The Italian Monuments Men Posted by Geoff on May 20, 2014 in Uncategorized

Reading about the work of the Monuments Men during WWII left me with a strange sense of unease. It’s not so much the thought of what could have been lost. What really disturbs me is the idea that the same sick brutes who engineered the ‘Final Solution’ could have put so much time, effort and resources into stealing some of the world’s most wonderful works of art. Could these evil psychos actually have been capable of appreciating beautiful painting and sculpture?

William Auge’s recent article ‘Saving Italy’s Artistic Heritage’ got me thinking about the courageous efforts of the Italian Monuments Men, who worked throughout the war risking everything to save Italy’s art treasures. The following is an adapted excerpt from an article on the subject, with my translation.

| –Save the national art heritage! |

Il primo dei ‘Monuments Men’ italiani, Pasquale Rotondi, aveva 31 anni quando l’allora ministro all’Educazione Giuseppe Bottai lo chiamò alla vigilia della guerra per un’impresa da far tremare i polsi anche al più determinato degli Indiana Jones: mettere al sicuro il patrimonio artistico nazionale!

The first of the Italian ‘Monuments Men’, Pasquale Rotondi, was 31 years old when the Minister of Education at the time, Giuseppe Bottai, called him up on the eve of the war with a task which would make even the toughest Indian Jones shake in his boots: Save the national art heritage!

|

| It’s surprising difficult to find photos of Pasquale Rotondi. – |

| –Where to keep the masterpieces? |

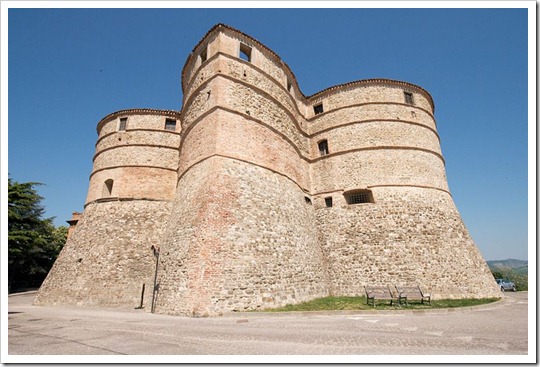

Dove custodire i capolavori? Dopo una lunga ricerca Rotondi individuò la Rocca di Sassocorvaro nelle Marche, risalente al XV secolo. La località sembrava tranquilla. Il professore pensò che quella zona fosse al riparo dal rombo della guerra. C’erano anche grandi stanze asciutte sotterranee e spesse mura fortificate che potevano garantire protezione alle opere in arrivo da tutta Italia.

Where to keep the masterpieces? After an extensive search, Rotondi identified the XV century Rocca di Sassocorvaro in the Marche region. The location seemed out of the way. The professor thought that the area would be far from the rumblings of war. There were also large dry underground rooms and thick fortified walls that could guarantee protection for the works that would arrive there from all over Italy.

| –Masterpieces arrived at the Rocca in absolute secrecy |

Ben presto Rotondi s’accorse che soldi e mezzi non c’erano, tutti destinati allo sforzo bellico. Ma in qualche modo la macchina organizzativa si mosse lo stesso. Capolavori giunsero da tutta Italia alla Rocca nella più assoluta segretezza. Sebbene attorno al castello vi fosse quel continuo viavai di casse di legno in arrivo giorno e notte, nessuno tra spie tedesche e fascisti si insospettì. E il piano riuscì perfettamente.

Rotondi soon realised that the money and equipment weren’t there as they were all being put into the war effort. But somehow the organisational machinery got moving anyway. Masterpieces arrived at the Rocca in absolute secrecy from all over Italy. Even if around the castle there was a continual movement of wooden boxes arriving day and night, no one amongst the German and fascist spies suspected anything. The plan worked perfectly.

|

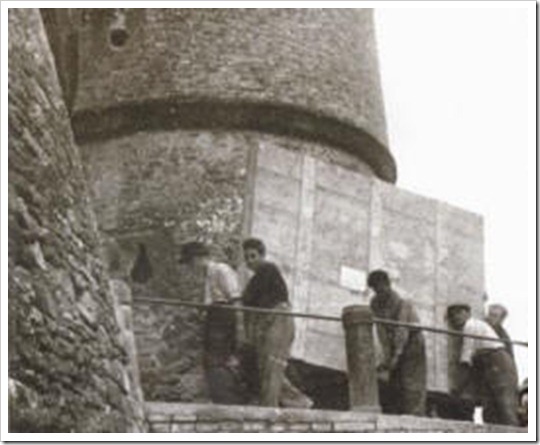

| One of the lorries used to transport the works of art. – |

| –A treasure of immense value |

Mentre il conflitto divampava sempre più e le città venivano bombardate da Sud a Nord, l’arrivo dei capolavori cresceva senza sosta. In totale le casse furono 7 mila: Giotto, Raffaello, Tintoretto, Bernini. Un tesoro dal valore immenso. «Le assicurazioni si sarebbero rifiutate di offrire una polizza» scrisse Rotondi nelle sue memorie. A un certo punto, la Rocca non bastò più costringendo Rotondi a cercare nuovi luoghi sicuri che trovò nel castello di Urbino e nei sotterranei del Palazzo dei Principi di Carpegna.

Whilst the conflict blazed ever fiercer, and cities from the South to the North were bombarded, the arrival of masterpieces continued to grow. In total, there were 7 thousand boxes: Giotto, Raphael, Tintoretto, Bernini. A treasure of immense value. “The insurance companies would refuse to offer a policy” wrote Rotondi in his memoirs. There reached a point when the Rocca wasn’t sufficient, forcing Rotondi to look for other safe places, which he found in the castle of Urbino and the Palazzo dei Principi di Carpegna.

|

| Another masterpiece arrives at la Rocca. – |

| –Sometimes you need a bit of luck |

Le SS giungono a Sassocorvaro, controllano il contenuto di alcune casse che – grazie a una provvidenziale intuizione di Rotondi – sono prive di qualunque indicazione che ne chiarisca il contenuto. Certe volte ci vuole fortuna, e qui ce n’è: i tedeschi aprono una cassa che contiene “solo” spartiti originali di Rossini. Il professore riesce a convincerli che in quei sotterranei è custodito unicamente materiale musicale di scarso valore. «Avessero aperto la cassa successiva avrebbero trovato una collezione di Raffaello», scriverà nelle memorie.

The SS arrived at Sassocorvaro, checking some of the boxes that, thanks to a lucky intuition by Rotondi, didn’t contain any clues that would reveal the contents. Sometimes you need a bit of luck, and here it was: the Germans opened a box that contained ‘only’ original scores by Rossini. The professor managed to convince them that only musical material of little value was stored in the underground rooms. “If they had opened the next case they would have found a collection of Raphael”, he would write in his memoirs.

|

| The formidable Rocca di Sassocorvaro – |

| –The crazy plan was to take everything to Rome |

Ma quando il fronte indietreggia sino alle Marche la situazione precipita, e il rischio che le opere italiane finiscano nelle collezioni di Hitler e Goering è fortissimo. A questo punto comincia la seconda parte del salvataggio che si colora ancora di più di spy story. Il piano folle è quello di portare tutto a Roma, al sicuro in Vaticano. Bisogna però farlo sotto il naso dei tedeschi. Funzionerà. I capolavori vengono stipati nella Rocca. I tedeschi sono sempre più insospettiti da quei trasporti, e le rassicurazioni di Rotondi paiono non bastare più. Intanto il fascismo è crollato, il Re è fuggito al Sud, lo Stato non esiste più. Rotondi non si scoraggia, e si rivolge a una suo carissimo amico, Carlo Giulio Argan, funzionario del ministero dell’Educazione.

But when the front line moved back to the Marche region the situation went downhill, and there was a high risk that the Italian works would end up in the collections of Hitler and Goering. At this point the second part of the rescue began, becoming even more of a spy story. The crazy plan was to take everything to Rome, and the safety of the Vatican. It was necessary however to do it under the noses of the Germans. It worked. The masterpieces were crammed into the Rocca. The Germans were increasingly suspicious of the transports, and Rotondi’s reassurances didn’t seem to suffice any more. In the meantime, Fascism collapsed, the King fled to the South, the State didn’t exist anymore. Rotondi wasn’t discouraged, and he turned to one of his dear friends, Carlo Giulio Argan, an official of the Ministry of Education.

|

| Works of art arrive at The Vatican – |

| –“I should have you shot for what you did” |

Argan incontra Montini, futuro Papa Paolo VI, e insieme riescono a trovare camion e operai che raccoglieranno i capolavori da Sassocorvaro per portarli al sicuro Oltretevere. C’è anche una scorta di SS alle quali viene raccontato che le casse contengono materiale del Vaticano. Invece è quasi tutto dello Stato Italiano. Un ufficiale nazista più sospettoso viene in qualche modo “raggirato” dalla moglie di Rotondi, che la sera prima della partenza della colonna da Sassocorvaro lo fa ubriacare. Al suo risveglio i camion sono tutti lontani, diretti verso Roma. Alla donna, l’ufficiale dice: «Per quello che ha compiuto dovrei farla fucilare. Ma non lo farò». In serata Rotondi riceve un telegramma dal Vaticano: I camion sono arrivati. Tutto a posto. L’incredibile “missione impossibile” è riuscita. I capolavori italiani sono al sicuro.

Argan met with Montini, the future Pope Paul VI, and together they managed to find lorries and workers to collect the masterpieces from Sassocorvaro and take them to the safety of Oltretevere (The Vatican). They even had an SS escort who had been told that the boxes contained materials belonging to the Vatican. But in reality it nearly all belonged to the Italian Sate. A suspicious Nazi officer was somehow duped by Rotondi’s wife, who got him drunk on the evening before the convoy left Sassocorvaro. By the time he woke up the lorries were all far away, on their way to Rome. The officer said to the woman “I should have you shot for what you did. But I won’t”. That evening Rotondi received a telegram from the Vatican: The lorries have arrived. Everything o.k. The incredible ‘Mission Impossible’ had succeeded. The Italian masterpieces were safe.

If you like to know more about this exploit, and practice your listening skills, here’s an hour long video produced for Italian television: La Lista di Pasquale Rotondi

Lastly, it’s important to remember that Rotondi was only one of hundreds of virtually unknown brave Italians who risked their lives to save Italy’s Artist Heritage.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

William Auge:

Ciao Geoff, this is a good follow up article. I have pondered the contradiction of men that caused so much suffering and destruction also loving art. My conclusion is they may have been able to see the beauty in the works of art, but what it was really about was power, possession and control.

Geoff:

@William Auge I tend to agree with you Bill. I’ve read that Goering kept Tiziano’s Danae in his bedroom. Somehow it’s easier to see these infamous people as pure and simple monsters, devoid of any sensitivity. When you discover that they had a passion for beautiful pieces of art, in my eyes they somehow become both more complex and sinister at the same time.

Who knows if they really did appreciate the beauty of those stolen masterpieces, or if possessing them simply fuelled their personal megalomania.

Serena and I were discussing it, and she said that she had been disturbed years ago by a ‘happy’ family photo of Goebels with his six children, whom he and his wife eventually killed before committing suicide in Berlin at the end of the war.

At the root of so much evil is the almost schizophrenic ability of human beings to compartmentalise things in their minds, without making a connection between the different compartments.

Harriet Rose:

While in Florence last year I went walking with a man named Andrea who gives wonderful walking tours. We stopped for a coffee in a bar near the modern art museum and on the wall were photos of the day art was returned to Florence after the war. This started me on a reading adventure and I have read many books about Italy during the war. The book the Venus Fixers, written by an Italian I think, was an eye opener and probably a more balanced view than the book which if I remember was called Saving Italy by the same person who wrote Monuments Men. It is indeed a miracle that so many works survived due to the courageous and selfless acts of so many. This was a horrific and confusing time for Italians with many taking great risks to save art, Jews, partisans, and just plain fellow citizens.

Geoff:

@Harriet Rose Salve Harriet, the book which is called The Venus Fixers in English is in fact Salvate Venere! by Italian author Ilaria Dagnini Brey, who currently lives in America. I’m going to try and get my hands on a copy.

Grazie per il tuo commento, saluti da Geoff