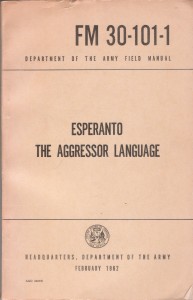

The US Army used Esperanto? Posted by Chuck Smith on Feb 8, 2013 in Uncategorized

Did you know the US Army once used Esperanto? In training the military, they wanted to more realistically simulate the language situation during combat. So, the “aggressor forces” learned Esperanto. Apparently it was chosen, because of how easy it is to learn. I’m sure Zamenhof (the initiator of Esperanto) would’ve been surprised to hear about the US Army using his “language of peace” (Zamenhof initially made Esperanto, so that everyone could speak to each other and thus be easier to have peaceful relations with everyone. To be fair, during the first Universal Congress of Esperanto in Bologna-sur-Mer, France in 1905, it was unanimously accepted to define an Esperantisto as follows:

Esperantisto estas nomata ĉiu persono, kiu uzas la lingvon Esperanto tute egale, por kiaj celoj li ĝin uzas. Esperantisto sekve estas ne sole tiu persono, kiu revas unuigi per Esperanto la homaron, esperantisto estas ankaǔ tiu persono, kiu uzas Esperanton ekskluzive por celoj praktikaj, esperantisto ankaǔ estas persono, kiu uzas Esperanton por gajni per ĝi monon; esperantisto estas persono, kiu uzas Esperanton nur por amuziĝadi; esperantisto fine estas eĉ tiu persono, kiu uzas Esperanton por celoj plej malnoblaj kaj hommalamaj.

English translation:

An Esperantist is every person who uses the Esperanto language completely irregardless of their reason. An Esperantist is not only someone who dreams of uniting humanity under Esperanto, but also someone who uses Esperanto exclusively for practical purposes, and also someone who uses it to earn money, as well as someone who uses it for their amusement. An Esperantist is even someone who uses Esperanto for the most evil and lowly ways.

Back to the manual itself, I was surprised to read the following in the beginning of the manual:

Esperanto is not an artificial or dead language. It is a living and current media of international oral and written communication. Its basic rules of grammar are such that it will remain a live language because it can assimiate new words that are constantly being developed in existing world languages.

After I received my used copy on Amazon last year, I was most amused by the fact that here in my hands, I’m holding a manual on how to learn Esperanto completely focusing on military vocabulary and dialog. Here’s an epic paragraph from the example dialog:

On this chart is shown the organization of Aggressor military forces including the following echelons: squad, section, platoon, company, battery, battalion, regiment, brigade, division, army, army group, and regional command. In addition, the basic types of Aggressor weapons are listed: pistol, rifle, machine gun, mortar, recoilless rifle, howitzer, rocket, rocket launcher, missile, tank, and armored carrier.

And its translation into Esperanto:

Sur la karto estas montrata la organizaĵon de la Agresaj militfortoj enhavanta la sekvantaj niveloj: areto, sekcio, plotono, roto, baterio, bataliono, regimento, brigado, divizio, armeo, armegrupo, kaj regiona komando. Apud, la bazaj tipoj de Agresaj armiloj estas listiginta: pistolo, riflo, maŝinpafilo, bombkanono, senresalta pafilo, kanono, haŭbizo, raketo, ĵetaĵo, tanko, kaj kirasa portilo.

Somehow I’m very much going to doubt that any of those new words you just learned will be of much use to you, but the manual is pretty incredible. I was most disappointed to discover that 205 of the 233 pages of Esperanto: The Aggressor Language were just an English-Esperanto dictionary (bi-directional), albeit entertaining in how military-centric the vocabulary is, such as alpha rays, iron girder, and canonical scanning!

In looking into this further, I discovered that you can read the entire book online for free. Also, I know that when Sam Green was producing his Esperanto documentary The Universal Language, he ran across a four-minute video that the US army made to summarize its field exercise. Surreal. Watch it below!

*Book cover image under CC license: BY-SA Cindy McKee.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

About the Author: Chuck Smith

I was born in the US, but Esperanto has led me all over the world. I started teaching myself Esperanto on a whim in 2001, not knowing how it would change my life. The timing couldn’t have been better; around that same time I discovered Wikipedia in it’s very early stages and launched the Esperanto version. When I decided to backpack through Europe, I found Esperanto speakers to host me. These connections led me to the Esperanto Youth Organization in Rotterdam, where I worked for a year, using Esperanto as my primary language. Though in recent years I’ve moved on to other endeavors like iOS development, I remain deeply engrained in the Esperanto community, and love keeping you informed of the latest news. The best thing that came from learning Esperanto has been the opportunity to connect with fellow speakers around the globe, so feel free to join in the conversation with a comment! I am now the founder and CTO of the social app Amikumu.

Comments:

Neil Blonstein:

So far I’m the only Esperantist to actually have bumped into a friend of a friend who learned basic Esperanto during USA military service. You can find the interview at my blog http://esperantofriends.blogspot.ch/2010/03/39-agressor-language-esperanto-1953.html. My conclusion=next to nobody got involved in the Esperanto movement as a consequence of a military course using Esperanto.

Kieran Maynard:

Bizarre! Thanks for sharing. The interrogation is hilarious. I love how the POW points to the book for the interrogator. Such good sportsmanship!

James:

From what I saw in the video, the manual didn’t come with a pronunciation guide!

H.K. Fauskanger:

It seems plain that the soldiers in the video never had a proper introduction to Esperanto pronunciation. The plural ending -j is pronounced like in English (as in “John”). The proper pronunciation would be like English “y”.