Levels of Language: Register in Hindi, Part 3 Posted by Rachael on Dec 29, 2017 in Hindi Language, Uncategorized

In today’s post, I’ll be discussing the newest transformation that Hindi has undertaken: Hinglish. This term refers to a combination of Hindi and English vocabulary, syntax and, sometimes, grammar and idiom. It can refer to speech that includes a vast majority of English and a minority of Hindi or vice versa. But, for the purposes of this Hindi blog, I will primarily discuss Hinglish that encompasses a majority of Hindi and a minority of English.

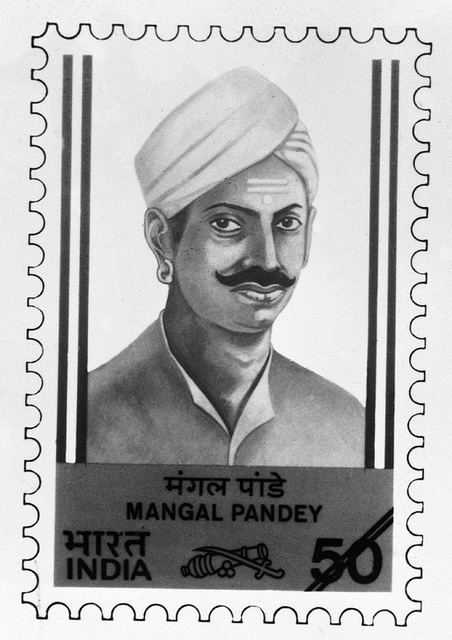

English has been present in India for centuries, so it is not surprising that it has now made its way indelibly into many Indian languages, including Hindi. Since the British East India company set up shop in India around 1600, English was being spoken (and learned) in various parts of India where the company was active. After India’s First War of Independence in 1857 (variously called the “Sepoy Mutiny” and “The Indian Rebellion of 1857,” amongst other titles), the British crown took over for the British East India Company and India became one of the many “jewels” in the crown of Queen Victoria. Of course, colonists from England and nearby countries (including Scotland, Ireland and Wales) had been traveling to and settling in India long before the British crown took control of it: they served as missionaries, teachers and professors, members of the Army and as administrators and rulers for the British colonial government.

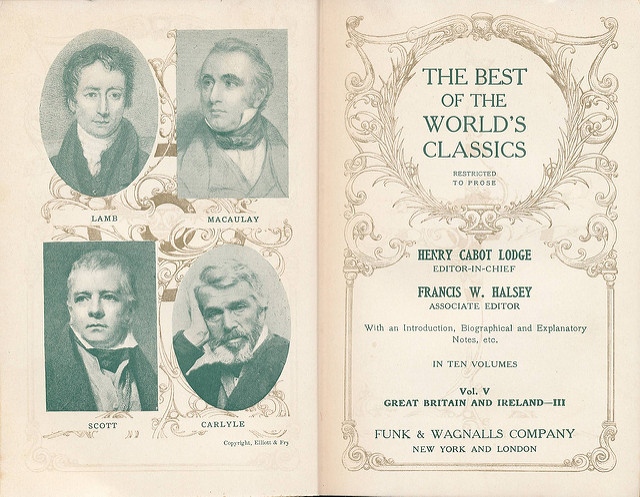

One of the most infamous tracts on the “superiority” of the English language and the need for its greater dissemination in India in order to train a “new class” of Indians who were Indian on the outside, but British on the inside (in terms of culture and education), who could serve as able civil servants for her Majesty, was written in 1835 by Thomas Macaulay, a British historian and politician in India. In this minute, (read it here), Macaulay advocated for the abolishment of Indian education in classical languages, such as Sanskrit and Arabic, which the British government paid Indians to study in the form of fellowships (as knowledge of these languages did not lead to profitable jobs at the time). Instead, he asserted that the British government in India should advocate greater knowledge of English in order to better train Indian civil servants and, eventually, to “Indianize” the civil service in order to move India incrementally toward a preparedness for Independence (this latter idea, however, would come later).

Of course, the view that English is somehow “superior” to any Indian language is not only outdated and outlandish, but bigoted in the worst possible way. However, since India achieved its independence in 1947 and the country’s economy was liberalized in the early 1990s to welcome foreign investment and the greater Western influence on Indian culture that accompanied it, English has indeed held a position of prominence and prestige that, while not reflective of colonial “Anglophilia” per se, leads one to question the role that indigenous languages will play in an increasingly globalizing world in which English, for better or worse, is the lingua franca. As stated in my previous blogs about “register” (read parts 1 and 2) in Hindi, Hinglish is most common amongst the younger, wealthier, more educated and more mobile demographic of Indians, although it is certainly present to a great extent amongst older generations. One’s participation in Hinglish is, in some ways, a status symbol of one’s greater knowledge of English. Today, English is a language often associated with ambition, success, wealth and higher socioeconomic status, as a knowledge of English is often necessary to take part in high-prestige jobs that grant greater socioeconomic mobility in India and elsewhere.

On the other hand, however, Hinglish can be seen as a revolt against the colonial and postcolonial hegemony of English as can be seen in the name itself: it is not only a celebration of English, but of Hindi as well. It celebrates the blend of both languages, rather than the dominance of one language over the other. On the flip side, the presence and popularity of “Indian English” novels, such as those of Chetan Bhagat, suggests a pride in one’s identity as a moderately educated Indian from a Tier II or III city who is not afraid to celebrate one’s difference in being Indian rather than entirely “Westernized.” Although “Indian English” is obviously different from Hinglish in that it acknowledges the dominance of English, the unabashedly “non-standard” way in which the characters in these novels speak and think suggests an embrace of an inescapable reality while at the same time creatively molding that reality (and that language) to suit one’s own ends. Yet, the danger of Hinglish comes in the phenomenon of devaluing and perhaps even forgetting certain Hindi words and phrases in the process of privileging a high-status language such as English. Such a phenomenon is evident in some urban Indian youth’s insistence on saying things like “Sunday को/ko” and “Wednesday को/ko” rather than the equally simple “रविवार को/ravivaar ko” and “बुधवार को/budhvaar ko.”

Regardless of the positives and negatives of the Hinglish “pidgin,” a knowledge of it is essential in order to claim any degree of fluency in Hindi as it is spoken today and as it continually evolves, shedding old words in order to adapt to a modern world. Let’s look at an example of Hinglish in the dialogue below:

प्रिया: चल यार, तूने बता पहले कि आज रात को हम मूवी/movie देखेंगी । कौनसी टाइप/type की पिक्चर/picture देखनी है तुझे ? (Chal yaar, tune bataa pehele ki aaj raat ko hum movie dekhengee. Kaunsi type ki picture dekhni hai tujhe?)

Priya: Come on, yaar (friend), you said before that we were going to watch a movie tonight. What kind of movie do you want to see?

आयशा: मुझे नहीं पता यार, आज कल मैं बहुत टेंशन/tension में हूँ । ऐप/app के through वह लड़का जिसके साथ मैं छैट/chat कर रही थी, याद है…परसों उसने मेरे से छैटिंग/chatting करना छोड़ दिया । नहीं मालूम…कया करूँ ? (Mujhe nahin pataa yaar, aaj kal main bahut tension me hoon. App ke through voh larkaa jiske saath main chat kar rahi thi, yaad hai…parson usne mere se chatting karnaa chor diyaa. Nahin maaloom…kya karuun?)

Aisha: I don’t know yaar, I’m very tensed (worried) these days. Do you remember that boy I was chatting to through the app (dating app)? He stopped chatting with me the day before yesterday. I don’t know…what should I do?

प्रिया: अरे यार, छोड़ दे उसको! क्या बकवास है, सेंटी हो गयी है क्या? उसकी क्या परवाह, वह इतना खूबसूरत भी नहीं था । चल, मैचेज़/matches को देख लें, तेरे लिए ज़्यादा सुन्दर लड़का जल्दी मिल जायेगा । (Are yaar, chor de usko! Kyaa bakvaas hai, senti ho gayi hai kyaa? Uski kyaa parvaah, voh itnaa khoobsoorat bhi nahin thaa. Chal, matches ko dekh len, tere liye zyaada sundar larkaa jaldi mil jaayegaa).

Priya: Oh, yaar, forget about him! What kind of nonsense is this, have you gone soft (sentimental)? Why do you care about him, he wasn’t even that handsome. Come on, let’s look at your matches, we’ll get you a cuter boy really quick.

आयशा: लेकिन वह बस हॉट/hot नहीं था, बहुत अच्छा बात करता था और बहुत स्वीट/sweet भी लगता था…वह बहुत पसंद था मुझे । (Lekin voh bus hot nahin thaa, bahut acchaa baat kartaa thaa aur bahut sweet bhi lagtaa thaa…voh bahut pasand thaa mujhe).

Aisha: But he wasn’t just hot, he talked very well and he seemed sweet too…I really liked him.

प्रिया: अरे उल्लू का पट्टा ! अपने आप बेवकूफ़ मत बना ! लड़के तो लड़के ही हैं, भगवान नहीं । मैं तो हर हफ़ते दूसरे लड़के के साथ डेट/date पे जाती हूँ । (Are ullu kaa pattaa! Apne aap bevakoof mat banaa! Larke to larke hi hain, bhagvaan nahin. Main to har hafte doosre larke ke saath date pe jaati huun).

Priya: Oh you idiot! Don’t make yourself a fool! Boys are just boys, they’re not God. I myself go on a date with a different boy every week.

आयशा: सच!? ऐसे कैसे कर सकती है तू? लव/love में (या प्यार में) कभी नहीं गिरी है अभी तक? (Sach!? Aise kaise kar sakti hai tu? Love me (ya pyaar me) kabhi nahin giri hai abhi tak?)

Aisha: Really!? How can you do such a thing? Haven’t you fallen in love yet?

प्रिया: नहीं नहीं, बक्वास मत कर । लव/love को तो वेट/wait करना पड़ेगा ! ये इडियत/idiot वाले लड़के टाइम पास/time pass के लिये ही हैं । (Nahin nahin, bakvaas mat kar. Love ko to wait karnaa paregaa! Ye idiot vaale larke time pass ke liye hi hain).

Priya: No, no, stop this nonsense. Love will just have to wait! These idiot types (boys) are just for passing the time.

आयशा: अच्छा, समझी गयी । लेकिन, मैं तेरे जैसे नहीं बन सकती, तुझे पता है । (Accha, samajh gayi. Lekin, main tere jaise nahin ban sakti, tujhe pataa hai).

Aisha: Ok, I get it. But, I can’t be (or become) like you, you know.

प्रिया: हाँ, हाँ, मुझे पता है उल्लू (rolls her eyes) । तुझे तो मज़े करना नहीं आता, न ? (Haan, haan, mujhe pataa hai ullu. Tujhe to maze karnaa nahin aataa, na?)

Priya: Yes, yes, I know you idiot. You don’t know how to have fun, do you?

आयशा: (laughs, mock offended) अरे क्या कहा, चुप कर ! मैं तुझे दिखाऊँगी ! मैं रैंडम/random से एक लड़का choose/छूज़ करूँगी और उस के साथ डेट पे जाऊँगी कल रात को ! (Are kyaa kahaa, chup kar! Main tujhe dikhaaungi! Main random se ek larkaa choose karuungi aur us ke saath date pe jaaungi kal raat ko!)

Aisha: Oh, what did you say, shut up! I’ll show you! I’ll randomly choose a boy and go on a date with him tomorrow night!

प्रिया: अच्छा, दिखा दे उल्लू! लेकिन randomly नहीं चुनना, उसे तो बहुत हॉट होना चाहिये (laughs) । वैसे, आज रात के लिये हमें लड़कों को छोड़ना है ‑‑‑कयोंकि मूवी देखनी है आज! क्या क्या देकनी है? (Accha, dikhaa de ullu! Lekin randomly nahin chunna, use to bahut hot honaa chahiye. Vaise, aaj raat ke liye hume larkon ko chornaa hai—kyoonki movie dekhni hai aaj! Kya kya dekhni hai?)

Priya: Ok, show me idiot! But don’t randomly choose, he should be really hot! Anyways, let’s forget about boys for tonight—because we’re going to see a movie! What do you want to see?

Quiz Yourself! Can you think of the Hindi alternatives to the English words listed below? (Answer key underneath):

- Movie/picture

- Type

- Tension

- Through

- Chat, talk

- Sweet

- Love

- To wait

- Problem

- Right, left

Answers:

- फ़िल्म/film (fem. noun), चलचित्र/chalchitra ( noun, very rare)

- तरह/tarah (fem. noun), क़िस्म/kism (fem. noun)

- तनाव/tanaav (masc. noun)

- के ज़रिए/ke zariye (postposition), के माध्यम से/ke maadhyam se (ppn., less common)

- बात करना/baat (fem. noun) karnaa, बातचीत करना/baatchit (fem. noun) karnaa, गुफ़्तगू करना/guftagoo (fem. noun) karnaa, वार्तालाप करना/vaartaalaap (masc. noun) karnaa (less common)

- मीठा/meethaa (not often used for disposition of a person), मधुर/madhur, सुशील/susheel

- प्यार/pyaar (masc. noun), प्रेम/prem (masc. noun), मुहब्बत/muhabbat (masc. noun), इश्क़/ishk (masc. noun)

- इंतज़ार करना/intazaar (masc. noun) karnaa

- समस्या/samasyaa (fem. noun), मुसीबत/musibat ( noun), मसला/masala (masc. noun)

- दाहिना/daahinaa, बायाँ/baayaan

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

Perrin:

Great article. From what I’ve seen so far the power balance between Hindi and english is clearly in favour of English, as words being left behind are Hindi words and not english ones and what an unfortunate loss it is …

Rachael:

@Perrin Hi Perrin,

I’m so glad you enjoyed this blog! Yes, I would agree with you that this, on the whole, appears to be the case. But, Hinglish is not entirely devoid of interesting elements, as we can see with the “Hindization” (or, sometimes, “Indianization”) of certain English words (पंचर/panchar and सेंटी/senti being two that come to mind).

Rachael

Perrin:

@Rachael Yes you’re right plus some sources from the oxford english dictionnary shows that more than 80 words from India have made their way to english, in the dictionnary !

I have a very technical question about spelling in devanagari also and hope you’ll be able to help me with it 🙂

here it is : I’ve got to know a long ago that we westerners tend to add extra “a’s” wherever we can for hindi/sanskrit nouns (artha, karma, mantra, sutra, rama etc.)

So what I wanted to do is to check the devnagari version of the word to get the correct pronunciation but the use of halant -really important here- is missing…

basically the problem is that सवाल should technically be prounounced as “sawaala” as there’s no halant on the ल, but even without, everyone knows it is actually “sawaal” so no Halant there.

But if you check the wiki page for “Rama” which is actually “Ram” (I know this from Hindi native speakers) it is still written राम which is “Rāma” and not “Rām”as there’s no halant

So how could I know from the Devnagari version of the word how it is supposed to be prounced when no one uses the halant ? if the last character implies a अ or nothing at all

thanks for reading my existential question

Rachael:

@Perrin Hi Perrin, no problem! It seems that a lot of the confusion can be cleared up when considering word origin and vowel morphology. The words you mentioned above are almost all from Sanskrit; according to Sanskrit rules of pronunciation, pronouncing these words with an ending “a” sound is the CORRECT way to pronounce them. However, this is mostly not the case with Hindi:

SANSKRIT pronunciation: HINDI pronunciation:

artha arth

karma karm

mantra mantra (exception)

sutra sutra (exception)

Rama Ram

Mahabharata Mahabharat

Ramayana Ramayan

Ganesha Ganesh

Shiva Shiv

Although Sanskrit and Hindi are related languages, they have some very important differences between them and are, in the end, distinct and separate languages. Here you can see that, in the Hindi pronunciation of these words, the ending “a” has been mostly dropped in pronunciation with no halant needed because the implication is that Sanskrit rules of pronunciation do not apply to Hindi words here. In fact, according to Hindi rules of pronunciation, the ending “a” (also called the inherent vowel present in ka, ba, bha, pa, etc.) is almost always dropped at the end of a word, whereas this dropping does not occur in Sanskrit. However, there are important exceptions: it is easy to pronounce the word “arth/a” without the final “a” but words like “sutra” and “mantra” with an ending “tra” would be next to impossible to actually pronounce without the final “a” sound, so it is therefore morphologically NECESSARY to include those final “a” sounds.

Lastly, a word like “savaal” is actually from Arabic, so the rules of pronunciation that govern other Hindi words and Sanskrit words especially do not apply here (there is no notion of an ending “a” in Arabic as there is in Sanskrit). Therefore, you also don’t need a halant because the ruling assumption is (with a few exceptions) that most Hindi words do not end in an “a” sound (as distinguished from a long “aa” sound).

I hope this helps!

Perrin:

@Rachael Wow you perfectly answered my question and what I could possibly wonder, thank you so much !