English cognates and slang in Icelandic Posted by sequoia on Apr 14, 2012 in Icelandic culture

There’s lots of English slang in spoken Icelandic, and a bit less in written. (EDIT: Please see Alex’s comment for notes about “cognates” and “false friends”, etc. as well as good examples!)

In person Icelanders, when chatting with friends, might use straight English words for things that may not exist in Icelandic, that have a more complicated Icelandic word, or as some sort of in-joke. I’ve also heard a lot of phrases both said and (casually – like on Facebook comments and forums) written entirely in English in the middle of an Icelandic conversation. In books people tend to use more proper Icelandic.

Example: Páskaöl: basically Jólaöl nema bara í öðrum umbúðum. / Easter (that orange soda and malt drink I mentioned before): basically (Christmas version of the exact same thing) but just in different packaging.

“Lengsta “alvöru” orðið (as in eitthvað sem er actually…” / The longest “serious (real)” word (as in something that is actually…”

Here are some more examples, sorry but I don’t know the most common/useful words so I just listed random ones (note that if your dictionary says something else I’d trust it instead – the online dictionary I use can sometimes be off):

fésbok – Facebook

júróvision (also “Söngvakeppni”) – Eurovision

sjoppa – shop (mini kiosk, etc.)

sorrý – sorry

bingó – Bingo

krem – cream mixed with something like eggs, colouring, flavouring (ex. chocolate mixed in with cream is súkkulaðikrem), also it means “paste” in toothpaste, it can mean ointment, etc. As far as I know we don’t have a single word for this.

massi – mass

stíft – stiff, stubborn, stand-offish

smyrja – sounds similar to”smear”, spread, grease, butter (but apparently can mean doing it thickly too, ex. layer frosting over a cake)

konfekt – confectionary

pottur – pot, liter, chamber pot, hot tub

binda – tie, bind

karamella – toffee, caramel, also used for chewy flavoured candies with the consistency of either of those

tóbak – tobacco

gólf – floor

vanilja – vanilla

djók (also “grín”) – joke

prenta – print

bókband – book binding

Bann – ban

Smella (only when talking about online, it has other meanings) – click

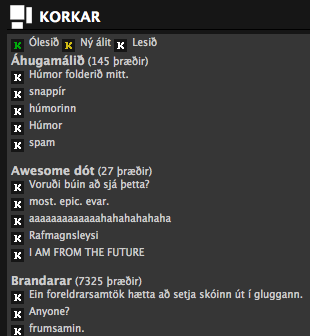

Screenshot from hugi.is, as you can see some people like to use casual, random English – but this doesn’t mean their thread is in English. To illustrate what I mentioned above, “folder” (even the “computer folder” meaning) has an Icelandic word, so does “awesome”, and certainly “anyone” does too. Sorry but I don’t have more examples for you because most things I have saved were written by friends and I don’t want to copy them even if it’s not private.

Here is a link to Snara.is’ online slang dictionary. There was also at least one slang dictionary published but I hear it’s bad and out of date.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

About the Author: sequoia

I try to write about two-thirds of the blog topics on cultural aspects and one-third on the language, because there's much more out there already on the language compared to daily life information. I try to stay away from touristy things because there's more of that out there than anything else on Iceland, and I feel like talking about that stuff gives you the wrong impression of Iceland.

Comments:

Alex:

Cool post!

It is a bit of a confusing mess of what’s traditional Icelandic and genuinely a Germanic cognate and what else is a direct adoption or a calque (loan-translation). The calques are generally regarded as tainting the language for some people. I think Icelanders call these words “sletta” (or rather, “slettur”) to show a foreign word.

I have spoken with people in colloquial senses and they’ve said “mappa” for “folder”, though I guess I shouldn’t really be surprised 😀

There is a distinction between cognates and false friends though. False friends generally have no historical connection, and it’s just a chance similarity, which means (as the Swedish article says) that “bra” (brjóstahaldari) can look like “bra” (gott). Cognates can look the same and be similar (binda/bind, drykkja/drink, stinga/sting) but it’s the historical connection that matters.

So our English word “silly” is cognate with the “sæl(l)” that you use to greet people with. It went through a big semantic change in English and meant innocent, then weak, then childish, then stupid. Icelandic retains the “blessed” meaning, which is the greeting form.

Usually, if there’s even a chance that something sounds archaic in English you can tell it’s a cognate, like “clad” (klæddur).

An interesting double example is with “girlfriend” and “whore”, which both come down from the same root. One comes from Latin and didn’t have the Germanic shift from k-initial words to h-initial words. So in Italian there is “caro” [ka:ro] and English and Icelandic have cognates ‘whore’ and ‘hóra’ respectively, but Icelandic borrowed Danish ‘kæreste’, which borrowed that from a Latinate language (not sure exactly which one), and therefore another cognate comes into the mix, this one from a non-Germanic root because it starts with a [k] sound.

So other archaic things you can see are:

biðja / bað – bid / bad.

dalur – dale (valley)

halda – hold (I hold(think) that he…)

smyjra – smear (like you said).

fara – fare (fare well = go well)

That’s actually how I remember the word, because it’s linked to smjör (butter) and you can think of smearing butter on a piece of bread. They’re cognates as well.

Also, if you see a nk(g)/nd in English that becomes kk/tt in Icelandic, that’s another sign of a cognate. Old Norse turned all n+k/t sounds into a doubling up of the consonant, so you get past tense endings like:

binda / batt

bind / binded

stinga / stakk

sting / stung

springa / sprakk

spring / sprung.

Hopefully that might give some people a better understanding of the relationship.

Though, when you see Icelanders say stuff like: það meika bara ekki séns, it probaby can look like ‘meika’ is a cognate, but it’s just an Icelandicised spelling, like when they write:

osom = awesome

djók = joke

ómægat = oh my god

etcetc…

sequoia:

@Alex Oh no! I was just sitting down to edit the “cognate/loanword/false friends” bit because my wife and Wikipedia taught me a bit more about them, but I see you got to the post first. Instead of re-writing it then I’ll just edit the post to tell people to read your comment. : Þ

Thanks a lot, I especially don’t know much from a historical or linguistics side (all I know are bits people and teachers have told me – I’m just a regular language learner and have never studied older languages either). When I was in America learning languages they also never taught me anything like that, including anything beyond basic vocabulary for grammar terms (we never learned “subjunctive” for example, just “this is how you say this”). So I’m glad at least one person knows what they’re talking about haha.

Kenneth S. Doig:

@Alex Finally, someone who knows what he’s talking about when ur comes to Gmc & IE philology, etymology, phonology.

Alex:

😀

Yeah, it is really interesting. I was the same when I started learning Italian about 7 years ago, an 18 year old monolingual English speaker with absolutely no idea what even a “noun” meant, let alone subjunctive and grammatical moods. But, as you can see, the more I learnt about it the more I got into it, which eventually put me on the path to do a degree in Linguistics. It’s really odd when you can pinpoint how your life changes after one incident in the past. I remember first picking up the red advert advertising lessons that made me sign up to a class. That one decision has put me on the path to learning Icelandic and wanting to do a degree there. Madness! I wonder where I would be if I had never seen that red piece of paper that came through the letterbox (frightening thought!)

The problems with linguists is they can generally talk about a language at length for hours, know its history, structure, and even a lot of words, but basic conversation in a consistent way escapes them. That’s my problem at the moment. I lack the regular use and corrections, which I’m hoping to build up when I fly out there in the summer.

So someone with the basics and the confidence to talk to a stranger in the street and not have a good linguistic understanding is still someone I envy! I just lose the ability to separate out Italian and Icelandic when I talk. I had to ring the Thjodhatid office and Herjolfur last week and I kept saying “grazie” and ended the conversation with “ciao”. It was quite embarrassing that I couldn’t control what I was saying due to the lack of confidence.

It took me about 10 mins to mentally plan how to ask for a drink on the plane when I flew out last year. The irony is I met the President at Gatwick Airport and he was the first real Icelander I had a proper conversation with, which is quite strange.

sequoia:

@Alex I just recently found out that a degree in “philology” exists (a subject I’d never even heard of before – I had only heard of more general things like “linguistics” as a whole) and that’s something my wife is really interested in, especially concerning the Nordic languages. I actually have a small post about Faroese and Icelandic that will be posted in some time (it’s scheduled to be posted sometime in the next few weeks – I set things to elapsed posting now) but since the books I’ve gotten that explain some etymology and language history clearly are actually in Swedish, which I can’t read well yet and I’m not about to force my wife to paraphrase an entire book, I won’t be mentioning much. It’ll kinda be like this post here, “look! some similar words!”.

Not knowing grammar terms was actually the biggest issue I had when starting to learn Icelandic. All my textbooks just threw out stuff like “cases” all at once, when not only did I have no idea what a case was, I couldn’t find a clear explanation of them online either. I literally spent months not knowing why there were cases or when you used them, and then I couldn’t study anything. That’s part of why I try to over-explain things on this blog (and in my textbook, once it eventually gets finished) because I am definitely one of these people who never learned about that stuff. Actually the Icelandic textbooks I had at the time kept mentioning “but you already know this from Swedish!” so maybe I should have looked up Swedish grammar.

Personally I’m much more comfortable talking with other learners than native speakers in Icelandic, so if you can find some (I’ll practice with you, I’m also bad at everyday conversation!) that might be easier. Old Icelanders are fine too, they tend to be happy to talk to foreigners (one described it like “Iceland was dead boring before you foreigners came along, foreigners are the best thing to happen to Iceland”) and also speak a lot more clearly than young people. I think non-natives tend to be a lot more understanding towards mistakes and can also explain things better (depending on their native language at least). It’s just really scary to talk to a native speaker who is probably sitting there thinking that you speak/write terribly and then maybe they don’t even realize how difficult their language is to an outsider.

With Swedish, I’m not very serious about learning it (I just have to, because I need to move there) and I don’t care who I talk to or if I talk so badly no one can understand me, so there’s really a huge difference even just in the rate that I improve with Swedish and with Icelandic because I’m not afraid to talk in Swedish. Or maybe that’s also because Swedish is just easier. I’ve noticed that a lot of people that can brazenly talk to anyone with their bad language skills don’t seem to even worry about themselves being bad, and don’t tend to be super serious about becoming fluent either, so I guess it’s just that kind of mentality. When I was in grade-school I never thought you could actually be fluent in another language (unless you actually moved to the country and lived there for like ten years), considering I’d spent years studying Spanish in school and still couldn’t understand a word from a native speaker, so you can imagine just how much I didn’t care if I was bad in Spanish.

That all being said, I think English slang is really funny sometimes, especially if it’s said really incorrectly or by someone you wouldn’t expect to use it… Once I had an old man who just burst out with a completely native-sounding “We’ll cross that bridge when we come to it!” despite having a strong Icelandic accent in everything else.

Alex:

I’m also turning into a bit of a Nordicphile after Icelandic. We’ve had tons of Danish TV and although it took a fantastic amount of time to get used to the sound of the language, I’m beginning to like it.

I think my first year was spent trying to figure out what cases were and how you used them. As soon as you’d grasp the logic of them and associate them with meaning, then you start to see all the lexical case (i.e. arbitrary), like sakna with the genitive, haetta with dative and so on.

I was in a situation of not having spoken Icelandic before and being in a houseparty with about 20 of them last July, and it was awful. I just listened for the most of it, and when I did try it was funny because they were saying things like “He bends the words really well!”, where obviously they were translating beygja as ‘bend’ rather than ‘decline’, which I thought was funny.

I’ve got a friend who’s always translating Icelandic slang into English as a joke and he knows it doesn’t make any sense to me, but it’s quite funny. I learn a lot. Last week he was telling me about the clothesline slang. So, if you’re drunk or have been drinking for a long time you’re described as “blautur” (wet), and if you haven’t had a drink in a while then you’re “þurr” (dry). So, on Fridays people are always saying “I’ve been on the clothesline all week (“drying”=not drinking)” or “I’m coming off the clothesline tonight!” which I thought was pretty funny.

Another one was, when you’re not understanding something to say the equivalent of “I was like a fish on land when you were talking about that.” – I guess we have “fish out of water” for when you’re in an uncomfortable situation so it’s sort of related.

sequoia:

@Alex I don’t want to fill the comments section with a long discussion that also might go too off-topic, so if you’d like we can move this to Email – I already sent you a test Email, it’ll have “sequoia” in the Email address and might show up in your spam box. So if you’d like you can reply to that and we can keep talking, I like being able to have conversations about this kind of thing. : D

Eric Swanson:

@ Sequoia – Hi, Swedish is my second language and I live about half the year in Sweden. I was wondering if you could share the name of the Swedish Icelandic text you use. I have found that learning Icelandic has really helped me understand a lot of things about Swedish. For example we say “till havs” “till bords” but I didn’t know why or read about it anywhere in a Swedish textbook, as I recall. But when I studied Icelandic I understood why we say a lot of things in Swedish.

sequoia:

@Eric Swanson Hi, sorry, I stopped getting Email alerts for comments for some reason so I didn’t see this until now.

I use “Sænsk málfræði” by Sigrún Helgadóttir Hallbeck, from 1991. It has a yellow and blue cover and it’s actually not very thick. I’m not sure where you can buy it anymore because I just keep checking it out from the library and make notes from it, but considering the library has three copies you should be able to find it somewhere. I personally think it’s really valuable so hopefully you get some use out of it!