Is your neighbour an elf? Posted by hulda on Jun 22, 2012 in Icelandic culture, Icelandic customs, Icelandic grammar

Happy Midsummer/Solstice everyone! Unlike many European countries, this time of the year is not celebrated very much in Iceland, at least in comparison. There’s Þórláksmessa (the summer version of it – one is held on 20th June and another on 23rd December) held in the memory of Þórlák hinn helga Þórláksson, the patron saint of Iceland, and some years ago a group of artists began to hold a Jónsvaka where lots of new artists get a chance of showcasing their work, but there are no midsummer poles, no bonfires and no big drinking festival*.

Happy Midsummer/Solstice everyone! Unlike many European countries, this time of the year is not celebrated very much in Iceland, at least in comparison. There’s Þórláksmessa (the summer version of it – one is held on 20th June and another on 23rd December) held in the memory of Þórlák hinn helga Þórláksson, the patron saint of Iceland, and some years ago a group of artists began to hold a Jónsvaka where lots of new artists get a chance of showcasing their work, but there are no midsummer poles, no bonfires and no big drinking festival*.

However, I’m more used to celebrating the Midsummer with a little touch of supernatural (in my homecountry this is the time of the year when people attempt to see the future or try to find lost treasures by magic). For us it’s unusual, so I thought that writing about the exact opposite – the commonness of the supernatural – would be a good topic for today.

A poll done not so long ago found out that while Icelanders generally don’t believe in f.ex. elves (álfur/álfar) they’re still very reluctant to state that elves and hidden people (huldufólk) would not exist at all. Considering how much the hidden world is a part of everyday life this is perhaps not as surprising as it might at first seem like. There are any number of areas called elf-something like Álfabakki (= Elf Strand), a road that goes fairly near to where I live and probably just as many if not more folk tales of elves of these areas.

However, old folk tales is not all there is. There’s also a good amount of newer stories of elves and hidden folk and people coming across them, usually because humans are trying to build something over a place where the others live. This tends to go badly for humans. Machines cease to work, freak accidents and even deaths happen at the site and sometimes this brings the whole project to a halt.

The next step is often to make sure that it really is the hidden who are responsible. This is done by inviting a medium over to look at the site and possibly attempt to have talks with the original residents. I’m not trying to pull your leg or anything, this is exactly how it’s done and in all seriousness too. I suppose when people are in clear yet mysterious danger they get ready to believe in anything that might be the cause.

The medium then tries to come to a some kind of a deal with the hidden. First of all the medium finds out if there’s any way of continuing the project. Can the elves move house? How much time will they need for that? Or if that’s not a possibility, how about humans help them move their house instead? As elves are believed to live in rocks this would mean that an elf rock will be identified and very carefully moved out of the way. A third option is to cease the work and to bring it back on the drawing board. It’s not unusual that whole roads have been forced to go around an area where the elves live.

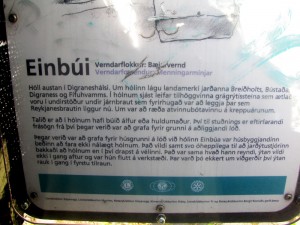

Einbúi is one such site. There’s a sign board there with an explanation on why the place is special:

The first chapter describes how here used to be a landmark of the areas called Breiðholt, Bústaður, Digranes and Fífuhvammur and that the rocks here were originally meant for a railway that would have been built where there now is Reykjanesbraut, Reykjanes Road. Then it gets to the elves:

“Talinn er að í hólnum hafi búið álfur eða huldumaður… …Þegar verið var að grafa fyrir húsgrunni á lóð við hólinn Einbúa var húsbyggjandinn beðinn að fara ekki nálægt hólnum. Það vildi samt svo óheppnilega til að jarðýtustjórinn bakkaði að hólnum en í því drapst á vélinni. Það var sama hvað hann reyndi, ýtan vildi ekki í gang aftur or var hún flutt á verkstæði. Þar var þó ekkert um viðgerðir því ýtan rauk í gang í fyrstu tilraun.”

“It’s said that an elf or a hidden person had been living inside the hill… …When they began to dig for the foundations of a house next to the hill Einbúi**, the constructor was warned against going too near to the hill. Unluckily a workman backed a bulldozer into the hill and the machine died on the spot. It didn’t matter what he tried, the bulldozer would not start again and it was therefore sent to a repairs shop. No reparations were done on it, though, because once there it started on the first try.”

*The drinking habits of Icelanders considered this is probably a lucky thing.

**Einbúi is nefnifall***, nominative case. It’s the preposition við that here demands another case, either þólfall (accusative) or þagufall (dative), depending. Þólfall is more common with preposition við, and even though Einbúi has the exact same form (Einbúa) in both þólfall and þagufall, the word hólinn (nefnifall: hóll) that goes before it shows that þólfall indeed is what’s used here. An easy rule is that if við is used to state location, as in that X is near Z, it’s followed by þólfall.

***I’d much rather use the Icelandic word for the cases to avoid confusing those people whose languages have accusative and dative cases that work differently. I’ve found that at least for me it’s easier to use the Icelandic versions instead of trying to go by the exact terms of what f.ex. an accusative is – in Icelandic you can’t always use an accusative in every situation that would otherwise call for it.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

About the Author: hulda

Hi, I'm Hulda, originally Finnish but now living in the suburbs of Reykjavík. I'm here to help you in any way I can if you're considering learning Icelandic. Nice to meet you!

Comments:

Clara:

I’ve got to admit I love reading about this part of Icelandic culture. People over here seem to have forgotten superstition ever existed. XD

I wonder about your note on the cases, as a polyglot I’m studying several langs that use dative and accusative cases and I didn’t hear about the cases themselves really working differently as you put it here. Sure they take their different expressions in different langs but it’s the same basic mechanism so to speak. Since I’ve just started on Icelandic like last month I haven’t read everything about the cases yet, but so far I haven’t noticed anything out of the ordinary as far as acc/dat go, do you mind clarifying what you meant? Thanks in advance! Pretty neat blog by the by! 🙂

hulda:

@Clara Glad you liked it, thank you! Indeed, Icelanders have possibly one of the most unusual attitudes towards the supernatural that I know of. 😀

As for the cases working slightly differently in different languages… hmm. Icelandic, like many other Germanic languages, has verbs and prepositions that can only be followed with a certain case. In f.ex. Fenno-Ugric languages verbs have no such power (and prepositions are nonexistent as suffixes are used instead), the case is always chosen by the meaning of the case and case only. Any verb can therefore be followed by any case.

A thinking pattern that’s based on what meaning accusative or dative cases hold on their own can make studying unnecessarily complicated when it comes to languages that work on an entirely different set of rules. I eventually opted for using the Icelandic case names instead of accusative and dative because I felt they were less misleading for my situation. 🙂

Mrs.Elve:

I completely agree with the paragraph about the cursed hill!!

Can’t wait for yule,

Mrs.Elve