Ghosts, Ghouls and Goblins Posted by Rachael on Oct 29, 2018 in Hindi Language, Uncategorized

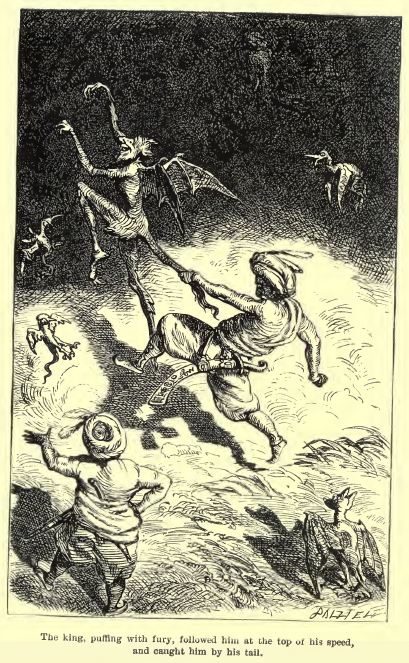

All over the world, each culture has its own ways of making sense of death (मृत्यु or मौत), the afterlife and supernatural phenomena. India, of course, is no exception. In my last blog, I discussed the tales from Baital Pachisi (बेताल पच्चीसी), a collection of stories about the mythical king Vikramaditya and his quest to capture a baital, a supernatural creature that is extremely cunning and makes its home in cremation grounds. In addition to this, there are numerous stories of other supernatural creatures (अलौकिक प्राणी) that challenge the boundaries (सीमाएँ) drawn in everyday life between the “real” (वास्तव) and the “unreal” (अवास्तव).

Depending on the version of Baital Pachisi you read, the baital is sometimes described as a pisacha (पिशाच), or a demon of dark complexion with prominent veins and bulging red eyes that feasts on flesh and, like the baital, lives in cremation grounds. The baital, on the other hand, although sometimes described as a hideous (भयंकार) creature, can also be more ghost- or spirit-like in that it possesses the ability to reanimate corpses (लाश or शव). Once the baital’s spirit has assumed the body of the corpse, the corpse ceases to decay and the creature is able to use it as a vehicle for movement. Yet, the baital is not tied to any particular body and can leave the corpse at will (अपनी मर्ज़ी से).

As for pisachas, they live alongside ghosts (भूत) and baitals in cremation grounds, but they have the ability to change their form (रूप) at will and even become invisible (अदृश्य). They are particularly sinister because they feast on human energy and can even possess a human being with the capacity to drive their “host” insane (पागल). Certain mantras (मंत्र) or religious chants are said to have the power to free a possessed person of the presence of a pisacha but, in order to prevent this from happening in the first place, religious offerings (प्रसाद) are made to these spirits during certain festivals.

Concerning bhoots (भूत), we are very familiar with these spirits from Western folklore (लोक कथाएँ) and mythology (पौराणिक कथाएँ), which imagines these beings as similar to their Indian counterparts. A “bhoot” or ghost mainly serves as a warning (चेतावनी) to society that those who encounter a violent end, those who die leaving pressing business unfinished and those who do not receive proper, religiously-sanctioned burials (दफ़न, an actual burial, not practiced by Hindus vs. अंतिम संस्कार, the last rites, including cremation, paid to a Hindu in death), will come back to plague the living. This is not only a warning for mourners, who must ensure a proper burial to put the dead truly to rest, but also for every mortal being, as the ghost him or herself is figured as a restless (बेचैन), tormented soul, either because of a violent death that could have been avoided or because they lacked the foresight in life to seize the moment.

One famous “bhoot” appears in the film Paheli (पहेली, 2005) and its predecessors. It is the story of a woman, Lachchi, who is newly married to a rich merchant (अमीर व्यापारी), Kishan (or Krishanlal in other versions) in the vast stretches of the Rajasthani desert (रेगिस्तान) who must reckon with her husband’s cold concentration on business matters above all else, his strict accordance with his father, a business magnate’s, wishes and lack of concern for his family and, especially, new bride (नयी दुल्हन). In fact, on the day after their wedding, he sets off into the desert to start a new business faraway, not to return for five years; in the meantime, his wife falls in love with a ghost who assumes the form of her husband, having glimpsed her before her marriage and falling in love with her instantly. The ghost tells the woman of his true nature, but that does not deter her from loving him. The real problem (असली समस्या), however, arises when her real husband returns from his business trip to find his wife pregnant. This film is in turn based on director Mani Kaul’s Duvidha (दुविधा, 1973), which is itself based on a short story by renowned Rajasthani storyteller Vijayadan Detha (also known as Bijji).

Interestingly, unlike Western tales that often imagine a dark spirit or creature as existing wholly apart from humanity (मनुष्यता) – as the opposing, negative (नकारात्मक) force to humankind’s essential goodness – dark or supernatural beings in Hindu mythology are often conceived as having an origin not unlike our own whose lives at some point went awry and as existing alongside us, even in daily life, as integral aspects of the human experience. In Detha’s “Duvidha,” and the film versions of it, the ghost is not imagined as the restless, tormented soul of a deceased person, but as a spirit or supernatural creature that has the ability to shape shift and thus toy with humans’ perceptions of reality (असलियत or वास्तविकता).

In the many versions of “Duvidha,” the real Kishan is portrayed as cold, heartless and even mechanical (मशीनी) in his actions and speech, a much less human form of the more desirable alternative (विकल्प): the ghost, who is ironically more sensual, emotive and exuberant than his living counterpart. The ghostly “version” of Kishan challenges the business-oriented family’s priorities in life and the ghost even pokes fun at the cold materialism of Kishan’s father by magically generating gold coins (सोने के सिक्के) to keep him pacified. The riddle or dilemma (paheli/पहेली, duvidha/दुविधा) comes in to the story in that Lacchi, the bride, is presented with a dilemma between her flesh-and-blood, lawful husband who is nevertheless cold and almost inhuman and his ghostly counterpart, who seems more alive and real than most of the other humans she knows.

The following is a song from the 2005 film (Paheli) that playfully features the sound of bangles (चूड़ियाँ), a symbol of the marital state, tinkling (खन खनननन and छन छनननन) and the “kangana” (कँगना or a string or thread tied around the right wrist of the husband and the left wrist of the wife by a priest on their wedding day) as a symbol of the “suhag raat” (सुहाग रात) or first night passed together as husband and wife. In this song, the sound of bangles tinkling is a symbol not only of feminine beauty and fulfillment but also a happy marriage.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.