Arabic Parsing vs. Diacritics Posted by Ibnulyemen اِبْنُ اليَمَن on Nov 16, 2017 in Arabic Language, Grammar, Pronunciation

In acquiring Arabic, it is exceedingly essential that articulation rules, namely diacritics الحَرَكَات, be known from the outset. Knowing how to pronounce sounds and words intelligibly leads to better learning and communication. The ability to pronounce words effortlessly speeds up vocabulary acquisition and retention. Likewise, proper pronunciation leads to more comprehensible speech. This post is about role of diacritics الحَرَكَات and parsing الإِعْرَاب in Arabic.

In most world languages, vowels play a key role in pronunciation. That is, it is vowels that cause irregularity in pronunciation. Take English as a typical example. The difference in pronunciation between ‘them’ and ‘theme’, ‘hug’ and ‘huge’, ‘not’ and ‘note’, ‘hid’ and ‘hide’ and so forth is triggered by a vowel. In Arabic, the source of difference in meaning between عَلِمَ, عَلَمٌ, عِلْمٌ, and عَلَّمَ is the vowels. Similarly, it is vowels that makes Arabic word-order more flexible, hence you can have three or more variants of the same sentence. Vowels in Arabic are basically the diacritical marks.

Diacritics الحَرَكَات:

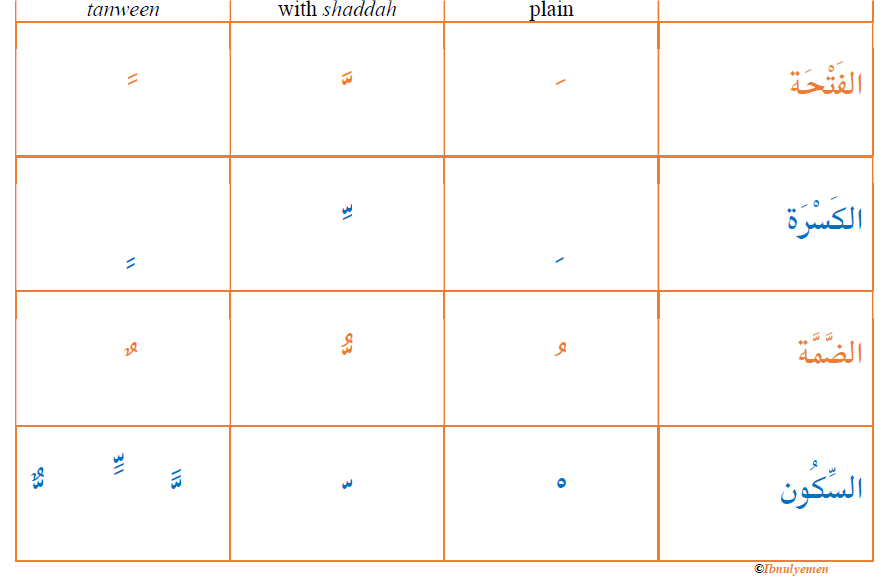

Diacritics in Arabic are marks that accompany consonants. They are sometimes called short vowels. The vowel system in Arabic is a simple one as it includes only three vowels. These are the fatHah َ , kasrah ِ , and DHammah ُ . Besides these, there are two others: sukuun ْ and shaddah ّ. tanween is a variant for each of the first three, and it has a grammatical value for it indicates indefiniteness of nouns and adjective. Shaddah has seven variants: plain, with fatHah, with kasrah, with DHammah, and with tanween. Hence, there are fourteen Arabic diacritical marks, as summarized in the table image above.

Since it has seven variants, let me dismantle the complexity of shaddah. In English, a sequence of two consonants is called a geminate, as in ‘innate’. It is basically the same in Arabic. Shaddah is s a sequence of two Arabic consonants. The first consonant must be accompanied with a sukuun, then second is companied by a fatHah, a kasrah, a DHammah, or their tanween variants. What about the ‘plain’ shaddah? It is sequenced of two consonants each is accompanied by a sukuun. Here are examples:

- كَ تْ تَ بَ becomes كَتَّبَ ‘to cause someone to write’

- ال حُ بْ بُ becomes الـحُبُّ ‘the love’

- عُ لْ لِ مَ becomes عُلِّمَ ‘was educated’

- حُ رْ رْ becomes حُرّ ‘be free’

- حُ رْ رًا becomes حُرًّا ‘be a free …’

- حُ رْ رٌ becomes حُرٌّ ‘be a free …’

- حُ رْ رٍ becomes حُرٍّ ‘be a free …’

The Role of Diacritics:

Besides pronunciation, another primary role of Arabic diacritical marks is meaning-related. That is, they disambiguate words as they distinguish nouns from verbs, active verbs from passive verbs, and transitive verbs from intransitive ones, as in the table below:

| verb (active) | verb (passive) | causative verb | noun | |

| شرب |

شَرِبَ ‘he drank …’ |

شُرِبَ ‘… was drunk.’ |

شَرَّبَ ‘… make sb drink …’ |

شُرْبٌ ‘drinking’ |

| علم |

عَلِمَ ‘he knew …’ |

عُلِمَ ‘… was known’ |

عَلَّمَ ‘… made sb know …’ |

عِلْمٌ ‘knowledge’ |

| لبس |

لَبِسَ ‘he wore …’ |

لُبِسَ ‘… was worn’ |

لَبَّسَ ‘… made sb wear …’ |

لِبْسٌ ‘dress’ |

Parsing الإِعْرَاب:

You might have come across إِعْرَاب ‘parsing’ in the course of your Arabic learning to date. Parsing is the assignment of diacritical marks to word endings. This grammatical feature is notoriously difficult among native speakers of Arabic since its natural usage has been lost from everyday communicative use of Arabic. That is, as the child picks up Arabic, he/she never hears this feature in the daily linguistic input of the people around him/her.

Essentially, diacritical marks at word endings are called cases. There are four cases in Arabic: مَرْفُوع ‘nominative’, منَصُوب ‘accusative’, مَجْرُور ‘genitive’, and مَجْزُوم ‘jussive’. Here I briefly elaborate on the first three with respect to nouns and adjectives only. Take the word الكِتَاب ‘the book’, it has three variants according to its position in the sentence: الكِتَابُ, الكِتَابَ, الكِتَابِ. So, how does this matter?

The Role of Parsing:

Parsing in Arabic impacts the language in two ways. First, it makes the language more spontaneous. That is, when you add cases to word endings, speech becomes more natural and connected with very few pauses between words. For example, in the table below, the sentences that have both diacritics and parsing added are pronounced a lot faster, more naturally, and with fewer pauses between words, compared to the two sets.

| no diacritics | with diacritics | with diacritics and parsing |

|

كتب الولد الدرس. |

يَكْتُب الوَلَد الدَّرْس. |

يَكْتُبُ الوَلَدُ الدَّرْسَ. يَكْتُبُ الدَّرْسَ الوَلَدُ. الوَلَدُ الدَّرْسَ يَكْتُبُ. الدَّرْسَ يَكْتُبُ الوَلَدُ. |

|

لبست الثوب الجديد، وحضرت حفل المدرسة. |

لَبِسْت الثَّوْب الجَدِيْد، وحَضَرْت حَفْل المَدْرَسَة. |

لِبْسْتُ التَّوْبَ الجَدِيْدَ، وَحَضَرْتُ حَفْلَ المَدْرَسَةِ. |

In addition, parsing makes Arabic less bound by word-order rules. As you can see under the third column, the first sentence can have four variants provided that diacritical marks of parsing are added.

Is parsing difficult? No, not really. Once you become acquainted with sentence analysis, you should be able to parse any sentence. I will dedicate a post for this at some point.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.