Tanween [Nunation] in Arabic: Types, Meanings, and Assignment Posted by Ibnulyemen اِبْنُ اليَمَن on Mar 23, 2017 in Arabic Language, Grammar, Pronunciation

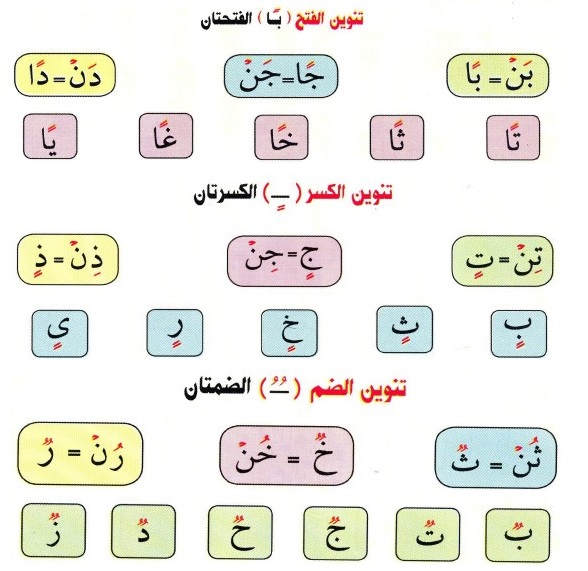

In an earlier post, we learned that basic Arabic diacritical marks have linguistic values. So does the Arabic nunation, i.e. tanween تَنْوِيْن. Besides its distinct pronunciation, it has both grammar- and meaning-related values. There are three types of tanween:

- fatH ( ً ), denoted by double fatHah

- kasr ( ٍ ), denoted by double kasrah

- dhamm ( ٌ ), denoted by double Dhammah

Tanween is added to the end of Arabic nouns, adjectives, (and adverbs, fatH only). For a pure beginner learning Arabic, the most common words with tanween that he/she hears at the outset of his learning are these:

مَرْحَبًا hi

أَهْلاً hello

أَهْلاً وسَهْلاً hello and welcome

عَفْوًا sorry, excuse me, you’re welcome

All these greeting words, end with a tanween al-fatH. This is not arbitrary; rather, it is governed by the grammar. When a noun is in an object position (among other positions), it is assigned tanween al-fatH. If a noun occurs in a subject position (again, among others), it is assigned tanween al-dhamm. The noun is assigned tanween al-kasr if it occurs after a preposition, as in these examples:

لَبِسْتُ قُبَّعَة ً جَدِيدَةً. I donned a new hat.

سَكَنْتُ فِي غُرْفَةٍ كَبِيْرَةٍ. I stayed in a big room.

هَذِهِ قُبَّعَةٌ جَدِيْدَةٍ. This is a new hat.

In many world languages, nouns and adjectives are marked for definiteness. That is, they are either definite, i.e. specific, or indefinite, i.e. don’t refer to a specific thing. ‘a’ and ‘an’, ‘un’ and ‘une’, ‘ein’ and ‘eine’ are the indefinite articles in English, French, and German, respectively. Likewise, tanween is the indefinite marker of nouns and adjectives in Arabic. It is different from other languages in that is it marked diacritically, i.e. using tanween. Plus, it varies according to its position in the sentence. A feature of the tanween al-fatH that you should pay attention to is that it induces a typographic change with words, except with words ending in ta-marbuTah ــة and words ending in hamzah that is preceded by alif, as in these examples:

كِتَابْ (book) كِتَابًا (a book) قَلَمْ (pen) قَلَمًا (a pen) بَيْتْ (house) بَيْتًا (a house)

مَاء (water) مَاءً ( [a] water) هَوَاءْ (air) هَوَاءً (an air) جُزْءْ (part) جُزْءًا (a part)

For the first set of words above, it is required that you add an alif after the tanween. The value of this primarily typographic, i.e. to make it distinct from other words. For the second set of words, alif may not be added after the tanween in the first two words to avoid redundancy, i.e. having two alifs in a row. In the case of the last word, an alif is to be added.

Now, let’s put the above rules into practice.

a) add all three types of tanween to these words and say them out loud. Answers will be provided and explain in our next post.

سَاعَة (watch) دَفْتَر (notebook) شَارِع (street) مَسْجِد (mosque) هَاتِف (phone) مَدِيْنَة (city)

b) choose the correct form of the word. Pay attention of the position of the word in each sentence.

(أ) شَرِبَ الوَلَدُ ……………. (عَصِيرٌ – عَصِيراً – عَصِيرٍ).

(ب) أَدْرُسُ فِي ……………. (جَامِعَةً – جَامِعَةٌ – جَامِعَةٍ).

(ج) عِنْدِي ……………. (كِتَابٍ جَدِيدٍ – كِتَابٌ جَدِيدٌ – كِتَابًا جَدِيداً ).

(د) هَذَا ……………. ……………. (بَيْتٌ وَاسِعٌ – بَيْتٍ وَاسِعٍ – بَيْتًا وَاسِعاً ).

(هـ) العَرَبِيَّة ……………. (لُغَةً صَعْبَةً – لُغَةٍ صَعْبَةٍ – لُغَةٌ صَعْبَةٌ).

c) complete these sentences with a suitable word from this post using the appropriate form of tanween.

.أ) بَيْتِي فِي …………. صَغِيرٍ.

.ب) أَكْتُبُ بـِ ………… جَدِيدٍ.

.ج) هَذِهِ …………… كَبِيرَةٌ. يَسْكُن فِيهَا 2 مَلْيُون شَخْص.

.د) يَقْرأُ مُحَمَّد ………….. كُلَّ شَهْر.

………………. هـ) أَكَلْتُ مَوْزًا وشَرِبْتُ

Another aspect of the tanween that you should know is that it is employed only in the formal usage of the language. That is, in formal settings, native speakers of the language are expected to use it. colloquially, tanween is rarely used with exception of greeting words, such as ahlan, marhban, … etc. When a word is made definite, the tanween is replaced by the corresponding default diacritical mark. I will explain this in next post.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

Scheich Josef:

مرحبا يا ابن اليمن

There is another exception, namely words ending in hamza with carrier alif. For example, no extra alif is added after the tanween al-fatH of مُبْتَدَأً.

Observe also the case agreement of the attribute جديدة with the noun قبعة in your third example هَذِهِ قُبَّعَةٌ جَدِيْدَةٌ.

مع السلامة

يوسف

https://josef.jimdo.com/

ibn al-Yemen:

@Scheich Josef أهلا يوسف

Thanks for your comment. This is meant to be for beginning learners. Such niceties are dealt with in more advanced topics. As for case, it is a typo – shukran for pointing that out.

I hope you enjoyed reading it.

Salaam!

David:

When saying “twenty books”: عِشْرُونَ كِتَاباً is this an `iDaafah / ta may uz construction ? If so the 1st noun of the construct cannot have a tanween. So should the “n” of عِشْرُونَ be dropped ?

ibn al-Yemen:

@David عشرون كتابًا is tamyyeez not idhafah because the very meaning of the word tamyyeez is to distinguish the ambiguous. in the this phrase, عشرون is ambiguous and adding the word كتابًا to it made it unambiguous; therefore, كتابًا is called tamyyeez as it tells what عشرون is.

as for dropping the ن from the first word that occurs in an idhafah structure, this only applies to masculine sound plural nouns جمع المذكر السالم. The word عشرون is not جمع مذكر سالم; it has a specific grammar term. If you had the عشرة in mind, the plural of it is عشرات not عشرون.

I hope this answered your question.

David:

Ibn, thanks, but a related question:

The number 2 (nominative) = إِثْنَانِ

However, 2 as part of the number 12, the 2 changes so we have = إِثْنَا عَشَرَ Note the “n” has been dropped.

Is the n dropped because 2 is now the 1st part of `iDaafah ? If so, should the rule be that “n” is dropped for “ masculine sound plural AND DUAL nouns” ?

If not then why has the “n” been dropped…..

Ref تَمَيُّز Is this a good transliteration >> ta-may-yuz ?? Regards, David

ibn al-Yemen:

very good question!

– first, mind your hamzah, اثنا not إثنا; this is hamat wasl.

– second, you are giving a very sound and solid argument; for اثنا عشر and اثني عشر and اثنتا عشر and اثنتي عشر could have been dropped owing to being part of an idhafah structure. Personally, I did analyze it the way you did during my school days. However, I have not come across a clarification of this sort in Arabic grammar literature.

– As for the dropping of the ن, it applied to both مثنى and جمع, as in these examples:

1) مثني: مهندسا المشروع مجتهدان.

2) جمع: مهندسو المشروع مجتهدون.

another explanation could be that اثنا عشر and اثنتا عشر are called أعداد مركبة and this how they should be written without reference to idhafah.

تَمْييز [tamyyeez] not تَمَيُّز; the latter has a different meaning, i.e. ‘to be outstanding’

I hope this answered your questions and BTW being inquisitive is a good approach to learning. your declarative knowledge will eventually become automatic and part of your ability to communicate efficiently.

David:

Ibn, thanks for you great replies, your time and encouragement.

Ref تَمْييز [tamyyeez] now I`m wondering where should the vowels be placed, without shaddah, I assume: تَمْيِيز (kasara under y) with a transliteration of: tam-yeez (yee being a long vowel) and only “one” letter “y” in transliteration ?

However, I also found تَمْيِيز meaning “favouritism”

Are these two words (tam-yeez and favouritisum) with the same spelling تَمْيِيز ?

Regards, David

Ibnulyemen:

@David it does not matter how you transliterate it; transliteration always vary, and I am not in favor of using these method while teaching/learning a language. It hinders learning.

what matters is how you say it in Arabic. In our تمييز , there are 2 ي, the first has kasrah and the second has sukoon. there’s no shaddah; if the sequence was reversed, that is, if the first ي had sukoon and the second had fatHah, then the ي becomes mushadadah ‘with shaddah. look at these examples:

زْ + زَ = زَّ as in the word نَزَّلَ

but in

لَ + لْ = لَلْ as in شَلَل, i.e. the ل does get shaddah.

to reiterate, a shaddah in Arabic means a sequence of two letters, the first should be with sukoon and the second with any of the short vowels.

I hope it is clear now and feel free to ask any question, I will answer it to the best of my knowledge. Enjoy learning! read my blog posts for more interesting and novel explanations/info.

William Beeman:

I occasionally see people claiming that the tanwin al fath “creates an adverbial use” I can see this in a number of examples, but I don’t understand if this is a productive function in Arabic. I suppose the most common example would be شكراً but also exclamations such as تباً

Can you provide some explanation for this usage?

Ibnulyemen:

@William Beeman first, calling it an adverbial is inaccurate. What is referred to as an adverbial is basically an adjective for a left-out verbal noun, i.e مفعول مطلق. Here are some examples:

– the situation improved economically “تَحَسَّن الوَضْعُ اِقْتِصَادِيًا”. the underlying structure of the Arabic sentence is تَحَسَّنَ الوَضْعُ تَحَسُّنًا اِقْتِصَادِيًا. so the word اقتصاديًا is basically an adjective for تَحَسُّن which is a verbal noun.

– Trump failed diplomatically “عَجِزَ تَرَمب دُبْلُومَاسِيًا”. Underlyingly, it is عَجَزَ تَرَمْبُ عَجْزًا دُبْلُوْمَاسِيًا, so دِبْلُوْمَاسِيًا is an adjective for the verbal noun عَجْزًا, Which is dropped in the surface structure of the sentence.

as for شكرًا, it is slightly different. When you say شكرًا it means أشْكُرُكَ شُكْرًا “i thank you many thanks” and when you say شكرًا جَزِيْلًا, it means أَشْكُرُكَ شُكْرًا جَزِيْلاً “i thank you very many thanks’. So, what is basically happening in this particular instance is that the “subject + verb + object” are dropped and we suffice with the verbal noun المفعول المطلق. Same goes with تَبًا and alike.

I hope this answers your question.

salaam

William Beeman:

Thank you for this explanation, which is really intriguing. I don’t think have seen this elsewhere and I was delighted by your answer. Can I explore it further?

First, would you say that there are actually no “adverbs” in Arabic? There are certainly things that get translated as adverbs in English, but structurally they don’t seem to be identified as a a part of speech by any unified grammatical structure or marking. Your explanation analyzes such uses as adjectives of missing verbal nouns that duplicate the verb for which the verbal noun is the direct object.

If there is a missing verbal noun, how can we supply that noun. Will any verb + absent verbal noun suffice?

Can you help with the following examples where the words are not clearly (at least to me) adjectives? This would clarify things a lot. You are most kind to take time to answer picky questions like this.

تقريباً

عادةاً

معاً

فعلاً

There is a second aspect to my question, and that is whether this usage is “productive,” meaning can one coin these usages freely as one can do in English, converting adjectives and nouns to adverbial use?

stupid—>stupidly (بغباءاً)

أجاب بغباءاً

Thanks so much!

Ibnulyemen:

@William Beeman Technically, there are not such things as adverbs and adjectives in Arabic. Such grammatical categories are used by teachers of Arabic in Western universities to based on their knowledge of English and to suit the teaching context they are in. What is normally described as adjectives are nouns (of course, there are up to eight different types of nouns in Arabic, some of them can be used attributive or predicatively to qualify another nouns, so they wrongly called adjective. Even words such كبير , طويل, فرح and so forth are not adjective. They are nouns similar to active participles and passive participles.

The verbal noun in any given sentence is derived from the main verb of that sentence, and its use is strictly for emphasis, that is if it is dropped it does not affect the essence of the sentence. Adding it, however, adds more semantics to the sentence, i.e. emphasis, urgency …. For instance.

قَصَنا العدو قصفًا ضاريًا.

if you say: قصفنا العدو without the verbal noun قصفًا , it is meaningful. If you add it, it means that the action of قصف ‘shelling’ was vigorous.

تقريبًا is not an adjective. it is a verbal noun from the verb قرَّبَ, that is قَرَّبَ تَقْريبًا.

عادة is not adjective either. it is a verbal noun from the verb تعوَّد تعودًا / عادةً “to be accustomed to do something frequently”

معًا is an adverb of place that indicates companionship, so we you say جلسنا معًا, it means جَلسنا مع بعضنا بعض.

فعلًا is a verbal noun from the verb فَعَلَ فعلاً. It emphasizes the the verb فَعَلَ indicating that action was done well, so when someone says something and another replies with فعلاً, it means “well-said” or “absolutely right” or حَقًا.

for the last example, بغباء does not get tanween my friend because it is preceded by a preposition, so don’t say بغباءًا. You can use بـ followed by a verbal to function in the same way as an adverb in English; e.g.:

عَمِلْتُ بِهِمَّة. I worked diligently (literally translation is: I worked with diligence).

I hope this answers your interesting questions.

William Beeman:

Can I add three more examples?

قبلاً

بدلاً

ليس سئاً (I understand that ليس takes a predicate in the accusative, but what is the predicate in this case?)

Ibnulyemen:

@William Beeman قبلاً is an adverb

بدلًا is a verbal noun

the predicate in ليس سيئًا is سيئًا. the affirmative nominal sentence is هو سيءٌ; while negating it with لَيسَ the topic/subject هو is embedded and implied inside the verb and the predicate is سيئًا and it get tanween fatH because it the predicate of ليس.

salaam!

William Beeman:

@Ibnulyemen Thank you so much for your erudite and lucid explanation. I am a linguistic anthropologist and understanding Arabic based on its internal logic rather than categories of grammar that were devised to explain other non-Semitic languages is a very important goal. This really falls into the general question of “philosophy of grammar.” I am so impressed by your understanding of this. Have you or others written more on this topic? I haven’t been able to find anything that deals with Arabic grammar at this level, and I would appreciate any reference you might be able to provide.

As a footnote, I should point out that “adjective” and “adverb” is a concept that doesn’t really apply in many other languages. Japanese and Chinese are examples. But Arabic goes even farther, because the distinction between “noun” and “verb” is also blurred. Still, there are some things that do seem to be real nouns–especially borrowings from other languages, botanical terms, animal names and geographical borrowings. So Arabic must deal with things that get assimilated from sources outside of the triliteral or quadrilateral root system.

Forgive me for going on like this. You may not wish to clutter the blog with this discussion. If you are interested, we might continue this off-line.

Reband:

Hello, I just have a question about tanween of fatha, why there is an alif after you put tanween of fatha but not for adding tnween of kasra and dhamma? like سيئًا,عادةاً