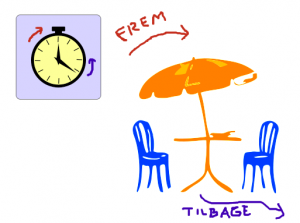

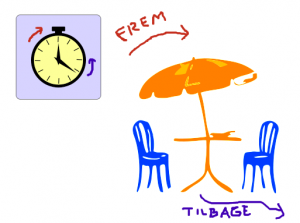

I dag [ee da-y] (today) Denmark went from sommertid (summer time) to vintertid. 12 o’clock became 11 o’clock, as every ur (watch) had to be adjusted by one hour. But in what direction? To solve this eternal problem, the Danes have a saying: In spring, you put your havemøbler (garden furniture) frem (forward, out in the open) – therefore, when going from winter to summer time, the watch should be ”put 1 hour forward”. In autumn, you take your havemøbler back to the basement – accordingly, the time should be ”taken back” by one hour. (Got it? It makes very much sense in Danish! 🙂 )

I dag [ee da-y] (today) Denmark went from sommertid (summer time) to vintertid. 12 o’clock became 11 o’clock, as every ur (watch) had to be adjusted by one hour. But in what direction? To solve this eternal problem, the Danes have a saying: In spring, you put your havemøbler (garden furniture) frem (forward, out in the open) – therefore, when going from winter to summer time, the watch should be ”put 1 hour forward”. In autumn, you take your havemøbler back to the basement – accordingly, the time should be ”taken back” by one hour. (Got it? It makes very much sense in Danish! 🙂 )

Before asking a Dane Hvad er klokken? (What time is it?), there are few things you should know:

- There’s no ”AM” or ”PM” in Denmark. Instead, a 24 hour system is in use in the written language. 23.23 means 11:23 PM, whereas 11:23 AM would be simply 11.23. (In the common spoken language, the hours stop at 12, and if you want to be precise, you’ll have to say things like ’klokken 8 i aften’, at eight (o’ clock) in the evening.)

- There’s no at or o’ clock in Danish. Instead, the word klokken (”the clock”) is put in front of the time: Vi ses klokken ni! (I’ll see you at nine (o’ clock)!) Kampen begynder klokken 19.30. (The match starts at 7:30 PM.)

- There isn’t even a half past! To express the same thing, we kind of imagine that we are walking from one hour to the next. When we’re halfway to ten, we say halv ti (”half ten”) – which of course means half past nine! So, halv syv (”half seven”) would be ”halfway on the journey from six to seven” = 6:30. Got it? 🙂

- 5, 10, 20 minutter i tolv means 5, 10, 20 minutes to twelve; if you’d rather like to say past twelve, over is the word to use: 5 minutter over tolv.

- a quarter to is kvart i, while a quarter past is kvart over: Hvad er klokken? Den er kvart over to. (What time is it? It’s a quarter past two.)

Now, go ahead and ask!

Comments:

Alexandre:

Hello Bjørn,

First, I would like to thank you for this interesting blog, that is a very nice source for every people who would like to learn Danish.

As a French, I particularly like the accents of the Danes so I want to get the basis of the language.

I have a precise question:

I know some verbs can be transformed into nouns thanks to a suffix like -else, -ing or -ning ?

For example, at anse (to consider) becomes anseelse (consideration) and at fodre (to feed) becomes fodring (feeding).

However, are there some tips in order not to make mistakes whle trying to transform a verb into a noun ?

How to be sure it’s begyndelse (beginning) and not begyndning ?

It would be nice to see a post about this aspect, don’t you think ?

Mange tak min ven !

Bjørn A. Bojesen:

@Alexandre Hej Alexandre,

thanks for your nice words! 🙂

I also thank you for your suggestion, it’s a good question and I’ll look into it.

Hav det godt!