My Father’s War–Part 2 Posted by Serena on Jul 15, 2015 in Italian Language

I recently began writing about my father’s personal experience of the Second World War in North Africa. If you haven’t read part 1 yet you can find here.

Born in Benghazi, Libya, in 1921, my father was drafted into the Italian militia as soon as Italy entered the war in June 1940. Here’s the second part of his tragicomic memoirs, with a translation by Geoff:

Dopo 16 mesi dall’inizio della guerra, ci hanno chiamato nell’esercito, e l’ufficiale incaricato della nostra batteria mi ha messo in fureria (ufficio documentazione militare), e così non sono andato a fare le marce con gli altri. Li vedevo dalla finestra del mio comodo ufficio che marciavano su e giù nel cortile della caserma di El Abiar, a 50 km da Bengasi.

16 months after the start of the war, the army called us up, and the officer in charge of our battery put me into the office of military documentation, hence I didn’t go off marching with the others. I saw them from the comfort of my office window marching up and down in the courtyard of El Abiar barracks, 50 km from Benghazi.

Un giorno che toccava a me di andare a Bengasi a prendere i viveri è arrivata una telefonata dal comando artiglieria di Bengasi di mandare una persona che sapesse usare un po’ le macchine da scrivere per scrivere delle lettere, e così sono rimasto a Bengasi. Il mio capoufficio era il Maggiore Belloni: lui scriveva le lettere a mano e io dovevo riscriverle a macchina. La seconda ritirata è iniziata nel dicembre del 1941 e io ho seguito tutto col comando artiglieria: ci hanno dato a disposizione un camion su cui caricare tutto il materiale da ufficio. Della squadra facevamo parte io, l’autista, il Maggiore Belloni, e il suo attendente Ulderico Colombo, che è ben presto diventato il mio miglior amico.

One day, when it was my turn to go to Benghazi to get the rations, a call came through from Benghazi Artillery Command to send someone over who knew a bit about using a typewriter to write letters, so I ended up staying in Benghazi. The commander of my office was Major Belloni: he wrote letters by hand and I had to rewrite them on the typewriter. The second retreat began in December 1941 and I followed after them with Artillery Command: they put a lorry at our disposition on which to load all the office materials. My team consisted of myself, the driver, Major Belloni, and Ulderico Colombo, his attendant, who soon became my best friend.

La sera quando ci fermavamo io e Ulderico dovevamo scavare il rifugio per il Maggiore: una buca profonda 6 metri! Dopodiché dovevamo scavare il nostro rifugio, ma eravamo troppo stanchi. Allora ho suggerito ad Ulderico di fare una buca profonda solo 2 metri: “Così se cade una bomba lì vicino non veniamo seppelliti dalla terra” gli ho detto. “Bravo, hai ragione” mi ha risposto Ulderico.

When we stopped in the evening, Ulderico and myself had to dig a bunker for the Major: a hole 6 metres deep! After that we had to dig our own bunker, but we were too tired. So I suggested to Ulderico that we make a hole just 2 metres deep: “So that if a bomb lands nearby we won’t get buried by earth” I told him. “Well done, you’re right” replied Ulderico.

Con la seconda ritirata siamo arrivati fino a Tripoli dove ci hanno sistemato nella villa del duca d’Aosta. Sfortunatamente a me e Ulderico ci hanno messi nel garage. Poi gli italiani e i tedeschi hanno riconquistato Bengasi il 29 gennaio 1942 e siamo tornati lì. A Bengasi mi hanno incaricato di andare a prendere gli approvvigionamenti per la mensa ufficiali, perché avevano scoperto che i militari incaricati del servizio ne approfittavano. Alla mensa c’erano 7 ufficiali, e loro davanti al 7 avevano aggiunto un 1, per cui risultavano 17 ufficiali. I viveri extra che avevano rubato li davano a delle famiglie locali in cambio di favori personali con le ragazze.

The second retreat took us as far as Tripoli, where they set us up in the villa of the Duke of Aosta. Unfortunately they put me and Ulderico in the garage! Then the Italians and the Germans retook Benghazi on 29th of January 1942 and we went back there again. In Benghazi they put me in charge of going to get the provisions for the officers mess because they’d discovered that the soldiers who had been given the job were making a profit out of it. There were 7 officers in the mess, and they’d put a 1 in front of the 7 making it 17. They gave the extra provisions that they had stolen to local families in exchange for ‘personal favours’ from the girls.

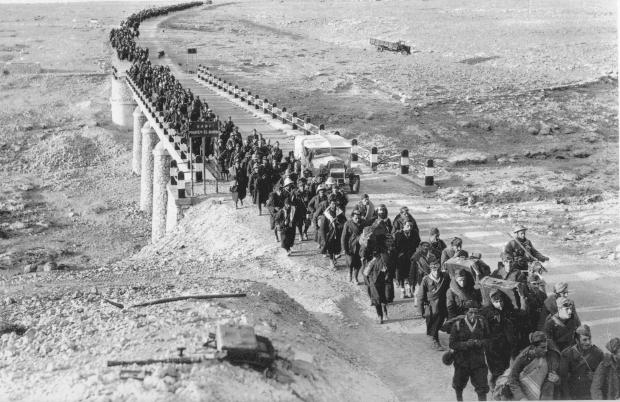

For a brief history (in English) of the the North African Campaign, with many interesting photos, take a look here: WWII – The North African Campaign

… to be continued …

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

paolo:

Molto interessante! Ma ho delle domande riguardo alla grammatica.

“Un giorno che toccava a me di andare a Bengasi a prendere i viveri è arrivata una telefonata dal comando artiglieria di Bengasi di mandare una persona che sapesse usare un po’ le macchine da scrivere per scrivere delle lettere, e così sono rimasto a Bengasi. ”

Perché il congiuntivo viene usato qui?

“Sfortunatamente a me e Ulderico ci hanno messi nel garage.”

Perché “messi” e non “messo”?

E c’è una differenza tra viveri e provvigioni?

grazie…

Serena:

@paolo Salve Paolo, scusami tanto per il ritardo. Una serie di domande molto interessanti, partiamo dalla prima:

‘… di mandare una persona che sapesse usare …’ Perché il congiuntivo viene usato qui?

Allora, ho fatto un po’ di ricerca, ma non ho trovato niente di conclusivo. Ci sono varie possibilità che potrebbero spiegare l’uso del congiuntivo, vediamole:

1) il congiuntivo esprime la soggettività e si usa dopo i verbi di volontà o di comando. Qui non c’è un verbo di comando, ma la volontà, il comando sono sottintesi: “Volevano una persona che sapesse usare …”

2) la frase introdotta dal pronome relativo ‘che’ può avere altre funzioni, in particolare può avere una funzione finale (affinché …), o consecutiva (cosicché ..), o concessiva (se …). Quest’ultimo mi sembra il caso più appropriato: se/a condizione che quella persona sapesse usare la macchina da scrivere.

Seconda domanda: “Sfortunatamente a me e Ulderico ci hanno messi nel garage.” Perché “messi” e non “messo”? Perché il verbo è preceduto dal pronome personale oggetto diretto (ci). E’ lo stesso di quando usiamo i pronomi lo, la, li, le prima del verbo: Ulderico e Nicola li ho messi nel garage.

Terza domanda: c’è una differenza tra viveri e provvigioni? Questo è in parte un mio sbaglio perché scrivevo mentre mio padre raccontava. La parola corretta è ‘approvvigionamenti’, non provvigioni (ho già corretto il testo). Approvvigionamenti è un termine militare più generico di viveri perché comprende tutto ciò di cui l’esercito ha bisogno durante le manovre, quindi anche le armi ecc.

Spero di essere stata chiara

Saluti da Serena

Michele Mandrioli:

English correction.

“Ulderico and myself had to dig a bunker for the Major:” should be “Ulderico and I had to dig a bunker for the Major:”

Reflexive pronouns in English should not be used in place of objective or subjective pronouns. They should only be used to refer back to the subject of the sentence.

This is a very common error in English, often made by well-educated people who should know better. Even President Obama makes this error now and then.

“I did it myself.” “John cut himself while he was shaving.” “You shouldn’t underestimate yourself.”

Geoff:

@Michele Mandrioli Non so se hai notato Michele, ma questo è un blog sulla lingua e la cultura italiana. La gente non viene qui per essere educata sull’uso corretto della lingua inglese.

Inoltre, nel nostro blog mettiamo molta enfasi sulla forma colloquiale, anche se non sempre grammaticamente corretta.

E il blog, ti è piaciuto, sì o no?

paolo:

grazie tanto.

paolo:

E a proposito, l’enfasi sulle forme colloquiali del linguaggio italiano lo rende unico questo blog.