Chinese Bamboo Flute (笛子) Posted by Stephen on Sep 13, 2011 in Culture

The Chinese bamboo flute or 笛子 (dízi) is the most popular of the Chinese flutes and woodwind instruments. The versatility and range of the instrument, coupled with the portability and price, makes the dizi easily accessible and useful across many genres of Chinese music. For aspiring musicians, it’s a more refined version of the western “recorder”, but with a sound unlike anything western woodwinds produce.

The Chinese bamboo flute or 笛子 (dízi) is the most popular of the Chinese flutes and woodwind instruments. The versatility and range of the instrument, coupled with the portability and price, makes the dizi easily accessible and useful across many genres of Chinese music. For aspiring musicians, it’s a more refined version of the western “recorder”, but with a sound unlike anything western woodwinds produce.

The dizi is a staple of Chinese folk music, but is also commonly used in Chinese opera and the modern Chinese orchestra. In contemporary and pop culture, the dizi is synonymous with kung fu soundtracks and rock-opera ballads.

Traditionally, the dizi has also been popular among the Chinese common people and thus has earned a reputation as “the people’s flute”. This is in stark contrast to the 古琴, which was reserved for only elite classes (Click here for previous post on the 古琴 or Chinese Zither).

Construction:

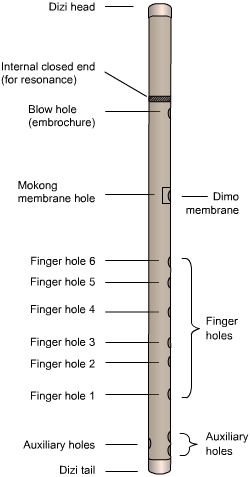

Most dizi are made of bamboo, with the type of bamboo wood depending upon geographical location. Northern Chinese dizi are made from purple or violet bamboo, while dizi (made in Suzhou and Hangzhou) are made from white bamboo. Dizi produced in southern Chinese regions such as Chaozhou are often made of very slender, lightweight, light-colored bamboo and are much quieter in tone. Unlike western flutes, the blow hole is more toward center, and there are six finger holes, with three auxiliary sound holes at the tail of the dizi.

While the type of bamboo influences the sound, the distinct feature of the dizi is the addition of a membrane covered sound hole which, when air passes over it, rattles creating a buzzing timbre, that gives it that signature sound. Thus the dizi is known as the “chinese transverse flute” due to the addition of a secondary “mokong” sound hole. Cover this hole is the “dimo” membrane, which is responsible for this resonating effect on the sound produced by the dizi, adding and amplifying brighter notes, and creating harmonics. As a result, the Dizi has a relatively large range that spans more than two-and-a-quarter octaves.

Sound and Techniques:

Dizi are often played using various “advanced” techniques and relies upon circular breathing or the act of continuously breathing in through your nose and out through your mouth. The dizi, like a western flute, is capable of slides, popped notes, harmonics, finger trills, multi-phonics, and double-tonguing. Most professional players have a set of seven dizi, each in a different key (and size). Additionally, master players and those seeking distinctive sounds such as birdsong may use extremely small or very large dizi, as seen from the video below:

Just listen the amazing range of octaves, trills and almost bird-like sound. The dizi transplants you back in time and out into nature, away from the rumble of car motors and buzz of electricity. It’s an elegant little instrument–both shrill and soothing–that will leave you transfixed. Here’s a more traditional dizi dirge, demonstrating the versatility and range of this mighty woodwind:

Follow Steve on twitter: @seeitbelieveit

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

About the Author: Stephen

Writer and blogger for all things China related. Follow me on twitter: @seeitbelieveit -- My Background: Fluent Mandarin speaker with 3+ years working, living, studying and teaching throughout the mainland. Student of Kung Fu and avid photographer and documentarian.

Comments:

Peter:

The first video reminds me of usual accusations against the Chinese, i.e., instead of enjoying nature, they always want to re-create and surpass it. In the first video,the 笛子 may surpass real bird song, but the effect of the additional drum is not that of thunder to me, but rather the human threat of war in comparison to nature’s happiness. The reason may be that I, as a European, interpret music rather more symbolically, and I feel the utter strive for naturalness in Chinese music as raw in comparison.