Russian grammar is fun Posted by bota on Feb 16, 2021 in Grammar, language

There is a fun Russian grammar post circulating online that’s said to have been compiled by the Associate Dean of Foreign Languages Faculty at Moscow State University, Alla Leonidovna Nazarenko. Most Russian speakers find the post funny, whimsical even, or at least curious. Today, we go over my favorites from her list. Brace yourselves for the best the Russian language has to offer: sarcastic jabs disguised as compliments, trickster verbs, and double-negatives. To spice things up, I’ll see if google translate will pick up on any of the fine linguistic intricacies of Russian for some of these sentences.

Word Order Matters

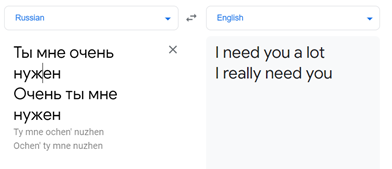

Take the phrases “ты мне о́чень ну́жен” and “о́чень ты мне ну́жен”. Though they literally translate to “I really need you”, just with slightly different word order, they are opposites. The first one is a sincere “I really need you” worthy of a tear-jerking movie scene where characters confess their profound love for one another. The second is likely to be said with an extremely sarcastic eye-roll or even a “pfff” type of remark and equal to “pfff, I don’t need you”. Alas, Google didn’t stand a chance.

Negatives

“Ча́йник до́лго остыва́ет” and “ча́йник до́лго не остыва́ет” both mean “the tea kettle has been cooling down for a while now”.

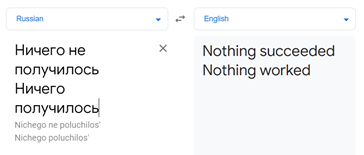

If someone says “Ничего́ не получи́лось!” they are expressing sadness and frustration over a failed task. Meanwhile, if someone says “Ничего́ получи́лось!” they are approving whatever was accomplished with a hint of genuine surprise that it worked. Machine Translation – 0, Russian – 2.

Lost in Translation

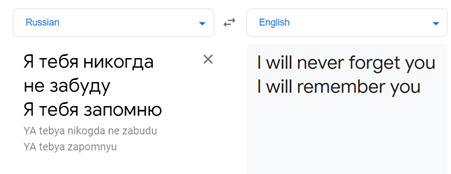

The phrase “Я тебя́ никогда́ не забу́ду” (I’ll never forget you) sounds romantic while “Я тебя́ запо́мню” (I’ll remember you) has a much more threatening effect.

The trick is in the word “запо́мнить”. It’s tempting to only equate it with the nostalgic meaning of “remember” because “по́мнить” is mostly used in sentences like:

Я по́мню запах ба́бушкиных духов Кра́сная Москва.

I remember the smell of my grandma’s perfume “Red Moscow”.

“Запо́мнить” in “Я тебя́ запо́мню” makes the sentiment much closer to “I’ll commit you to memory” (though nobody says that in English) or the simple “I’ll remember you”, but in a much more threatening way. By the way, is it just me, or the phrase “I’ll commit you to memory” really does sound threatening and worthy of the next Liam Neeson monologue?

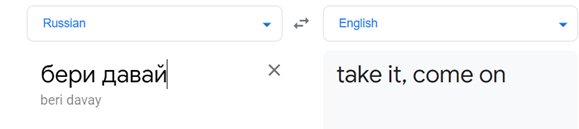

“Бери́, дава́й” (Take it, come on!) is quite a hoot and half because at first glance the verbs have opposing meanings: “бери́” is “take” and “дава́й” is “give”. However, the word “дава́й” here means “come on”. Google – you’re back in the game! (Google – 1; Russian – 2)

One would think the words “бесчелове́чно” and “безлю́дно” will be synonymous, since “человек” (person) is the singular of “люди” (people). Wrong. “Бесчелове́чно” means “inhumanely” while “безлю́дно” is “deserted”.

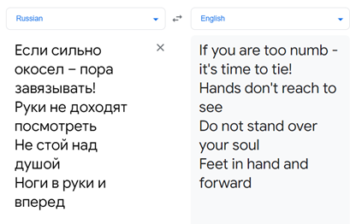

Speed round! How will Google translate these phrases?

“Е́сли си́льно окосе́л – пора завя́зывать!”

“Ру́ки не дохо́дят посмотре́ть”

“Не сто́й на душо́й”

“Но́ги в ру́ки и вперёд”

The first one is about knowing when to stop drinking. “Окосе́ть” means to get cross-eyed and to get wasted, so we get a nice play on words in the phrase above. “Завя́зывать” is literally to “tie” like “завя́зывать шнурки́” (“to tie shoes”). Idiomatically though, it means to “stop doing something” or “to stop drinking” in this context.

“Ру́ки не дохо́дят посмотре́ть” is a linguistic equivalent of a Frankenstein’s monster stitched up from random parts. What can arms (“ру́ки ”) have to do with the negative of the verb for getting somewhere (“не дохо́дят ”) in order to look at something (“посмотре́ть”)? Do you know? Because I haven’t gotten around to look that up (or should I say my hands didn’t get to look that up). Wink-wink.

You can use “не сто́й на душо́й” to let the person annoying you know that they are annoying you. Physical proximity is not paramount, even though the phrase literally means “don’t stand above my soul”.

And even though Google didn’t stand a chance with the “но́ги в ру́ки и вперёд”, its literal translation carries over the sentiment of “you should get started on that thing right away”.

Adjectival rivals

- “О́чень у́мный” is likely a compliment but can be a sarcastic remark depending on the speaker’s intonation.

- “У́мный о́чень” is definitely a sarcasm.

- “Сли́шком у́мный” is more of a threat and comes off as a suggestion for someone to stop talking.

For more, check out a similar blog I’ve done on Russian phrases-homophones.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.