Caesar’s Civil War Posted by jamie on Feb 26, 2019 in Intro to Latin Course, Roman culture

Note: This blog post is a companion to Unit XI of our Introduction to Latin Vocabulary course. You can learn more about the course here.

The Death of Pompey

On or around October 1st, 48 BC, Gaius Julius Caesar sailed into Egypt. He had just won perhaps the greatest military victory of his life, and he had tracked his defeated opponent here, hoping to capture him. As he disembarked from his ship, a man ran up to him, carrying an object wrapped in a bloody linen sheet. As Caesar looked on, first with curiosity, then with horror, the man unwrapped the linen to reveal the severed head of Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus. Caesar burst into tears.

Pompey was the man he had defeated, the man he had tracked down, the man whose death now made him unquestionably the most powerful man in Rome. They had once been friends, allies, family—and then mortal enemies, each leading an army of Romans against the another in a bitter, bloody civil war. How had it come to this?

Ordines

There were two ordines, or social classes, in ancient Rome: the plebs, the lower class; and the patricii, the upper class, which dominated the Senate and the political offices of the Roman Republic.

According to legend, the Roman Republic was founded in 509 BC, after the last King of Rome was driven out of the city. As a republic, Rome was ruled by Senatus Populusque Romanus, ‘The Senate and the People of Rome,’ rather than by a single king. However, the republic wasn’t a democracy in the sense we know today. Although there was voting, and elections were open to all citizens, the votes were weighted—you could even say ‘rigged’—so that only the votes of the upper class actually counted.

Although the plebs fought for, and eventually achieved, political equality with the patricii, they were still much poorer. The patricii controlled most of the land in Italy, and the plebs had almost none. In those times there was almost no way to have money without having land.

Around the year 100 BC, two political parties began to emerge: the Optimates and the Populares. The Optimates (from the Latin optimus, ‘best’) believed that Rome should continue to be run by the patricii and the Senate, and that the wealthy should be able to keep their lands. The Populares (from the Latin populus, ‘people’), on the other hand, believed that the plebs should have greater political and economic power, and that land should be redistributed from rich to poor.

Two of these populares, brothers named Gaius and Tiberius Gracchus, were assassinated by the patricii for their support for redistributing land to the plebs. This was only the beginning of the violence.

The Generals

Another popularis around this time was a plebian named Gaius Marius, who despite his low status was elected consul—president, basically—seven times. He also dramatically changed the Roman army. Before Marius, soldiers had to own property and buy their own equipment. This meant, of course, that the army had been made up almost entirely of upper-class citizens. (There were poor soldiers, called velites, who fought wearing basically no armor at all!) Marius changed all this. He stipulated that the Roman state would provide weapons, training, a salary, and land after a soldier retired. As you can imagine, poor Romans rushed to enlist. For the first time, they had a way to move up in the world.

These changes made the army a much larger and more effective fighting machine—and it made the soldiers love Marius. Other Roman generals noticed and started buying the loyalty of their soldiers, too, by promising them a share in the spoils of war, and land after retirement. Soon, soldiers became more loyal to the general who was paying them than the country they were fighting for. And that’s how the bellum civile (civil war) began.

Marius and another Roman general, Sulla, went to war against each other in 88 BC. Marius was a popularis and Sulla was an optimas, but really both of them just wanted to be in charge, and both had armies fiercely loyal to them. First Sulla, then Marius, invaded, occupied, and pillaged the city of Rome—a Roman army sacking Rome!—and after Marius’ death in 86 BC his allies continued fighting until Sulla’s ultimate victory in 83 BC. After his victory, Sulla became dictator—absolute ruler—and killed thousands of Roman citizens.

Sulla died not long after becoming dictator, and the Romans absolutely hated him. But he had become a powerful general, and then an absolute ruler, by buying the loyalty of his troops. Pompey and Caesar, who were young and ambitious men at the time, were taking notes.

Caesar’s Civil War

As first Pompey, then Caesar, used Marius’ and Sulla’s methods to win their troops’ loyalty, the Roman Republic became weaker and weaker. The Senate lost all ability to control its generals. After Caesar crossed the Rubicon, in 49 BC, the Senate and Pompey, who had agreed to fight for the Optimates, panicked and fled to Greece. Caesar, like Marius and Sulla before him, seized Rome with a Roman army, although this time it was bloodless.

As Pompey and the Senate regrouped in Greece, Caesar raced to Spain to quash Pompey’s allies there, then turned back to pursue Pompey. He landed his armies in Illyricum, which is in Albania today, and was quickly defeated by Pompey at the battle of Dyrrhachium. Caesar retreated, but Pompey chose not to pursue, thinkingly incorrectly that Caesar was laying a trap for him. Both armies worked their way south and east, into central Greece, before finally engaging in…

The Battle of Pharsalus

Pompey saw that Caesar’s army was small, weak, and running out of supplies. Meanwhile the army of Pompey and the Optimates had twice as many infantry, five times as many horsemen, and the support of the local population. Pompey figured he could wait Caesar out. But the Senators wanted Caesar crushed as soon as possible, and they forced Pompey to make a stand.

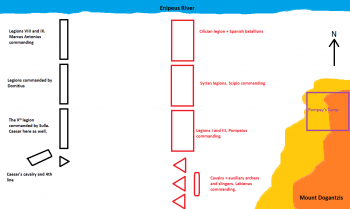

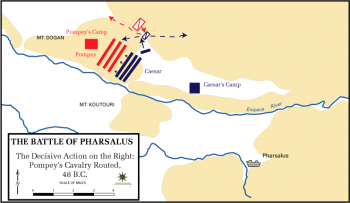

On a flat plain in Pharsalus, Greece, just south of the river Enipeus, Pompey arrayed his legions into three wings ten lines deep, with his cavalry south of the last infantry wing. He was planning to execute the hammer-and-anvil tactic: wait for Caesar’s infantry to charge across the wide plain and then, when they were exhausted by the sprint, send his cavalry out behind them, first overwhelming Caesar’s much smaller cavalry and then smashing Caesar’s infantry between the hammer of the cavalry and the anvil of his own well-rested, larger infantry.

Caesar had been going to position his legions and cavalry in the same way as Pompey’s, but after seeing the size of Pompey’s army, he thinned out each wing and created a fourth, which he placed behind his cavalry.

For a while, nobody moved. At last, Caesar gave the order to charge. Two of the three main wings moved forward while the third waited in reserve; the fourth stayed where it was, behind the cavalry.

As Caesar’s infantry charged, Pompey sent his cavalry out to attack Caesar’s. Caesar’s cavalry retreated—and the fourth wing sprang into action. Using spears called pila, the fourth wing stabbed up at the horses, terrifying the ones they didn’t kill. Pompey’s cavalry panicked, scattered, and fled. Meanwhile, Caesar’s two charging infantry wings had stopped mid-charge, caught their breath, and then continued the attack with more energy than Pompey had expected. With Pompey’s cavalry ‘hammer’ neutralized, Caesar sent his third main wing against Pompey’s third wing. Caesar’s men smashed through Pompey’s lines, and that was that: Pompey’s remaining forces broke and ran for their lives.

Pompey rushed back to camp, grabbed his family and his gold, disguised himself as a common soldier, and fled to Egypt. He hoped that the rulers of Egypt would support him and the Senate, but instead they killed him and cut off his head. They thought that this would get Caesar on their side, but they were wrong: not only did Caesar weep when he saw Pompey’s head, but he also tracked down his killers and put them to death.

Aftermath

Pharsalus wasn’t the end of the war, but it was the decisive battle. For the next three years Caesar fought in Africa, Spain, and Turkey—after the extremely short battle of Zela, in modern Turkey, he famously said ‘Veni Vidi Vici,’ ‘I came, I saw, I won’—but by 45 BC it was officially over. Gaius Julius Caesar was the supreme ruler of Rome.

Then he did a very unusual thing, which historians have been puzzling about ever since. Instead of wiping out his enemies, as Sulla had done, he pardoned almost all of them. He himself said that he had ‘no intention of imitating Sulla’, and that he wanted to ‘armor himself with mercy and generosity.’ No one really knows why he did this. Maybe he wanted to end the decades of bloodshed; maybe he wanted to keep his enemies close; maybe, deep down, he was really a softie at heart.

Whatever the case, the armor of mercy and generosity didn’t protect him for long. On March 15th, 44 BC, Caesar was stabbed to death in the street by over thirty Optimates. Several of his murderers were men he had pardoned. These assassins hoped, by killing Caesar, to make the Senate powerful again. Instead, they caused yet another civil war, which would ultimately cause the end of the Roman Republic.

Ancient history can seem weird and distant, but many of the issues that led to the Roman Civil Wars continue to be issues today. What’s the fairest way of distributing wealth, and who gets to decide that? Who actually speaks for ‘the people’? How do you stop power-hungry people from gaining power?

If you had been alive during the Roman Civil War, whose side would you have been on?

Glossary of Latin Words and Phrases

Bellum Civile—civil war. Rome suffered a number of these between 88 BC and 27 BC

Consul—equivalent of the Roman president; there were two each year.

Dictator—an absolute ruler, who is given permission under Roman law to do whatever it takes to deal with a crisis.

Optimas—a supporter of the patricii and the power of the Senate; plural form Optimates

Ordo—Latin for social class; plural form ordines

Patricii—The Roman upper classes

Pharsalus—the location of Caesar’s decisive victory over the Pompey and the Optimates

Pilum—usually a throwing spear, used by Caesar as an anti-cavalry weapon at the Battle of Pharsalus

Plebs—The Roman lower classes

Popularis—an opponent of the patricii and a supporter of the plebs; plural form Populares

Senatus Populusque Romanus— ‘The Senate and the People of Rome,’ the motto of the Roman Republic. The abbreviation SPQR is still part of the city of Rome’s coat of arms.

Veni Vidi Vici— ‘I came, I saw, I won,’ Caesar’s famous line after winning the battle of Zela in a matter of minutes

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.