Vikram and The Vampire / विक्रम और बेताल Posted by Rachael on Oct 27, 2018 in Hindi Language, Uncategorized

As Halloween is one of my favorite holidays (मनपसंद त्योहार/manpasand tyohaar), and I’ve been fascinated with ghost stories since I was a child, I thought I would share an Indian “ghost story,” if you will, in honor of the upcoming (आनेवाला/aanevaalaa) holiday. When I was a teenager, I came across a collection of tales (कथाएँ/kathaaen or कहानियाँ/kahaaniyaan) called Baital Pachisi (बेताल पच्चीसी) or, in Sanskrit, Vetala Panchavimshati (वेतालपञ्चविंशति) that thoroughly captivated me. Although originally in Sanskrit, this collection of tales has been translated into a variety of Indian vernaculars, such as Hindi, Tamil, Bengali and Marathi, and has had a long life in terms of its many translations and retellings (including in English) and its numerous adaptations for the screen in the form of serials (TV shows). Its legacy lives on today in popular culture (लोक संस्कृति/lok sanskriti), although its historical roots (ऐतिहासिक जड़ें/aitihaasik jaren) and literary saga (साहित्यिक कथा/saahityik kathaa) are perhaps more fascinating.

बेताल पच्चीसी, which means “The Twenty-Five Tales of Baital,” is a collection of stories within a frame (or overarching) narrative about a king (राजा/raajaa) and his quest to capture a “baital” (often rendered as “vampire” in English although the reality, as you’ll see, is more complicated) in order to receive a boon (वरदान/vardaan) from a powerful tantric sorcerer (वामाचारी/vaamaachaari=literally means “practitioner of left-handed doctrine” because it is opposed to orthodox or normative Hindu practice). The oldest revised edition of these tales appears in the 12th book of the Kathasaritsagara (कथासरित्सागर, or Ocean of the Streams of Stories), a Sanskrit work compiled in the 11th century by Somadeva that was based on (आधारित पर/aadhaarit par) older materials no longer available. The English translations we have now are based on Sanskrit as well as vernacular renderings, but perhaps the most well-known of these is a version published in 1870 by Sir Richard Francis Burton, who did not attempt a faithful translation (अनुवाद/anuvaad) but rather a loosely-based retelling.

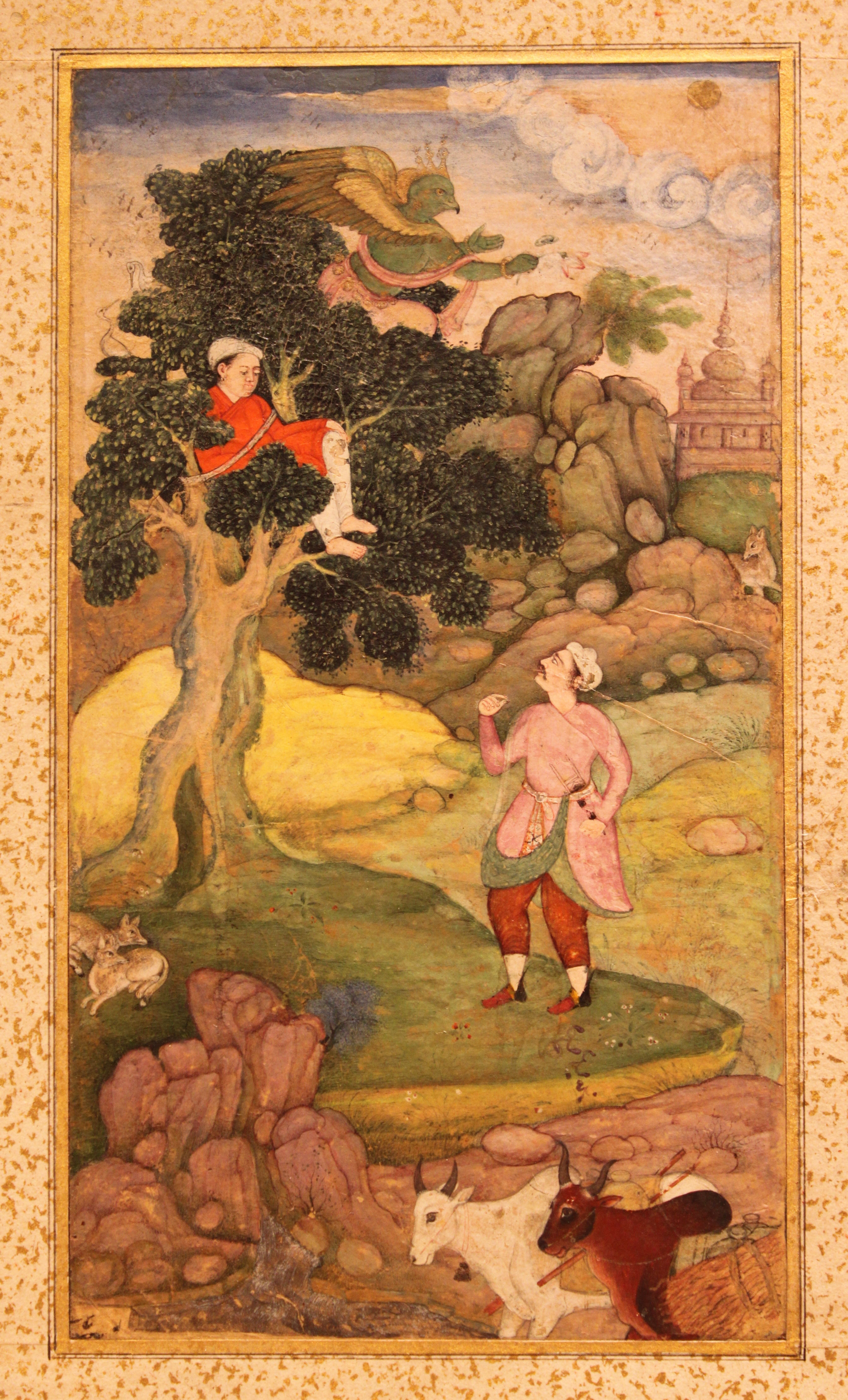

The story goes that there was once a renowned king named Vikramaditya (विक्रमादित्य, also known as Vikrama) who promised (वादा करना/vaadaa karnaa) a वामाचारी (powerful tantric sorcerer) that he would capture a baital (also called vetala in Sanskrit) for him. A baital, if you’re wondering, is a creature that is somewhere between a ghost, vampire and zombie. Most likely, “baital” is so often translated into English as “vampire” because most of the English translations and retellings we have now are from the 19th century, when straight-laced English society (अँग्रेज़ी समाज/angrezi samaaj) was gripped by a fascination with seductive vampires, with Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla published (प्रकाशित हुई/prakaashit hui) in 1871 and Bram Stoker’s Dracula appearing in print in 1897. Another reason is, of course, the unique nature of the “baital” and the lack of a direct parallel in English and Western mythology.

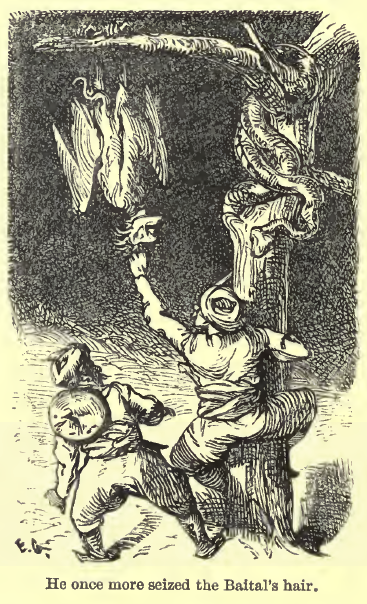

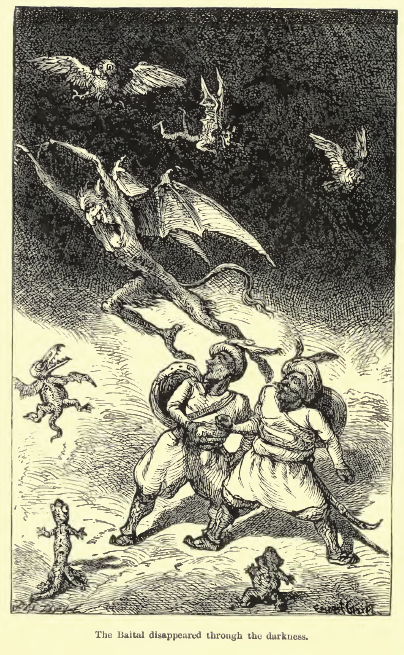

The baital lives, as they are wont to do, in a cremation ground (श्मशान/shamshaan), where it hangs upside down from a tree. The story revolves around Vikramaditya’s attempts to capture the baital and the baital’s attempts to escape by telling Vikramaditya a series of stories that end in riddles (पहेलियाँ/paheliyaan). The pact between the king and the baital is that, if Vikramaditya cannot come up with the answer to the riddle, the baital will gladly be handed over to the sorcerer, thus awarding Vikramaditya’s ignorance and perhaps humility (विनम्रता/vinamrataa). In addition, there is a consequence to Vikramaditya’s knowing the answer and remaining smugly quiet – his head will burst open. Lastly, if the king answers correctly, the baital will continue to evade capture, thus punishing him for his knowledge (ज्ञान/gyaan) and arrogance (घमंड/ghamand). As you can see, the baital is portrayed as a cunning (चतुर/chatur) creature in the story, as he devises a means by which the king’s knowledge, for once, does not serve him well and the odds are generally in the creature’s favor. Fortunately for the baital, the king knows the answer to every question posed to him, resulting in 24 tales. Yet, at the close of the 25th tale and the presentation of the riddle, the king is truly defeated (हार खाई/haar khaayi) and thus the baital consents to be taken to his new “master.” But, the drama doesn’t end there as the sorcerer is not quite who he says he is.

This story’s saga in Hindi began in the early to mid 1700s, when Surat Kabishwar translated Sivadasa’s early Sanskrit version of the collection into Braj Bhasha (ब्रज भाषा), which was subsequently translated into Hindustani (हिंदुस्तानी) in 1805 by Lallu Lal and others under the direction of John Gilchrist. As such, this work played a pivotal role in the development (विकास/vikaas) of the language we recognize today as Modern Standard Hindi. In fact, this story was even used as a means to test (परीक्षा/parikshaa) military service students on their Hindustani proficiency (दक्षता/dakshataa) in the East India Company.

If you’d like to check out a screen version of these tales, you can watch director Prem Sagar’s Vikram aur Betaal (विक्रम और बेताल), which was first aired in 1985 as a television serial on India’s popular public TV network, Doordarshan (दूरदर्शन). This serial was remade by the channel Colors, again backed by Sagar Films, as Kahaniyaan Vikram aur Betaal ki (कहानियाँ विक्रम और बेताल की, The Stories of Vikram and Betaal).

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.