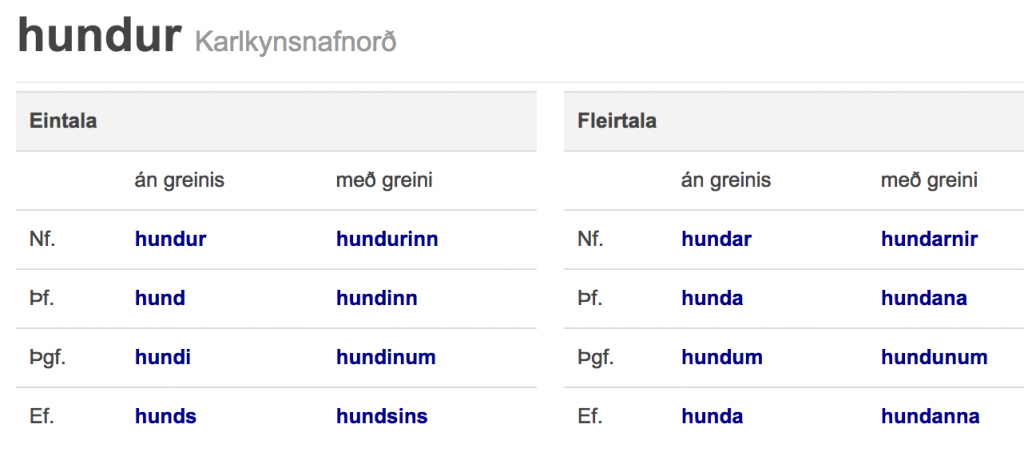

So the declension pattern you’ve likely seen so far is follows nouns like hestur or hundur for masculine nouns, mynd or stelpa for feminine, and hús for neuter nouns.

The first thing to know about class II and III nouns is that the nominative and accusative plural endings will change. That’s the takeaway, I think.

Masculine nouns ending in -ur (as written in the kennimynd or dictionary entry) will have an -ir ending in the nominative plural instead of an -ar ending. IMPORTANT: the definite articles do not change.

The accusative plural will simply be -i instead of -a. Examples include gestur (guest), fundur (meeting), glæpur (crime), hvalur (whale), and vinur (friends). They´re hard to spot, so it´s best to simply learn them.

So instead of saying vinar, you´d say vinir. If you´re going to the movies with your friends, you´ll go with vini instead of vina.

There’s also often a B-vowel shift/stem change, or a B-víxl, in masculine type II nouns. It’ll follow one of these patterns:

- a) ö – e – a

- b) jö – i – ja

You’ll see this vowel shift in words like fjörður, þröstur (crow), and björn. [Also note that sonur is a type II masculine noun, but the vowel change is o — y.]

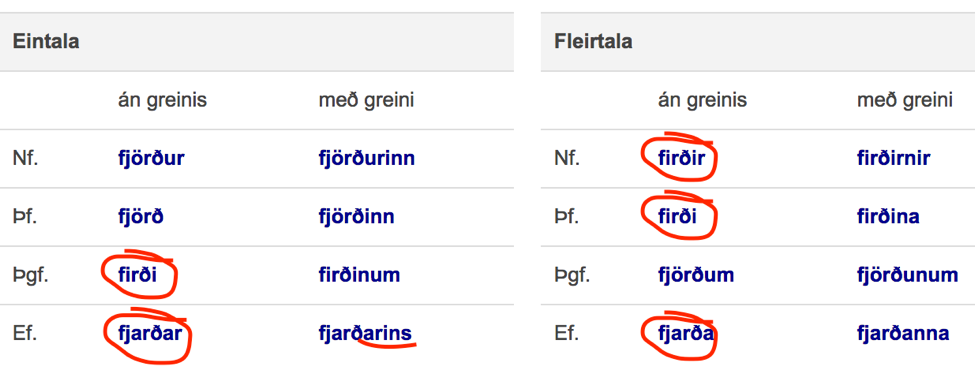

So the declension of fjörður — and similar words (incl. hjörtur and kjölur) — is:

Note that the initial vowel/stem change occurs in the dative (þágufall or “þgf”) singular. It is complicated, and largely a matter of memorization. But that’s a good starting point. You know that the nominative and accusative singular forms will be “normal,” they’ll reflect the dictionary entry.

So: you know that the stem change will happen in dative, and that the nominative and accusative plural forms will have the same stem change/vowel as the dative singular. You also know that the genitive plural and genitive singular have the same stem (vowel) — “a”.

Phew.

Last thing to note here:

You’ve probably come across the -ar-ins ending (vs s-ins) in the genitive singular. That’s a class II masculine form! If it has an -ir in plural, it’ll have an -ar-ins ending in the possessive (genitive) singular form. Generally. Most often.

BUT THERE IS MAYBE A SORT OF TRICK TO THIS MADNESS!

Masculine nouns ending in aður and uður are all always class III!

So we’re talking about words like mánuður, hönnuður, klæðnaður.

Lets have a look. What you need to know:

- They’ll always end in:

- -ir in nominative plural.

- -i in accusative plural (remember, we’re not talking about the definite article, which doesn’t change).

- They’ll end in -ar in genitive singular (so: -ar-ins).

- They’ll have an –i affixed to the stem in the dative singular (image below).

Similiarly, masculine nouns ending with –andi are type III.

Nouns ending in -andi denote a type of person or occupation — þýðandi [translator], nemandi [student]. They’ll decline like weak nouns in the singular. Nothing too tricky. They’ll have a vowel/stem change when going from singular to plural (a — e) and they’ll end in -ur in plural nominative and accusative.

Other type III nouns include:

- Nouns ending in –r (hver [hot spring], skjár [screen]) will end in -ir in plural nom and accu.

- Nouns like bóndi (farmer) and frændi (uncle/cousin), end in –ur in plural nom and accu.

- Bóndi has a stem change (ó — æ) that stays in place in all plural forms.

You can always look up declensions on bin.arnastofnun.is if you’re not sure. Check “Leita að beygingarmynd” to broaden your search (e.g., if you only know a declined form…).

If you’d like to provide some feedback on my first real grammar entry, please leave it for me in the comments! I know this entry was a bit dry, and I’m happy to hear ways to spice it up. Unfortunately, this particular facet of Icelandic grammar is largely memorization (less so in the case of -andi, –uður, and -aður.)

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

Alexandra:

I am in the UK and trying very hard to learn Icelandic. It’s really helpful to have a blog which gives grammar help, it’s very supportive so thank you. And keep these helpful posts coming!

Although every time I think I have learned something in Icelandic, I then find there is another facet to the grammar which I hadn’t realised…hopefully one day I will get there!

Many thanks, Alexandra.

Helen:

I too am struggling along with Icelandic by myself. Luckily there are lots of ways to get help online. I enjoy this blog because it provides very good explanations and often I see the light about a certain point. This article is especially helpful to me because it brings together the main things to consider and learn about a specific point in grammar. Finding ways to practise is more complicated. I use face book open groups (in my case about knitting) to be able to chat about my hobby with Icelandic people.

Thank you Meg for your help. Helen.