Fighting, viking-women style! Posted by hulda on Nov 20, 2014 in Icelandic culture, Icelandic history

Medieval Norse women tend to make people think of either of two things first: either a stoic-looking linen-clad lady who does nothing besides carrying horns of mead and popping out heroic babies, or a shield-maiden in a skimpy armour. Both images are wrong, but because they answer to two romantic ideals it’s easy to see why they’re as popular as they are.

An Icelandic noblewoman was by no means helpless, yet she was not usually a warrior type either. Going to a battle was not something that was a source of honour for women, which is why you’ll always see a fighting woman have some other motive behind her actions. She may be forced to fight, her husband may be in danger, she’s blinded by anger and gets a chance, these are three reasons I can easily think of off the top of my head for those rare few women that take up arms (on one occasion a whole ship – one lady decided to avenge an earlier attack on herself by sailing her ship onto the attackers’ one, capsizing it).

These cases were treated as unusual. Typically women used what actually was considered a source of honour for Norse women: their wits, strategic thinking, clever manipulation and a technique that is usually referred to as whetting, a way of talking one’s male family members into fighting mood. It was often used in situations where the men seemed none too eager to break an armistice for the sake of revenge.

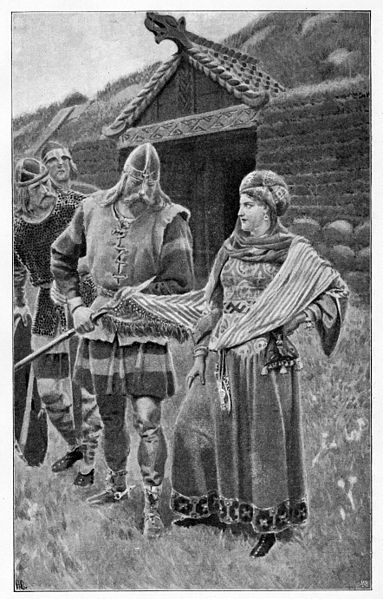

Guðrún smiled at Halldor by Andreas Bloch. Halldor has just murdered Guðrún’s husband and is wiping the murder weapon on her clothes, but she merely smiles back at him, already knowing how she’ll avenge her husband. Picture from Wikimedia Commons.

Because of our modern view whetting is often seen as a sign of evilness, yet back in the day it was actually a way of preserving family honour. It was only done to encourage the men to avenge the death of a family member which, if left unavenged, would tarnish the whole family’s name. It did not matter whether someone’s death was avenged right away or many years after but it still had to be done at some point while people still remembered the case. A whole family could sink in society if they let a member of theirs be killed without retaliation, the men who decided to follow certain noblemen might begin to change sides if they felt theirs was the weaker one, not to mention that a family that was seen as unable to defend itself was an easy target for attacks. A woman who failed her part in these matters risked losing far more than just her own face.

So was that all they did – hid behind their male relatives’ backs, nagging all the while? Far from it. A noblewoman could also command her own warriors as Hallgerður and Bergþóra did in Njáll’s saga, where a disagreement eventually spiraled into an endless vendetta. Both women sent their slaves, servants and allies to attack the other’s side in turn, causing one of the lengthiest and bloodiest family wars of the sagas. This was also no doubt the way women defended their homestead while the husbands were away.

This of course relied a lot on what type of people were left in the house with the womenfolk: in Grettis saga the attackers outnumbered the house-carls, and what even worse, arrived with the precise idea of attacking the ladies of the house. It was therefore only due to Grettir’s quick thinking that the attack was thwarted. Though the Medieval noblewoman might not be helpless she was not always safe from harm either, which brings me to the next point, the myth that “Medieval Norsemen/vikings never harmed women”. They did, sometimes even targeting women as in the above example, but fact is that attacking a free woman was both illegal and not seen as a honourable thing to do. Likewise most warriors would always avoid killing children, because harming one did two things: it set the whole family after your life and gave you a reputation as a coward… but children still did occasionally die during battles.

What about the shieldmaidens then? Alas, they’re largely a myth, possibly based on valkyries. In Iceland it was even illegal for a woman to carry a sword. They could own swords of course, swords were powerful status symbols that could be kept for one’s own children or be given away as priceless gifts, but to use one was strictly forbidden. There are a few exceptions in the sagas but nowhere near enough to make shieldmaidens a thing – if anything, a female warrior was such a rare occurrence (though most likely a few did exist) that she was most definitely written about, therefore perhaps making shieldmaidens seem more common than they actually were. Gesta Danorum (link) may not always be a reliable historical source…

But what about women who actually did fight? Let’s look at these unusual ladies in the next post!

By the way, the article circling around the internet about grave finds supposedly proving the existence of female warriors is a hoax. Sadly, because it would be pretty awesome if it was true! The material it’s based on does not say anything about warriors though, just settlers, and though you might find a sword in someone’s grave it does not mean the person ever used said sword, merely that they owned it. Deciding that a female with a sword was a warrior is just the other side of the coin of modern ideas colouring the past, where the other side is to mark every single sword-grave as a male one.

Other posts in this series:

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

About the Author: hulda

Hi, I'm Hulda, originally Finnish but now living in the suburbs of Reykjavík. I'm here to help you in any way I can if you're considering learning Icelandic. Nice to meet you!