Social Classes in Ancient Rome Posted by andregurgel on Feb 26, 2019 in Intro to Latin Course, Roman culture

Note: This blog post is a companion to Unit III of our Introduction to Latin Vocabulary course. You can learn more about the course here.

Like any other ancient civilization, the Romans had their own social classes. Although much has changed since the time of the Romans, you will notice how the Roman class system reminds us of our own societies. Indeed, as I always like to say in my articles, Rome is pretty much alive in our western civilization – a lot more than most people are aware of. On the other hand, you will note how the Roman system was mostly based on money rather than social status. We have learned from the Roman historian Polybius that the census divided Roman citizens according to their wealth and not to their birth. Thus, your social class didn’t really matter, as long as you had enough sestertii (Roman currency)!

Let’s have a look at the Roman social classes: plebeians, patricians, equites and peregrini.

Patricians: the Roman nobility

Romans referred to their nobles as Patricians, or patricii in Latin. They were originally the one hundred Roman citizens who were chosen by Romulus to become senators and assist him with the ruling of Rome. At first, the patricians were very powerful and other Roman social classes weren’t allowed to have representatives in the government. If you would like to read a short but interesting account of this, I strongly recommend the first book of Eutropius’ Abridgment of Roman History.

Although the word ‘patrician’ has become synonymous with ‘well-to-do citizen’, in ancient Rome patricians weren’t always rich. During the republic and the empire, they lost most of their privileges and being a patrician was nothing but a title. Patricians were proud of their heritage and, in some cases, they could trace their family tree all the way back to one of the original Roman senators appointed by Romulus. (and sometimes even further, like Caesar’s family who claimed to descend from the goddess Venus).

Did you know that there are people today who can trace their lineage all the way back to medieval kings and sometimes even to Roman nobility? But they are usually poor or middle class and have a nostalgic longing for the days of yore!

Plebeians

Plebeians were the majority of the population during the history of Rome. As with patricians, plebeians weren’t necessarily poor. In fact, they could rise to power and become extremely rich. Did you know that Augustus, the emperor, originally came from a plebeian family?

In the early days, plebeians weren’t represented in the government. To correct this injustice, a man named Lucius Sicinius Velletus led a rebellion against the ruling patricians. He led the Roman plebeians to Mons Sacer (the Sacred Mountain) where he had planned to found a new city, independent of Rome. Then the Roman ruling class sent an official called Agrippa Menenius Lanatus to negotiate with him. The emissary told the plebeians the fable of the belly and the limbs, in which the limbs do all the hard work but can’t survive without the belly. The negotiations led to the creation of the position of “tribunus plebis” (tribune of the plebs), the first of whom was none other than Lucius Sicinius Velletus. Tribunes were very powerful during the Republic. Apart from presiding over the concilium plebis (people’s assembly), they had the power to summon the Senate, to propose new legislation and could even veto the actions of the consuls and other magistrates. However, their influence waned during the empire.

Throughout the Republic, the plebeians continued fighting for their rights. In 133 BC, a tribunus plebis named Tiberius Gracchus proposed agrarian legislation which aimed to take away land from rich patricians and give them to poor plebeians. Unsurprisingly, he was murdered and years later his brother Caius, another tribune, suffered the same fate.

At least until the passing of the lex canuleia (pronounced ‘leks canyu-laya’), Plebeians could become very rich but they still weren’t allowed to marry patricians. Even today, marriages between people from different social classes are taboo in many societies. This is illustrated by a pun from the movie “Goodbye, Mr. Chips” in which Mr. Chips tells a tale about a patrician boy who told a plebeian girl that he couldn’t marry her, to which she answered: “Oh, yes, you can, you liar!” (try saying it with a British ‘r’). Who says that Latin teachers can’t have a sense of humor?

Equites

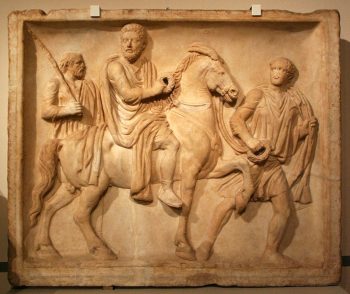

Equites comes to us from the Latin word equus (horse), hence, equites means knight or cavalryman. According to the historian Titus Livius, equites were originally provided with a sum of money by the state to purchase a horse for military service and for its fodder. This was known as an equus publicus. Legend says that the equestrian order was created by Romulus himself, although at that time only patricians were allowed to serve as knights in the Roman army. By around 400 BC, plebeians were allowed to serve in this unit of the Roman army, but they were required to be extremely rich to join. In the late Republic, a plebeian had to have a yearly income of at least 50,000 denarii to qualify as an equites. The emperor Augustus doubled this to 100,000 – about the equivalent of the annual salaries of 450 contemporary legionaries. If for some reason they could no longer make that amount of money, they were stripped from the equestrian order.

At first, ‘equites’ was nothing but a title, but it soon became a social class of its own, filling the senior and administrative posts of the government. When the Lex Claudia restricted commercial activities by senators, the equites saw an opportunity to rise socially and became great businessmen.

Of course, there are no equites anymore, but the horse is still considered a symbol of nobility in the army and horsemanship remains an activity linked to nobility. Although, as shown in this article, this was not always the case.

Peregrini

The word peregrinus comes from the adverb peregre (“from abroad”), composed of per (“abroad”) and agri, the locative of ager (“field, country”). Therefore, the peregrini were foreigners who lived in Rome and weren’t considered Roman citizens.

They weren’t entitled to the same rights as the Roman citizens. They weren’t allowed to get married and couldn’t serve in the Roman army (except in the auxiliaria troops). The peregrini couldn’t participate in political life. They were forbidden from voting or holding public office, and could be tortured and even be put to death without a trial.

The peregrini constituted most of the population in the Roman provinces. Rome probably thought that they might start a rebellion so, at first, Julius Caesar granted Roman citizenship to all the peregrini in Transalpine Gaul. A few centuries later, the emperor Caracalla issued a decree which allowed all peregrini to acquire Roman citizenship. That’s how the first and second-class citizen system ended. On the other hand, there have been second-class citizens in many parts of the modern world. See what happened in South Africa with apartheid and even the racial segregation in America.

Would you say the Roman state was a democracy or a plutocracy? Should we preserve more of the Roman customs or should we try to build a government “of the people, by the people and for the people”, as Abraham Lincoln said in the Gettysburg Address?

GLOSSARY OF LATIN WORDS AND TERMS

sertertii– Roman currency

Mons Sacer- a hill in Rome, Italy on the banks of the river Aniene,

concilium plebis- people’s assembly

tribunus plebis– tribune of the people. Represented Roman plebeians.

Lex Canulea– law which authorised marriage between patricians and plebeians

Lex Claudia– law which restricted commercial activites by senators

denarius– main currency during the Republic

peregrini– foreigners

auxiliaria (plural of auxiliarium)- non-citizen troops in the Roman army.

REFERENCES

Eutropius’ Abridgment of Roman History

Livy’s Books of the Foundation of Rome

The Gettysbury Address. Available at http://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/gettysburg.htm

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.