The EU, de Globalisering, and the Dutch Language Posted by Jakob Gibbons on Jul 19, 2016 in Dutch Language, News

The summer is off to a shaky start for the European project. For the 27 remaining member states, it’s not only politics and public life that stands to change, but also language, languages, and the balance between them. In the midst of it all, the Netherlands and the Dutch language have front row seats, right in the eye of the Euro-storm.

This post will use Dutch vocabulary related to globalization and international trade that may not be familiar to all readers. Most words are used in context, and there’s a handy woordenlijst at the end.

During the Dutch voorzitterschap of the EU, one of Prime Minister Mark Rutte’s primary goals was assuring that the Netherlands’ strongest ally in Brussels, the UK, was there to stay.

But that didn’t work out so well, to the not-so-subtle satisfaction of some segments of the Dutch media and samenleving.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j1OiBsBtuTk

Since the shocking and disappointing outcome of the referendum across the Channel, Rutte has pointed out in multiple interviews that the Brexit was also an “exit Nederlandse invloed in de EU.”

The reason is more than strictly political—the Brits, and their language, have been an important Dutch ally, in Brussels as well as over much of the several centuries that led up to the European Union and its embrace of globalization.

One of the reasons for this is that compact countries like the Netherlands—with their tiny language and obscure culture and giant multinational corporations—stand a lot to lose in a globalizing world. When money matters are decided in Frankfurt and political ones in Brussels, countries like the Netherlands stand the best chance when they can work with multiple poles of power that keep each other in check and save the little guys from getting trampled.

We already know that, as of now at least, a ‘Nexit’ isn’t likely to have the Dutch following the Brits out the door. So what does await the Dutch language then? For that, a look to the history of de globalisering, de Nederlanden, en de Nederlandse taal.

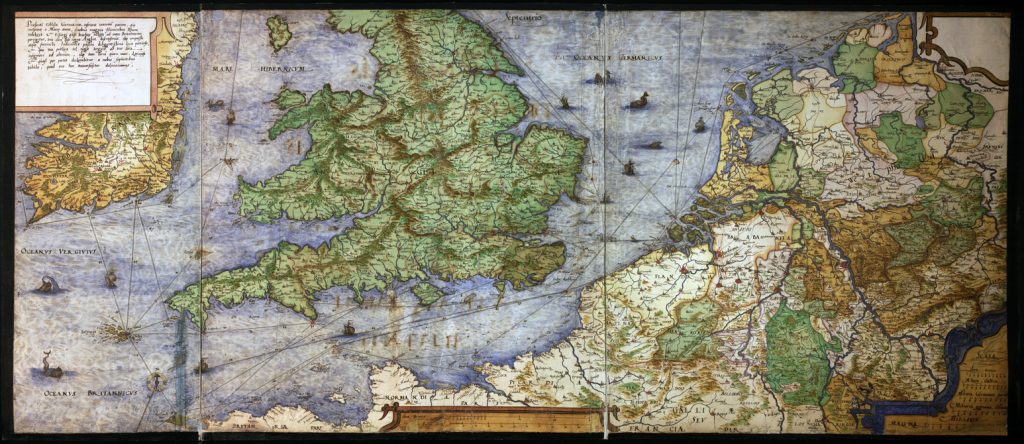

The Low Countries have always been a linguistic and cultural transition zone between English, French, and German. In the 21st century, the characters and plot are mostly the same, but the details get a modern twist. Image by Christiaan Sgroten via Wikimedia Commons under public domain.

The linguistic conundrum of globalization and the Dutch language stands bold in the headline of the 2014 article “De globalisering is verkeerd beheerd” in the Belgian online magazine Mondiaal Nieuws.

This essay on the ‘mismanagement’ of globalization begins with de eerste globalisering—the age of imperialism and colonialism from the 16th to the 18th century—and proceeds through the tweede globalisering of the 19th century Industrial Revolution to put the current age of globalization in context. De derde globalisering, or Third Wave Globalization, describes the familiar modern era of free trade, multinational corporations, and internal single markets and currency unions like those of the EU.

During de eerste globalisering, Dutch companies and colonizers scattered their language across the seas to reach as far as Indonesia, South Africa, and the Caribbean. At the peak of the industrial tweede globalisering, Dutch speakers scattered for a different reason, this time primarily as refugees fleeing the violence of Europe or economic opportunists seeking the then greener pastures of North America. From the 1940s to the 1980s, Dutch-speaking communities took root in places like Canada and New Zealand, as well as across an increasingly interconnected Western Europe.

Het Nederlandse Koloniale Rijk during the first wave of globalization. Many of the shaded areas still speak Dutch or Dutch-influenced languages.

Image by Rex Germanus via Wikimedia Commons under CC0 (Public Domain).

It’s also during Second Wave Globalization that the Dutch language began to adopt a more international vocabulary for talking about the internationalism sweeping through all parts of twentieth century life.

The word globalisering is itself an Anglicism, borrowed from across the Atlantic and put into a popular use that endlessly irked mid-century Dutch linguists. That’s because, if we really want to mierenneuken, the Dutch word globaal (the root of the verb globaliseren) means “op een op het geheel betrekking hebbende verzamelstaat“, or “allesomvattend“; it’s something closer to the meaning of the English word ‘universal’ or ‘general’.

The Dutcher Dutch word for de globalisering has mostly disappeared from popular use, but today you can still find it hidden in the more conservative schrijftaal of Flemish Belgium. In fact, we see it in the name of the magazine I cited at the beginning of this post, Mondiaal Nieuws.

According to the Van Dale, ‘mondiaal’ means ‘over de hele wereld genomen‘, but the form mondialisering is missing from at least the free online version of the Netherlands’ definitive dictionary. Thankfully, however, this linguistic fossil lives on in not only Wikipedia, but also the publications and style books of several prominent nederlandstalige publications.

In their house style book, the NRC Handelsblad points out that while globaal shouldn’t be mistakenly understood as a synonym for the English ‘global’, it is acceptable to use globalisering and mondialisering interchangeably to mean “het wereldwijd worden of maken“.

The conclusion drawn by the NRC Handelsblad, language reference site Taaladvies, and most of the Dutch and Flemish media seems to be the same: de globalisering is a welcome immigrant to the Dutch language, and there’s no particular reason aside from linguistic pedantry for treating it as a second-class citizen alongside the autochtonous Dutch mondialisering.

But at the same time as it embraces the linguistic gifts of globalization, the NRC Handelsblad has called it to task for stifling language’s creative capacity. Several weeks before the Brits voted to Brexit the EU, the Handelsblad published an article titled Neoliberalisme bedreigt veelvormigheid van de taal, lamenting the streamlined and lifeless language that’s emerged in the world of international commerce and the constant pressure to sell.

As I mentioned above, neoliberalism—the economic approach that says multinational corporations and international trade should face as little regulation as possible—is the centerpiece of today’s Third Wave of globalization. It’s also an ideology that, within the European Union, is by far strongest in the United Kingdom, and is espoused in a somewhat more moderate form by the ruling VVD party in the Netherlands. The Handelsblad poses this critique of unrestrained capitalism on the language:

Het neoliberalisme […] tast het vermogen tot verbeelden aan. In samenhang hiermee is de taal homogener geworden. Zakelijker. De wereld wordt beschreven in stereotypen. Zinnen zijn korter […] Er is duidelijk een hang naar formele terminologie en naar een benadering die beschrijft in plaats van bezingt.

The writer of this NRC article will likely see the Brexit as a chance for Dutch and other Europeans to breathe a fresh sigh of relief, but a Neoliberalexit is even less likely than a Nexit. The Netherlands won’t stop trying to buy and sell and trade with the rest of the world, and editors and media producers won’t suddenly be freed from the linguistic constraints of their bottom lines.

Even het neoliberalisme that the NRC criticizes for its assault on language is itself a Latin American linguistic invasion, brought to you by globalization.

Under the 1980s military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet in Chile, Spanish-speaking scholars in Latin America popularized “el neoliberalismo” to describe the oppressive market fundamentalism applied by that regime and imbued the term with the generally negative connotation it carries today. As the economic debate between the North and South raged on, neoliberalismo quickly found its way into the pens and mouths of North American critics as ‘neoliberalism’, and the Dutch neoliberalisme is just one of the many other languages to take up the term across global society.

So in a world where the Dutch’s best bondgenoot has pulled out of the Cool Kids Club and taken its money with it, leaving a thin strip of het Nederlands taalgebied squished between Brussels and a geographic wall of French speakers on one side and the German-speaking financial and industrial heart of Europe on the other—what’s a language to do?

Neoliberalism and globalization won’t go away with the UK: there’s still money to be put in Dutch pockets. The question is, where will it be coming from, and more importantly, what language will it speak? English, French, German… Dutch?

Although satirical newssite Nieuwspaal asserts that Dutch is clearly a good choice for the new voertaal of the EU, that’s not likely to happen. The French, with eyes full of nostalgie, are set on reclaiming their lost linguistic might, and in the opposite direction, the German language and the jobs produced by it suddenly look a lot richer as the second-richest kid on the Euro block packs up and prepares to move out.

What else will happen to the Dutch language without its protective older cousin English peering over the canal to keep French and German at bay? How will the arrivals of thousands of Arab-speaking refugees reshape the urban languages of Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and other multicultural cities?

One of Leiden’s many muurgedichten, this one in Arabic on the side of a café.

The same old mierenneukers who lost sleep over de globalisering surely aren’t fond of de neoliberalisme either, but I think the word, if not what it represents, is a welcome gift from the greater globe.

I think if we can heed the NRC Handelsblad‘s warning, if we can keep neoliberal hebzucht from damaging the creativity and agility that’s allowed globalisering and neoliberalisme into the language, then the future of Dutch looks bright.

De toekomst is helder, en het is zeker globaal, mondiaal, internationaal, en Europees.

Woordenlijst:

- de bondgenoot: partner

- Het Europees Voorzitter: Every six months, one EU member state takes a turn as voorzitter of the Raad van de Europese Unie, the Council of the European Union (also known as the Council of Ministers or Raad van Ministers). The voorzitter leads the assembly of the Council and plays an important role in brokering deals between EU member states.

- de samenleving: society

- de invloed: influence

- globaal: universal, generally applicable; not the same as English ‘global’, which means worldwide

- de globalisering: globalization

- mierenneuken: to nitpick (literally “ant-f***ing”)

- mondiaal: worldwide, across the whole world

- de mondialisering: globalization (a more old-fashioned

- het neoliberalisme: an economic philosophy rooted in the works of Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman and based in the early days of the Cold War. Neoliberalism stresses lassiez-faire free market capitalism and the removal of all barriers to buying and selling, including nearly all government regulation. Currently the driving economic force behind globalization.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

About the Author: Jakob Gibbons

I write about language and travel on my blog Globalect. I often share my experiences with learning languages on the road, and teaching and learning new speech sounds is my specialty.

Comments:

Peter Simon:

A very entertaining and instructive article, thank you.