Would You Rather Kiss a Troll or an Elf? Posted by Meg on Jan 31, 2018 in Icelandic culture

When talking about Iceland, elves and trolls inevitably come up. When I went home over Christmas, I brought my mother jólasveinar (Jól – Christmas or yule + sveinn – plural – meaning boy or lad) collectables (I admit, I bought them at the airport) because she just loves those peculiarities of Icelandic culture. At the gate, while waiting to board the plane, a little American girl and her mother were debating whether or not the jólasveinar were trolls or elves or something in the middle. Friends at home want to know all about the strategies Icelanders employ to avert elf-related disaster. So let’s talk about it.

What’s the difference between álfar (elves) and huldufólk (hidden people)? Tell me a story.

Short answer: none. Scholars of Icelandic folklore generally agree that the two terms refer to the same entity. Elves are, by their nature, able to become invisible to humans. They are also very often beautiful, well-dressed, affluent, but they can either be helpful to humans or vengeful toward them. Elf stories are oftenmoral stores – but with quite a lot of interspecies action. Worth noting – and perhaps looking into – is the double standard in the elven tales: men who go to bed with elves are rewarded for getting in premarital practice, but women who do so are often punished for their transgression. Let’s not forget that. But sometimes there are quite lovely tales of forbidden elf-human pairs dying in each others arms, the survival of their half-elf, half-human heir, and the presumed dropped-jaw of the woman’s human-husband who has found them (only after oppressing her for her entire life).

But let’s talk invisibility and moral lessons. Take the story Sýslumannskonan á Bustarfelli – The Magistrate’s Wife of/in Bustarfell (Manor), who one night goes to sleep without lighting the candles in the bedroom (baðstofa, here) and doesn’t wake as usual to wake the servants, etc. Instead, she’s fast asleep, and her husband instructs the servants to keep it that way. When she finally wakes (langt er liðið á nótt), she has the most fantastic story to tell:

An elf man came to her in the night – presumably in her dream – and asked her to follow him. He led her to a rock, which he walked around 3x clockwise. It transformed into a house! A “little but decorative” house (lítlu og skrautlegu hús), but still, a house. There, inside this house that was a stone 3 seconds ago, is his elf-wife, who is in labor on the floor, and “would die without the assistance of a human being” (muni deyja nema hún njóti að fulltingis mennskra manna*). The wife says “May the Lord Jesus help you,” and everything turns out okay and the elf delivers. The elf-mother starts to tidy the house, and eventually asks the woman to clean the baby up, anointing its eyes with ointment. But the woman decides she wants some of the ointment, too, and sneaks some into her eyes when nobody is looking. Before she leaves the house, she’s given a beautiful golden, embroidered cloth as a reward for the good thing she’s done.

*Mennskri maður is terminology often used in these folk tales to solidly differentiate humans from otherworldly beings.

But the catch is – she’s done something wrong. She’s now able to see the elves. The elf-man lead her out of the house, circled around it three times counter-clockwise, and walked her home safely. But now, since she’s slipped some ointment into her eyes on the sly, she can see the otherwise-invisible-don’t-call-us-we’ll-call-you elves. And she learned that the elves were both clever and intuitive when it came to weather: when they spread out hay on the ground to dry, it didn´t rain – when they didn´t – it did.

She decides at one point to go to the shops in town. And when she goes into the store, she sees, with her arms full of goods, the elf-wife. And she goes right up to her, saying enthusiastically, “And so we meet again!” Uh-oh.

The elf woman turns to her angrily, spits in her right eye (where she’d applied the ointment) and disappears from sight. And of course, so did every other elf because now the woman can’t see them any longer. But she does keep the cloth, which you can visit at the National Museum.

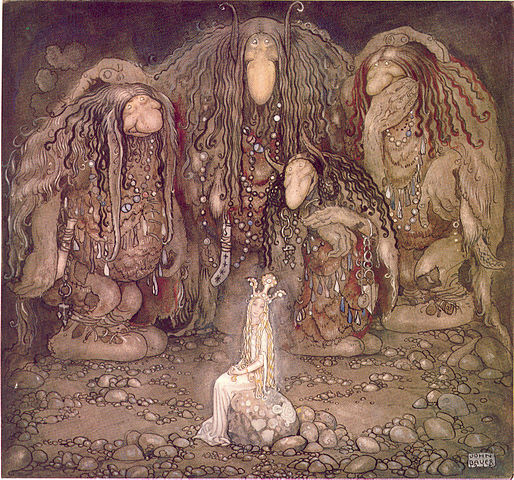

So, then, what’s a troll?

ronger than humans, often ugly, greedy, and cruel. Trolls live in mountains, cliff walls, and gigantic stones. They do eat people, but they also have a taste for fish. They’re pagan beings, but more primitive and more closely connected to nature than humans, and they lack a sort of moral code or ethics to guide their society. They don´t use knives and forks, but they do work with their hands. They´re definitely an older culture than (and perhaps of) human beings, but they do not read books. Sometimes, they turn to stone in sunlight, as in the story of the nátttröll, when a scared girl left alone on Christmas night distracts a tröll with a rhyme until daybreak.

But trolls aren’t always bad. Sometimes they’re quite helpful. For example, in the story Skessan á Arnarvatnsheiði – The Troll Giantess Of Arnarvatnsheidur, a man falls in love with a tröll woman, who has given he and his traveling friend shelter from the cold, and sent them on their way with a heap of trout. But during the night, presumably, one of the travelers made love with the troll – and so, halfway home, he splits, without a trace to return to his lovely troll mistress. The legend states explicitly that we’re not sure if they have kids or not, but there are a lot of half-troll, half-humans running around because, according to legend (this legend), there are only two male trolls left, but there are 50 women.

TW: some of the sexual encounters between trolls and humans in the folk tales are, in fact, what we would probably call sexual assault.

At other times, like the giantess Grýla – mother of the Yule Lads – trolls eat people. Kids, specifically. After her husband Leppalúði has shoved them in a bag.

Is there a moral to the story?

Sometimes, but generally these troll stories are thought to be outlets for human fears and desires, Freud-esque. Trolls are perhaps a little bit less black-and-white than trolls, and their stories are less easy to digest (no pun intended).

So, based on that limited information, who’d you rather run into? An clever (but possibly mean-spirited) elf? Or an oafish (but potentially kindhearted) troll?

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.