Confused About Russian Pronouns? Posted by yelena on Sep 13, 2011 in language, Russian for beginners

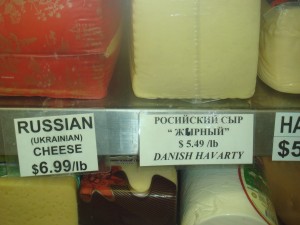

Is Russian grammar confusing? You bet! Just check out this photo I snapped at a Russian store in New Jersey.

Is Russian grammar confusing? You bet! Just check out this photo I snapped at a Russian store in New Jersey.

Do you ever get frustrated with Russian grammar rules? Are you tired of declension tables, unpredictable word stress and having to memorize endless exceptions from the rules?

Well, I am not about to offer a magic bullet for your troubles (although this is a post about grammar). However, I do have a great phrase to teach you. When things are confusing and difficult to understand, Russians say «без пол-литра не разберёшься» [lit. can’t figure it out without a half-liter (of vodka)] as in

«Грамматика – дело сложное. Тут без пол-литра не разберёшся» [Grammar is a complicated thing. It’s hard to figure it out.]

Even though I am a native speaker of Russian who paid reasonably good attention in school, I find many grammar rules confusing to say the least. Plus «школа была давно» [school was a long time ago]. Somehow remembering that «жи/ши пиши с буквой и» [write «жи» and «ши» with a letter «и» (even though you tend to hear «ы»)] just isn’t enough to pass for «образованный человек» [an educated person].

For example, I’ve been stumbling over when to use «него», «неё», «них» and when to use «его», «её», «их».

But let’s back up for a minute to review a few Russian «личные местоимения» [personal pronouns], particularly «он» [he], «она» [she], «оно» [it], and «они» [they].

In Russian, pronouns have attributes of

«лицо» [person] – the ones above are all «местоимения третьего лица» [third person pronouns]

«род» [gender] – «мужской» [masculine], «женский» [feminine] and «средний» [neuter]

«число» [number] – «единственное» [singular] and «множественное» [plural]

«падеж» [case] – yes, the pronouns will have different case endings, just like Russian nouns

Here’s a declension table for third person pronouns:

|

Case |

Singular |

Plural |

||

|

|

Masculine |

Feminine |

Neuter |

|

| Nominative | он | она | оно | они |

| Genitive | его | её | его | их |

| Genitive (w. prep) | него | неё | него | них |

| Dative | ему | ей | ему | им |

| Dative (w. prep) | нему | ней | нему | ним |

| Accusative | его | её | его | их |

| Accusative (w. prep) | него | неё | него | них |

| Instrumental | им | ей, ею | им | ими |

| Instrumental (w. prep) | ним | ней, нею | ним | ними |

| Prepositional | нём | ней | нём | них |

As you can see, this table is just a little bit longer than usual thanks to Genitive (w. prep), Dative (w. prep), Accusative (w. prep) and Instrumental (w. prep) cases.

The “w. prep” means “with preposition”. So now it all seems clear enough – if you use these pronouns with prepositions, you will use a longer form, the one that adds «н» at the beginning of each pronoun. Simple, isn’t it? Why would I ever get confused in the first place?

Ok, as you probably guess, this rule is somewhat incomplete in its explanation of when to append «н» to third person pronouns and when leave them as is…

So here it goes:

While use of «н» at the beginning of these forms of third person pronouns is mandatory with most prepositions, it is downright incorrect with some. But here’s the best part – there are quite a few prepositions with which it can go either way.

Oh, boy… Looks like we need another table, but since Russian language is rich in prepositions and your patience and time are limited, I’m going to skip it (here it is on Gramota.ru)

Here’s what I suggest instead – memorize the following twelve prepositions:

- благодаря [due to]

- включая [including]

- вне [outside]

- вопреки [against]

- вслед [following]

- навстречу [toward]

- наперекор [against]

- наподобие [like]

- подобно [like]

- посредине [in the middle of]

- посредством [by way of]

- согласно [in accordance with]

When you encounter these, you should not use «н» with the third person pronouns. Compare (I capitalized the preposition + pronoun combinations for added emphasis):

«В наше время высшее образование необходимо. Только БЛАГОДАРЯ ЕМУ вы сможете найти высокооплачиваемую работу» [These days higher education is a necessity. Only with it will you be able to find a high-paying job.]

«В наше время предприимчивым людям нет необходимости в университетском дипломе. Они могут стать миллионерами ВОПРЕКИ отсутствию ЕГО.» [These days entrepreneurial individuals have no need in university diplomas. They can become millionaires in spite of not having such.]

Now, if you just use «н» in all other cases, you’ll be set.

«Кредитные карточки необходимы. БЕЗ НИХ становится трудно не только покупать дорогие вещи, но и путешествовать» [Credit cards are a necessity. Without them it’s becoming difficult to buy expensive things as well as to travel.]

«Способов избежания долгов много. В ЧИСЛЕ НИХ – перестать пользоваться кредитными карточками» [There are many ways to avoid debt, including avoiding use of credit cards.]

So, memorize the twelve prepositions and you’ll be speaking «грамотно» [properly]. In fact, not only will you be speaking just as properly as native speakers of Russian, but, in some cases, «даже лучше них» [even better than them].

Which brings me to the last part of this «н» rule:

Whether you use «н» or not in third person pronouns following comparative adjectives is totally up to you (thus saying «даже лучше их» is just as grammatically correct).

Warning – there’s going to be more grammar posts this week. But if there’s any particular grammar topic you’re interested in, let me know.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

Ryan:

For me at least, these rules always make more sense when I know why they’re there. The н shows up because prepositions like к, с, and в used to be кън, сън, and вън, where ъ was a supershort vowel kind of like the ‘oo’ in English ‘books’. Slavic speakers way back before the 10th century decided that they didn’t want to end their syllables with consonants, and so the н got lost almost everywhere but the pronouns, where it moved from the end of the preposition to the beginning of the pronoun. Later on, of course, people stopped saying the ъ. The preposition у never had н, though. Neither did за, из, or the lower-frequency two-letter prepositions. People just started using н-affixed pronouns with every preposition.

So of course the twelve prepositions in the list shouldn’t have н on the pronouns that they precede. It was never there in the first place, and I guess Russians don’t think of them as quite as prepositional as the ones that take н.

yelena:

@Ryan Ryan, great comment. There are a couple of posts coming up at the end of the week that you will probably enjoy. They are guest posts by someone who has very similar approach to yours and who is also passionate about learning Russian. So stay tuned!

Emily:

Thank you for your informative and interesting posts! I don’t get many chances to study Russian any more, so your posts give me an excuse to brush up on my grammar! Thanks!!

yelena:

@Emily Hi Emily, thank you for reading. I’m glad you found this post useful 🙂

Greg Lapin:

participles, not the Russian ones such as чита́емый. But the ones in spoken language which are impersonal constructions, are confusing to me. example

I read a book is straight-forward. but commonly in Russian, it is written 2 different ways (a book is being read): книга читается or читают книгу. and it can be done in the past tense as well. book stays nominative i guess in one. sorting through this in part of a post would be helpful, especially if its accurate that its usage is pervasive. thanks

yelena:

@Greg Lapin Greg, this is an interesting topic and something that comes up often especially in works of literature. I’m going to think of a good post for this subject. Thank you for the idea!

Richard:

A post on word order in Russian would be helpful for me. English is fairly rigid when it comes to word order but Russian, as an inflected language, allows for greater flexibility in word order. Learning vocabulary is one thing, but learning how to construct a sentence to achieve a desired effect is something else.

yelena:

@Richard Richard, this is awesome – I was just discussing this very subject (word order) in an e-mail with a friend. Also, I answered the question you asked about word stress in short form adjectives (although I’m not sure it’s very helpful).

Alan:

Ryan, thank you for the explanation. I certainly find things easier to understand and remember with such rationalisations provided. And as a plus it helps makes grammar feel a little less abstract and a little more reasoned!

jacki:

Some time ago there was an explanation of

понедельник but now I can’t find it and my students are wondering ehre it came from. HELP!!!! rooskiproff@gmail.com

yelena:

@jacki Jacki, you might be looking for this old post. Does it help?

Sasha:

There’s a mistake on that cheese picture. It’s российский(with two “С”), not “росийский”.

yelena:

@Sasha Sasha, you should see some other signs in that particular store. Перлы грамматики и стиля!