Instead of a Russian Time Machine: «Алмазный мой венец» [My Diamond Crown]! Posted by josefina on Oct 13, 2009 in Culture, History

How many times have we not wished that our neighbor was «сумасшедший учёный» [a crazy scientist] who would one day come knocking on our door, asking if we’d like to try out his newly invented «машина времени» [time machine]? The scene, as I always had pictured me it (and I’m sure you see it in pretty much the same way), would remind a lot of the classic Soviet movie «Иван Васильевич меняет профессию» [“Ivan Vasil’evich: Back to the Future”] except given the chance I wouldn’t want to switch ‘profession’ with any Russian tsar and end up in the 16th century. If I had the chance to travel anywhere I wanted to in Russia’s exhilarating past I’d choose to go visit the 1920’s. If I had a lunatic of a Russian neighbor «с такими очками, как у студента физического факультета в советские времена» [with the kind of glasses of a student of the Physics Department in Soviet Times] and he would offer me a ride «в его машине времени» [in his time machine], then I would ask him kindly to set the date to somewhere between 1920 and 1926. Why? Isn’t the answer obvious? Because of all the wonderful Russian writers and poets who were alive back then! Who were so young and ambitious and starting out by writing their best work in those first delicate years of the Soviet Union! Because of everything that was happening in Russian culture during the first half of that decade! It was the first fragile years after «Октябрьская революция» [the October Revolution] and a brand new state was building «новый мир» [a new world] that needed not only «новое искусство» [new art] in general but also «новая литература» [a new literature] especially, and this of course included «новая поэзия» [a new poetry].

None of my neighbors here «в студенческом общежитии» [in the student dormitory] are a crazy scientist and none of them (as far as I am aware at this moment in time) are working on a time machine. But the thing is that we don’t really need a time machine in order to travel back to the 1920’s in Russia – all we need in order to feel just as if we were really there is to pick up a copy of «Алмазный мой венец» [“My Diamond Crown”] by Валентин Катаев [Valentin Kataev]. It isn’t a novel. It isn’t a novella. Not a poem. It’s not recollections. And certainly no memoir, not even a lyrical journal… Then what it is? Let’s call it simply «произведение искусства» [a work of art]. A work of art in which Valentin Kataev writes down stories as they appear in his memory: stories mainly about his youth in the 1920’s and his closest friends with whom he used to spend time, read poetry and drink vodka «в Одессе» [in Odessa], «в Харькове» [in Kharkov] or «в Москве» [in Moscow]. Now Kataev’s ‘drunken chronicles’ would mean little to nothing to us – in the year 2009 – had his closest friends not been the most famous Russian writers and poets of the time…

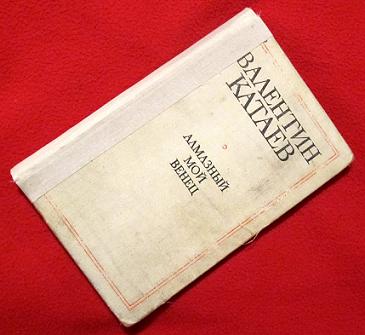

This is how a copy of the very first edition of «Алмазный мой венец» Валентина Катаева» [Valentin Kataev’s “My Diamond Crown”] from 1979 looks like. It was only printed in some 30 000 copies, but had to be reprinted over and over again when it became «культовая книга» [cultic book] in the early 1980s.

While reading Kataev’s work of art – which consists of no more than 221 little pages without any chapters, it’s just one big «сплошной текст» [continuous text] – I kept shivering. Why did this book make me shiver? Reason one: «у меня очень трепетное отношение к русской литературе» [I have a very quivering relation to Russian literature]. Reason two: «у меня склонность к трепету перед русским поэтам и писателям» [I have a tendency to quiver in front of Russian poets and writers]. And Kataev’s work of art is just as much about literature in general as it is about poets and writers. Kataev knew everybody! People who have become in my eyes almost like literary gods after all of the great novels, splendid short stories and poetry I’ve read by them – «Юрий Олеша» [Yuri Olesha], «Сергей Есенин» [Sergey Yesenin], «Владимир Маяковский» [Vladimir Mayakovsky], «Михаил Булгаков» [Mikhail Bulgakov], «Борис Пастернак» [Boris Pasternak], «Осип Мандельштам» [Osip Mandel’shtam], «Велимир Хлебников» [Velimir Khlebnikov], «Михаил Зощенко» [Mikhail Zoshchenko] – are people that Kataev lived with. To him all of these great poets and writers of the 1920s were not simply «товарищи» [comrades] but «друзья» [friends]. Together they did all sorts of things; they lived their lives side by side back then. When Kataev writes about everything these writers and poets did together – about what was strange about life back then, about all of the evenings that happened to get a tad too ‘wet’, about how they were broke as well as when they were rich just after getting something published – it feels as if they’re alive again. While reading Kataev you feel as if these classic Russian writers are coming to life right in front of your eyes. And you don’t need any time machine at all. After a couple of pages you’re already there. Right inside the stormy literary world of a very young, very hopeful USSR – just as young and hopeful as the writers and their creations were back then. And that’s why I shivered all the way through this work of art – I felt like I was actually there!

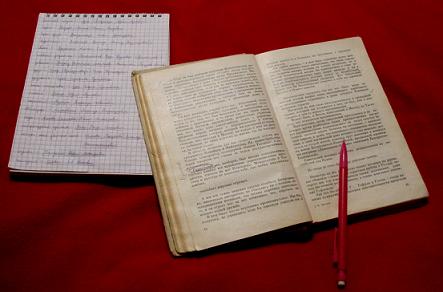

But Kataev doesn’t write his friends’ real names in his text. No, he calls his famous friends something else and thus allows for the reader to figure it out on their own. This is called in Russian for «роман с ключом» [‘roman à clef’ or ‘novel with a key’] and is done so well by Kataev in «Алмазный мой венец» that the copy I borrowed in the library last week – from 1979 – was full of different people’s notes and guesses and question marks and exclamation marks… It was interesting in itself to read what the people reading it before me had come up with…! Some guesses were right, others were wrong – but all of them equally qualified, of course. At times Kataev will give you pretty big hints, though, that you won’t be able to misunderstand. For example when he talks of how he came up for the basic plot behind «Двенадцать стульев» [“The Twelve Chairs”] and gave it as an assignment to be written by «брат» [brother] and «друг» [friend]. It is more than obvious here that the ‘brother’ must be his own younger brother «Евгений Петров» [Yevgeny Petrov] and the ‘friend’ then none other than «Илья Ильф» [Il’ya Il’f].

How should one read «роман с ключом» [‘a novel with a key’] properly, you might wonder? You could try following my example as portrayed above – with a pencil in hand! I made a list of the nicknames in my notebook and while going through the text I filled in the real names next to them as I kept guessing. It was a lot of fun! But then again I am «филолог» [a philologist] and we tend to think things like this are amusing.

Out of the very many interesting things and people you can read about in this truly wonderful work of art, let me mention just a few. I hope that I in this way will give all of you a clearer picture of what this little book it is really about. I hope to show you exactly how close Kataev was with the most brilliant people of his time, of his youth. Not that he himself wasn’t brilliant; after all, he wrote this, didn’t he? And maybe I hope that you’ll read it, too, and come to shiver and smile and be unable to stop reading for curiosity just like I did…

Kataev writes about how he was in love with «синеглазка» [blue-eyed (girl)] when he was very young. She was the younger sister of a writer he calls «синеглазый» [blue-eyed (masculine adjective)]. With this blue-eyed writer he would play in casinos in order to win money and buy vodka and sausage. And he, ladies and gentlemen, is Mikhail Bulgakov!

Kataev would often drink with «королевич» [from the word for ‘king’] and he was among the first to hear this poet’s brilliant «Чёрный человек» [“The Black Person”] – one of the last poems he wrote before taking his life. This is, dear comrades, none other than Sergey Yesenin!

Once «королевич» [Sergey Yesenin] got very drunk and ordered Kataev to take him to the apartment of «Командор» [Commander], since he was convinced that they deep down weren’t poetical enemies at all, but brothers who loved each other deeply. Who is then «Командор»? You guessed it: the only one to be written with a big letter in Kataev’s work of art is of course Vladimir Mayakovsky!

But more than anyone else Kataev writes about «ключик» [‘the little key’]. This writer and poet also grew up in Odessa, just like Kataev did, and they became best friends already when they were still both teenagers. «Ключик» then went and became a literary legend after publishing the novel «Зависть» [“Envy”] – about which I have written a post here on the blog last spring – and Kataev ended up traveling Europe after his best friend’s death reading lectures about him. Yes. Yes. I knew you would understand it straight away – this is clearly «Юрий Олеша» [Yuri Olesha]!

And then there’s «мулат» [‘mulatto’ – Boris Pasternak] and «щелкунчик» [‘nutcracker’ – Osip Mandel’shtam] and many, many more people and stories left to explore in his book… Too many for a simple blog post about Russian culture. What I hope to have given you today is an idea of what Kataev’s ‘work of art’ is like. I highly recommend that you read it. In the original Russian or in a translation. In the mean time I’ll continue exploring late 20th century Russian literature… and be back with even more revelations like this one! Happy reading everyone!

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

Charly:

Great post! 🙂 Now You’ve really made me want to read Алмазный мой венец! Only I have no time right now… but I’ll look it up in our library this semester for sure!