The Ingredients for Mulled Wine in Irish (comhábhair scailtín fíona i nGaeilge) Posted by róislín on Nov 30, 2018 in Irish Language

(le Róislín)

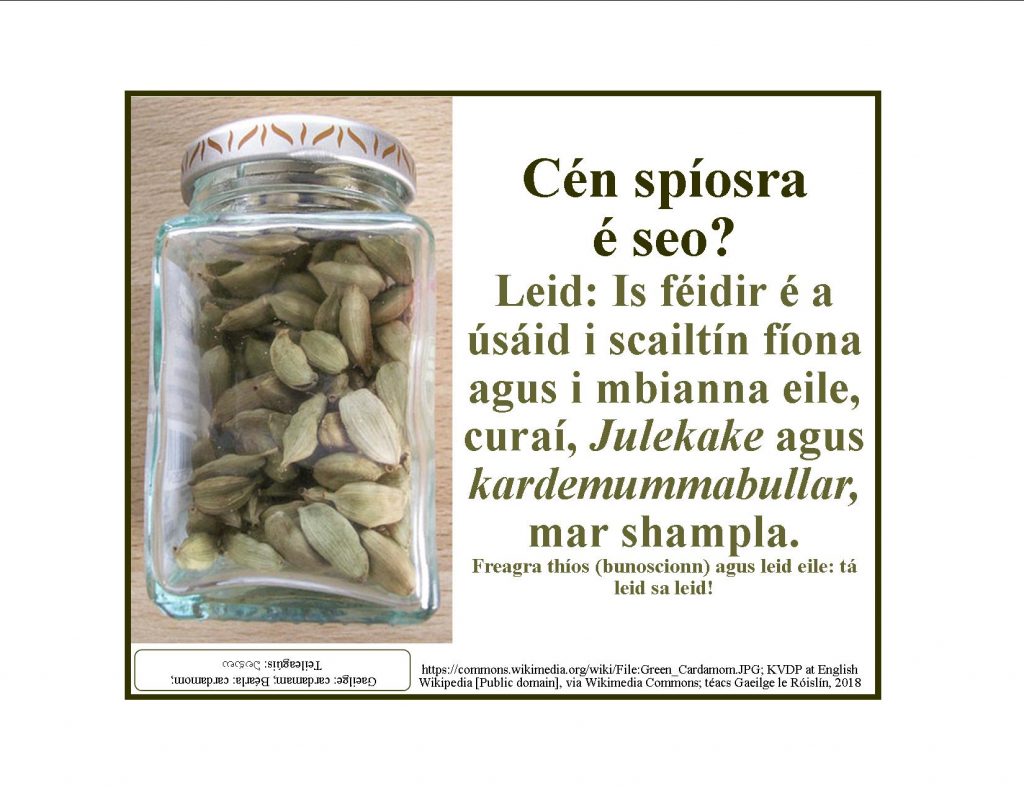

“Scailtín fíona” (mulled wine) is a phrase we introduced in the most recent blog post (nasc thíos). So what exactly are the typical ingredients for “mulled” wine, and why is it called “mulled” anyway?Here are six of the gnáthphríomhchomhábhair (ordinary primary ingredients — sorry for the sesquipedalianism of the word, well, not really sorry — I love it!). Can you figure out what they are? Freagraí thíos.

slisíní oráiste

maide cainéil

faighneoga cardamaim

síolta réalt-ainíse

clóibh

and the one ingredient you can’t see: siúcra (nó mil nó sioróip mhailpe).

Oh, and of course, fíon (wine), perhaps “pórtfhíon” (port wine).

Na freagraí:

slisíní oráiste, orange slices. The word “slice” is actually quite fascinating in Irish, since there are at least five more possibilities including slis, slisne, sceall, píosa, and stiall. But further discussion of these will have to wait to be ábhar blag eile (the subject for another blog)

maide cainéil, a stick of cinnamon, from cainéal, cinnamon. Here, “cainéal” changes to “cainéil,” since we’re really saying “stick of cinnamon.” Actually, the Irish for the noun “stick” is actually quite interesting also, since there are at least four more possibilities (bata, cipín, craobhóg, géagán), not including a few phrases which include “a stick” in English but not in Irish (like “camán, a camogie or hurling stick, or “cos” or “géag” for a stick of rhubarb)

faighneoga cardamaim, cardamom pods. A single one would be “faighneog chardamaim.”

síolta réalt-ainíse, star-anise seeds, lit. seeds of star-anise, “réalt-” meaning “star” here

clóibh, cloves (the singular is “clóbh). Note, though, that a “clove of garlic” uses a totally different word, “ionga gairleoige,” with “ionga” normally meaning fingernail, talon, claw, etc. Not that “clove” as a spice is even close to “clove” as a piece of garlic!

siúcra, nó mil nó sioróip mhailpe, sugar, honey, or maple syrup. The basic word for “maple” is “mailp.” It becomes “mailpe” for “of maple” (as in “crann mailpe”) and it becomes “mhailpe” after “syrup” since “sioróip” is a feminine noun. Similarly we have “sioróip sheacláide” and “sioróip chasachta,” both showing the lenition of the second noun (the “s” of “seacláide” changing to “sh” and “c” of “casachta” changing to “ch”)

As for why “mulled wine” is called “mulled wine,” that’s an interesting question. And it’s also interesting that the Irish phrase, “scailtín fíona” isn’t based on a verb that means “to mull,” but rather on a noun that means a hot alcoholic drink. It seems logical to assume that “scailtín” is based on the verb “scalladh” (to scald, scalding, also to burn, injure, sterilize, etc.), but I haven’t actually found verification of this connection. I wouldn’t think that mulled wine would be served “scalding hot,” more like pleasantly warm, but I’m not completely sure. Eolas ag éinne?

The Verb “to mull” – in Irish and in English (re: beverages)

The closest I find in Irish for a verb “to mull” a beverage is the phrase “scailtín a dhéanamh den fhíon.” Literally, that’s “to make a hot drink/scalteen of the wine” (or whatever other beverage is involved, such as “scailtín fuisce“).

As for the culinary term “mull” itself (in English), there are a few theories but nothing definitive, afaik. It may be connected to the Dutch word “mol” (described as a sweet white beer — but what is a “white beer”?) or the Flemish word “molle” (a kind of beer), and certainly these two languages are reasonably close to English, so a borrowing wouldn’t be surprising. Somehow the Dutch “mol” and the Flemish “molle” are supposed to be connected to a Germanic verb meaning “to soften.” Hmm, it does just make me wonder — Irish has “maolaigh,” which can mean “soften” (or flatten, depress, make bald or blunt, become bald or blunt, moderate, modify, etc.). And this verb has pan-Celtic connections (maol also in Scottish Gaelic, meayl in Manx, moel in Welsh, mool in Cornish, moal in Breton — anyone know the Gaulish?). I don’t usually leap to linguistic conclusions but I do wonder if there’s an ancient Continental connection behind all of this, although nothing I’ve read so far gives any hint of a Celtic-Germanic link. Were there Gaulish-speaking Celts in the areas now known as the Netherlands and Belgium? Food for thought, at least to mull over.

There was an interesting article on the verb “to mull” in both of its senses (to think over/ponder and to heat sweetened spiced wine) in the New York Times on 19 May 1996 (nasc thíos). It mostly deals with the first sense, but addresses mulling wine briefly.

And now for the Paul McCartney connection — or, errmm, not really. But “Mull of Kintyre” is a beautiful song, and this Scottish “mull” refers to a bare (rounded, bald, blunt) i.e. treeless rock at the end of the Kintyre peninsula. The actual Gaelic place name is “Maol Chinn Tìre, the same “maol” as we just discussed. Surely a fine place to enjoy some mulled wine, or perhaps, more appropriately, one of the locally-produced Campbeltown single malt whiskies (uisce beatha aon bhraiche). And a discussion of that, and the process of “driogadh” (distilling) could surely be ábhar do bhlag eile arís. And reasonably seasonal, chomh maith. Féiltiúil, ar a laghad. Till then, sláinte agus slán go fóill (go “Skol“?) — Róislín

P.S. As for the other three foods mentioned in the graphic that use cardamom, they are curaí (curry — no surprises there), the Norwegian Julekake (Christmas bread), and the Swedish kardemummabullar (cardamom rolls). Blasta, blasta, blasta!

Naisc

1) ‘Tis the Season for … Festive Drinks (‘Deochanna Féiltiúla’ in Irish) like ‘Mulled Wine’ or ‘Hot Buttered Rum’ Posted by róislín on Nov 23, 2018 in Irish Language

2) https://www.nytimes.com/1996/05/19/magazine/on-language-mulling-over-mull.html

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Leave a comment: