Compound Words and Genitive Case Posted by sequoia on May 5, 2012 in Icelandic grammar

Genitive is one of the most-used cases in Icelandic. Not only is it used to show possession, but it’s also used when making compound words. Compound words are really confusing when you don’t know enough vocabulary to tell where to break the word up in order to look up all the parts in the dictionary. Compound words are really, really common in Icelandic.

You will probably be taught first nominative case, then accusative in other places. This is just because it’s the order everyone remembers them in and is taught them. I don’t think it’s necessary or even particularly good to learn them in that order, but after you know all four you’re going to want to keep them in the “standard” order in your head. This is so that if you see grammar charts elsewhere or go to an Icelandic class you don’t mix things up because of your mental order. This paragraph may sound confusing but I’ll make clear what I mean if I end up posting about all the other cases too.

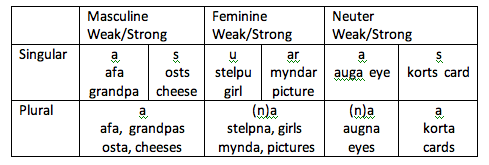

Remember the words from the noun gender post? These are them in genitive:

“Kort” in nominative singular is also “kort” in nominative plural, but in genitive singular it’s “korts” and in genitive plural it’s “korta”. Basically genitive case is one of the cases we still kind of have in English, so it’s a lot easier to understand than any of the other cases. Often it’s used to show possession, so in English, for korts/korta the “s” stem would be ‘s (card’s, dog’s) and the “a” stem would be s’ (cards’, dogs’). Messing up genitive case can be the equivalent of saying “I grabbed the dogses’ bone”. As for “stelpa – stelpna” and “auga – augna” gaining an n, these follow an “n-insertion” grammar rule that I may talk about in a later post.

Although there are some different ways to show possession in Icelandic and genitive case is one of them, this post here is only about compound words and not about the possessive side of the case or when otherwise to use it (meaning, genitive doesn’t always mean possession). I’m teaching this because it was something I wondered about for a long time and it wasn’t in any of my English textbooks, but every textbook will teach you about the possession part.

A compound word (a word made up of two or more other words, like “firefighter”) can be made by putting the beginning words into genitive case and leaving the last word of the compound in singular, nominative/dictionary case. (It’s called dictionary case because if you look up a word in the dictionary, that’s the case it’ll be in on the entry.) The gender of the resulting compound word is the same gender as that last word. Often the genitive part is in genitive plural, but some are in genitive singular, such as words including “Ísland – Iceland” because Ísland has no plural form.

Ex. “ostur (nominative singular)” from above is “osta” in genitive plural. “Hús – house” is in nominative. Adding them together makes “ostahús – cheese house”. The resulting compound word is neuter gender, just like hús is, and to decline the word you would use the same pattern as for hús and leave “osta” alone, unless some other grammar rules interfere.

“tölvupóstur – email” is made up of “tölva – computer” (which looks like “tölvu” in plural genitive) and “póstur – mail/post (nominative singular)”. It’s masculine gender because “póstur” is masculine.

“bókabúð – bookshop” is “bók (bóka in plural genitive)” and “búð – shop”.

“barnabók – children’s book” is “barn (barna in plural genitive)” and “bók – book”.

“barnabókabúð” would be “children’s bookshop”. The first two words are both in genitive plural but the last is in nominative singular.

One exception is verslunarstjóri, made of “verslun – store (in singular genitive form)” and “stjóri – boss (in singular nominative form)”, to mean “store manager”. This makes sense if you realize that he’s probably only the manager of a single store, but I don’t know the actual rules for when words should be in singular or plural genitive – all I have is a small list of exceptions and no explanation. I’ll research it and edit this post if I ever find anything, so if anyone knows for sure please comment.

Some compound words are really funny if you look up each part of the word separately. Usually these types will be searchable in the dictionary regularly (so you can look up “fireman” as one word and not “fire” and “man” separately).

Viðskiptavinur, customer – “viðskipta – business/business transaction” and “vinur – friend”.

Viskustykki, tea towel – “viska – wisdom” and “stykki – piece”.

Orðabók, dictionary – “orð – word” and “bók – book”.

Some words have bits that were made up when they created the word, sometimes in the sense that they are parts of a pre-existing word (maybe for example, the word in a case other than nominative) that then get added to another word to make a new word with a new meaning. You can further make compound words with the newly-made word. This means that even if you can break a compound word into parts, sometimes one part isn’t actually a word. This isn’t the best example, especially since I don’t know much about these things myself, but look at “auglýsingastofa – advertising agency”. Here are similar-looking words that come up if you try to break it down further and further:

stofa – room

auglýsing – advertisement

að auglýsa – to advertise

auga – eye. (“aug” doesn’t mean anything on its own)

lýsing – description, lighting

lýsa (feminine noun) – whiting (some type of fish)

að lýsa (verb) – to light, expose, describe

lýsi (masculine noun) – fish liver oil.

What is “auglýsing” actually derived from? I have no idea because I don’t have an etymology dictionary, but if you didn’t know to look up “auglýsingastofa” in the dictionary all at once instead of “auglýsinga stofa” or “aug lýsinga stofa”, you’d probably be very confused as not even “advertising room” would make sense in context. In the future I’ll post more about this, but the general idea is that even though it may be a compound word or at least look like one, it might have some parts that you just can’t break down.

“Netfang”, which is another word for Email, is “net – net/network/internet” and “fang”, also used in “heimilisfang – address”, “póstfang – postal address”, and “veffang – web address“. “Fang” on its own means “outstretched arms/provisions” so it doesn’t make sense if you look things up separately here either. Also, none of these compound words have the first word in genitive – this will be explained in a later post, as there are multiple ways to make a compound word.

Here’s part of a long “word” I took from here, “útidyralyklakippuhringur”. All words changed to nominative case:

úti – outside

dyr – door

útidyr – front door

lykill – key

dyralykill – door-key (the key to the door)

kippa – bundle/sheaf

lyklakippa – keyring/bunch of keys (“lykill” changes from kil to -kla at the end because of a certain “assimilation” grammar rule)

hringur – ring/circle (seems to be redundant in the word keyring as to my eyes it looks like “keyring-ring” or maybe it’s supposed to be “ring of keyrings”, but some people use it to mean just keyring)

You could of course also write the equivalent of something like “the ring of keys to the front door” instead of “the front-door keyring”. In some cases that seems to be preferred. While I’ve seen a lot of two or three-word compounds I haven’t seen many of them four and up, even though it’s perfectly possible to just keep putting words together. If you can read the Icelandic, more detailed rules and examples are here for deciding on if you should write it as a compound word or not, and there are plenty of Icelandic grammar books that at least broach the subject although I don’t know about what’s available online. I might also write a post on this in the future.

I mentioned a difference in stress placement in compound words in a previous post. If a compound word is only made up of two words, then the spoken stress is on the first syllable of the first word but is usually unheard (or only very lightly heard) on the second. If it’s made of three words, then a clear stress is heard on both the first syllable of the first word (“barnabókabúð”) and the first syllable of the third word (“barnabókabúð“). I have no Icelandic friends who can record audio, so I can’t have them say examples for you, but maybe you’ll notice this yourself when listening to spoken Icelandic. If you don’t get what I mean by stress, think of how “convict (prisoner)” and “convict (declare someone guilty of a crime)” have two totally different meanings based on where the spoken “stress” is placed.

In her Icelandic courses my wife was told that if you have no idea what case a word should be in, never guess genitive. This is in part because genitive on its own can change the meaning of words to be possessive, but the other part is that people expect you to be better at knowing which case to put a word in if you know cases at all. If someone is using only nominative case then you can easily get used to it, (“I go work yesterday”) but if someone is using the completely wrong case at random times it might be a bit harder (“mine go work yesterday’s”).

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

About the Author: sequoia

I try to write about two-thirds of the blog topics on cultural aspects and one-third on the language, because there's much more out there already on the language compared to daily life information. I try to stay away from touristy things because there's more of that out there than anything else on Iceland, and I feel like talking about that stuff gives you the wrong impression of Iceland.

Comments:

Eric Swanson:

Thanks for this article about the genative case. Besides being informative about Icelandic it is also informative about Swedish because we still have some vestages of the more complicated Icelandic genative case. We usually just add s but sometimes we change a vowel ending in a compound word. For example, a street vendor selling hot dogs would call his mobile kitchen a “gatukØk”.

sequoia:

@Eric Swanson Sorry, the site’s stopped giving me Email alerts for comments so I didn’t know your comment existed until I checked manually just now.

Yes, I’m starting to learn Swedish myself (and my wife is Swedish) and I think it’s kind of funny which things were kept and which changed, especially because I’m using an Icelandic textbook to learn it so they have all kinds of funny notes about things. Although I think it’s still far better than using an English textbook to learn. If it were my choice, I’d be a lover of Swedish and not Icelandic because the grammar is a lot easier, and you can even get videogames in Swedish!

I also really like Faroese and one of the four cases is dying out (or is dead?) in that, although I don’t know much about it because I’d rather become really good in Icelandic and Swedish before I start to work on Faroese. If I start to research too much then I lose focus and stop studying Icelandic and only focus on Faroese, for example…

I’ll tell you something funny that you might not know – in our Icelandic classes and a few Icelandic textbooks (in Icelandic) as well, when they mean that a word is just a stem with no ending they add -ø. So it looks like “hest-ur” (nominative) but “hest-ø” (accusative) or “barn-ø”. Well, maybe it’s not funny to everyone, but you can’t even type ø on an Icelandic keyboard (at least, not on mine!) so why not think up an easier symbol to write?

Ragnheiður:

One point about viskustykki/viskastykki, its first part is really danish viske.

Dom:

Really interesting read, thanks for all the examples which were very useful

Although for viskustykki, I think you have the wrong analysis. There is a (rare?) verb “viska” meaning “to wipe” – I think this would make more sense than wisdom in the context of teatowels!