Noun Genders and A-mutation Posted by sequoia on Apr 17, 2012 in Icelandic grammar

I haven’t taught anything in a while, so today we have “genders of nouns”. Again this is taken partially from the textbook I’m writing. It’s very important to know the gender of nouns because how you change other parts of the sentence (like adjectives, which also have genders) depends on what gender the noun is.

Nouns have one of three “genders”. The three genders are masculine, feminine, and neuter. This has nothing to do with the meaning of the word, for example “dress” could be a masculine word while “beard” could be feminine or neuter. “Gender” is only a term used to categorize how the word conjugates.

“Conjugate” means the same thing as “decline”, except the word conjugate is only used for verbs and decline is used for everything else. (Nordic people might also know this as “bend” or “bending”.) You’ll probably often see these two words in textbooks for Icelandic. What they mean is simply that the word changes – like how we have “run, runs, running, ran”. That would be some of the conjugations (forms) of the verb “run”. Cats and cat are declinations (forms) of the noun “cat”, but as you can see it’s basically the same thing.

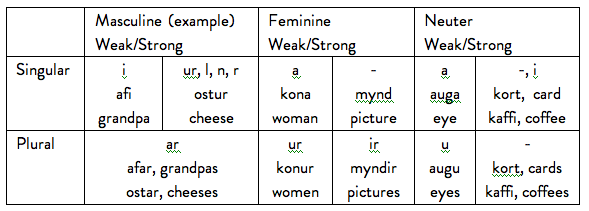

Each type of noun changes in different patterns when changing from singular to plural, or between cases (which will likely be covered in later posts). That is, if they’re not “irregular” and do follow a pattern. In addition to genders, there’s also a distinction between “weak” and “strong” nouns and while still being the same gender (ex. “weak masculine” and “strong masculine”), they further change in different patterns. Strength is simply another categorization, like gender. It doesn’t matter much in nominative, but it helps to know them for the other cases.

To make plural nouns (ex: cats) you need to find the “stems” of words. In that example, “cat” would be the stem because it is the piece of the word that doesn’t change. In general, you can take off these letters if they’re at the end of a word to find the stem: ur, r, a, i. You take off the second consonant when there are double consonants (like steinn – stone, the last n would be taken off to get the stem). Then you add the new ending for that gender and number, to get the case or plural.

Some words are already stems ( “epli – apple”, “haf – sea, ocean”, “höll – palace”, “mynd – picture”) and in that case you wouldn’t remove any letters. In this chart first the letter(s) that is the ending is listed, then an example word, and below is what you would change that ending to in order to make the plural.

Here is the chart for the dictionary (nominative) case, the one you will learn first:

Note: You’ll notice that “neuter strong” words are the same in singular and plural. How do you know when it means what? It’s just the same as in English – you can’t say you have “sheeps”, “a specie (as in species)”, or “offsprings” either.

For example:

Bær (town), sala (sale), steinn (stone), spurning (question).

The stems are: bæ, sal, stein, spurning*.

Then you tack on the new endings:

Bæir (towns), sölur* (sales), steinar (stones), spurningar (questions).

*See below for -ing endings and see the “a-mutation” section for why sala changes to sölur.

You’ll notice that it’s possible for a both a masculine word (afi – “grandpa”, sopi – “sip, mouthful”) and a neuter word (kaffi – “coffee”, epli – “apple”) to end in “i”. The same can happen with nouns that end in “a” for feminine (síða – side) and neuter (milta – spleen).

Often neuter words ending in “a” are body parts, neuter words ending in “i” are loanwords (but all words that begin with “p” are loanwords – so says one of my teachers), and often items and concepts (like “car, boat”, and “time, sound”) are masculine or neuter. There is actually no precise pattern or rule, and so there is no definite way to tell the gender of a word just by looking at it alone in dictionary form. Sometimes this is even just because the word was spelled differently in older Icelandic and then they changed the spelling.

Exceptions:

1.) When a noun ends in –ing (æfing – training, practice, drill) it is feminine and becomes plural by adding –ar (æfingar – drills).

Tilfinning – sensation, sentiment, feeling

Eining – solidarity, harmony, unit

Blæðing – bleeding

2.) Some masculine words end in “ir” in plural instead of “ar”.

Hvalur (whale) – hvalir (whales)

Vinur (friend) – vinir (friends)

3.) Other irregulars:

Masculine: Maður (human, man) – menn (men)

Masculine: Skór (shoe) – skór (shoes)

Masculine: Herra – “mister, lord”

Feminine: Miðstöð (center) – miðstöðvar (centers)

A-víxl / A-mutation:

Notice how the “a” in “sala” changes to “ö” in “sölur”? This is due to a rule called the “a-mutation”, or “a-víxl” (víxl – alternation) in Icelandic. I mentioned this in a previous post. This affects all word types in Icelandic, not just nouns. There are three rules for this:

1.) If the ending of the word contains u.

Saga (story) – sögur (stories)

Sala (sale) – sölur (sales)

Taska (bag) – töskur (bags)

Ég tala (I talk) – við tölum (we talk)

2.) If the word is just a stem with no ending, and changes (this can work backwards too).

Barn (child) – börn (children)

Blað (page) – blöð (pages)

Höfn (harbor) – hafnir (harbors)

Tjörn (pond) – tjarnir (ponds)

3.) If “a” is the second vowel in the stem, it changes to “u” instead of “ö”. This is because the vowel is unstressed. In Icelandic the stressed syllable is always the first syllable in a word, unless it is a compound word, but we’ll cover that in a later post. I only have one example because all the other ones I can remember/find aren’t nouns or aren’t in nominative case.

Eitt hundrað (one hundred) – tvö hundruð (two hundred). “Hundred” changes to plural because there are “two hundreds” in “two hundred”.

Exceptions:

1.) Hattur. This is because in Old Icelandic it was “hattr”. The –ur is a relatively recent change.

2.) If the first vowel in a stem is “a” but the second vowel isn’t, the rule doesn’t apply:

Agúrka (cucumber) – agúrkur (cucumbers)

3.) Only “a” will change, “á” will not:

Sála (soul) – sálur (souls)

4.) “Au” will not change. This is because it’s a “dipthong”, which basically means that it’s a “special vowel pair” and is treated kind of like a single letter in some regards. Remember the spelling rule for au? That is also because it’s a dipthong. If this is hard to imagine, look at how in English ae was sometimes spelled æ and oe was œ (you’ll mostly notice this when reading classics), they had their own characters in the alphabet.

auga (eye) – augu (eyes)

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

About the Author: sequoia

I try to write about two-thirds of the blog topics on cultural aspects and one-third on the language, because there's much more out there already on the language compared to daily life information. I try to stay away from touristy things because there's more of that out there than anything else on Iceland, and I feel like talking about that stuff gives you the wrong impression of Iceland.

Comments:

Veronika:

Very helpful. Looking forward to your explanation of cases.

sequoia:

@Veronika I’m really glad it helped, I don’t know the Icelandic level of most of the readers so I’m always unsure if everyone already knows what I’m writing about. Also, thank you for always commenting, it makes me really happy to know that I have a regular reader!

I have a post on genitive case already written, but it isn’t everything about the case (it’s only about making compound words). That will be posted on May 5th. : D

Eric Swanson:

I really enjoy the charts and I’m copying them down. You are doing a great job explaining the structure of Icelandic to me. I find it interesting that words that end in “ing” in Swedish always decline to their plural by adding “ar”, just as in Icelandic. My other impression is: Icelandic has lots of rules and exceptions to those rules. But I’ve learned enough Icelandic now to read and correspond using iGoogle. Cheers!

sequoia:

@Eric Swanson Sorry, for some reason the site has stopped giving me Email alerts for comments so I didn’t see your comment until now.

If you have anything you want me to talk about, explain, etc. just ask! I really enjoy learning Icelandic myself so even if it’s some strange grammar rule I’ve never heard of, I’ll have a lot of fun just looking it up for myself. I also want to write a really easy-to-understand textbook for Icelandic for people who’ve never learned a foreign language before, so if you ever find something in my explanations that are unclear please tell me so I can try to fix them. I think it’s really easy to get daunted by all the grammar terms and the poor explanations in most textbooks and online, along with the difficulty of the actual language… I think most people learning Icelandic actually seem to be linguists and many are more interested in Old Norse too, so a lot of textbooks reflect that.

I’m starting to learn Swedish myself and I’m really surprised at how similar some things are. I’ve never learned languages that were similar before (I’ve only ever studied Spanish, Japanese, and Icelandic, plus my first language is English – not very related at all!) so it’s really nice! Although it would be nicer if there were clearer rules for telling noun genders in Swedish like there are in Icelandic, I found out some things about that from taking a look at older Swedish. Actually the Swedish Transparent Language blog is something I browse on occasion and I have a lot of fun reading, although some of their old entries are kind of dubious (I don’t think I need a single entry only on hardbread when I already know what hardbread is haha).