Carsulae e la via Flaminia Posted by Serena on May 6, 2011 in Uncategorized

When I visit an ancient site I like to let my imagination wander and to ‘feel’ the history. I find this much harder, or even impossible to do amongst hoards of tourists, so I prefer to find lesser know places, such as the ruins of the Roman town known as Carsulae near Terni in Umbria.

L’antica città Romana di Carsulae owes its existence to la via Flaminia, the Roman military road which was opened between 220 and 219 a.C. (avanti Cristo, or Before Christ) by Caio Flaminio. This important route, which ran between Roma and Ariminium (the Roman name for Rimini) on the Adriatic coast, was used by Roman troops to move rapidly into territory already conquered and to undertake further expansion of the empire.

Carsulae’s origins go back to the II secolo a.C. (2nd century B.C.) when it began to develop beside the ramo occidentale (western branch) of the via Flaminia due to the movement and aggregation of local communities who benefitted from the progressive Romanizzazione dell’Umbria (Romanization of Umbria). Latin authors record the favorable location of the town on the margins of a fertile pianura (plain). Over the course of time residential villas were built by important people from the capital who came to ‘fare le cure’ (take the cures) at the abundant local acque termali (thermal baths) which can still be found today at nearby Sangemini Terme.

In the IV secolo d.C. (4th century A.D.) Carsulae fell into decline due to the progressive disuse of the western branch of the Flaminia in favor of the more accessible ramo orientale (eastern branch). The final blow to the town’s fortunes came in the form of un sisma (un terremoto – an earthquake) which struck in the second half of the VI secolo d.C. (6th century A.D.)

Well, that’s enough of the history lesson! What made Carsulae special for me? There are some quite impressive ruins to see, such as La Cisterna Antiquarium, l’Anfiteatro, il Teatro, il Foro, and the beautiful Chiesa di San Damiano (3.) which is, basically, a ‘recycled’ Roman building that was transformed into a church around the XI (11th) and XII (12th) centuries d.C. But for me the most evocative element of Carsulae, the thing that transported me back through time, was my walk from the ruins of the town center, and out towards the area of the necropoli (necropolis, or cemetery).

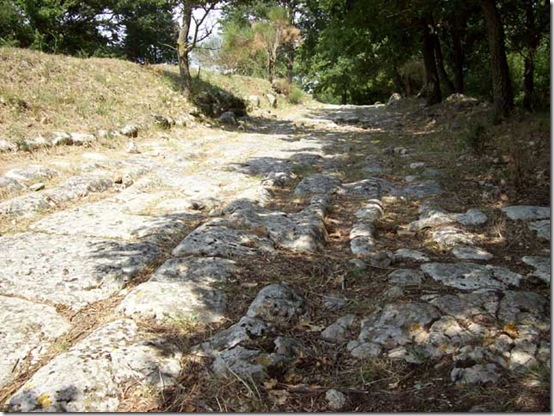

1. The rutted surface of la via Flaminia

Flanked by the ancient remains of the Forum and the Basilica, the massive stone paving slabs lead us up a gentle slope to the brow of a hill. We pass through a shady avenue of cerri (holm oaks 1.) and see before us the remaining central arch of l’Arco di San Damiano (2.) which was once the northern entrance to the town. Just beyond the arch lies an oak wood containing the massive monumental tombs of wealthy and important Carsulae citizens.

2. L’Arco di San Damiano

I feel a need to touch the weathered stone blocks in order to make contact with their memories. How many baking summers and gelid winters have they seen? Tenuous plants push their roots into cracks and lizards scuttle over their sun warmed surfaces. Who were the people whose lives played out in this place, what were their thoughts, hopes, beliefs? I run my fingers over the deeply etched ruts carved by the wheels of thousands of carts and carriages into the limestone paving slabs that lie, as they have done for more than 2,000 years, along the path of the via Flaminia. Quanti piedi (How many feet) … of centurians, contadini (peasants), pastori con le bestie (shepherds with their animals), families rich and poor have followed this road and passed as I have today through l’Arco di San Damiano?

3. A local wedding takes place in la Chiesa di San Damiano.

The guests stand on the slabs of the ancient via Flaminia.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

Phillip:

I too love to feel the history, wonder who walked here, how they lived, what the place looked like, smelled like those many years ago. I also like the way these blog posts teach language. My family is Welsh, Irish and French but I feel a love for Italy its language, history and culture. Thanks for helping me grow my vocabulary.

Lesley Brennan:

Molto interessante, grazie, Serena.

It’s great to explore lesser known antiquities and just be there and imagine the past. Some years ago, I visited the Etruscan tombs at Cerveteri, also off the usual tourist trail – very memorable.

Rini:

Great post. I have an aversion to large crowds of tourists too, which is one of the reasons I love living in Lunigiana so much! Very few tourists here and many many historical ruins to visit. We’re off to Rome in a couple of days, so I’ll be putting up with MANY tourists (but many historical sites!)

Serena:

@Rini Ciao Rini, grazie per il commento. Ho dato un’occhiata al tuo blog, bel lavoro, complimenti. Quest’anno ce ne sono tante di zecche, abbiamo infine dovuto mettere i colari anti parassiti sui nostri gatti perché ne raccoglievano troppe, ed è molto più dificile toglierne una da un animale peloso che non un ragazzino!

Quella bestia che Chris ha in mano in una delle foto si chiama ramarro. Sono molto più visibili in questo periodo e sono solo i maschi che hanno la gola blu. Vedi qua: http://www.naturamediterraneo.com/ramarro/

Vedo anche che siete stati su al passo del Cirone, quindi siete passati più o meno davanti a casa nostra. Non mi ricordo se vi avevo dato il nostro numero di telefono? Perchè non fate un salto da noi uno di questi giorni?

A presto Geoff (il marito di Serena)

Vince:

Salve Serena:

I see you have not gone to the politically correct C.E. (common era) and B.C.E. (before the common era). Good for you.

I also sought out minor ruins when I lived in Italy. In a way, they tell us more in their commonality. I get the same ‘historic’ feelings when I hold Roman coins in my hand from the exact time period I am reading about: be it history or just a historical novel. Think how many people have used a well worn coin. How many transactions?

I love to encounter inscriptions in Latin and try to translate them. Once I even thought I encountered a mistake on a building which had the number: XIIII. However, it turns out that the Romans also wrote ‘4’ this way. (They just never told us that in my Latin class.)

Did you see any grave stone inscriptions in the cemetery? These really hit home. Imagine reading ‘Our Beloved Slave Marcus’.

Great post. Love it when you do history.

Vince