Caesar and Pompey Posted by jamie on Feb 15, 2019 in Intro to Latin Course, Roman culture

Note: This blog post is a companion to Unit IX of our Introduction to Latin Vocabulary course. You can learn more about the course here.

Bellum Civile

In the middle of the 1st century BC, the Roman world was plunged into war, not for the first time, and certainly not for the last. This bellum civile (civil war) wasn’t only over who would rule the Roman people, but how. On one side were the Optimates, who supported the nobility in the Senate. On the other side were the Populares, who supported the lower classes, known as plebs.

This bellum civile was bloody but very short, and each side was led by a brilliant commander. In this corner, for the Optimates and the Senate, one Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus; in the other, for the Populares, Gaius Julius Caesar. Today we know them better as Pompey the Great and Julius Caesar.

Gnaeus Pompeius

Pompey was born in 106 B.C., to a rich family from Picenum, a town on the opposite side of Italy from Rome. At that time only people born in the city of Rome itself were considered true Romans, so Pompey was always something of an outsider in Rome. He didn’t let that stop him, though—Pompey wasn’t the kind of person to let anything stop him.

He did more or less one thing in his life, and he did it very, very well: he won battles. He was a general from the age of twenty, and never stopped being one until the day he died.

He went to Sicily and destroyed some rebels there, and then he went to Africa and wiped out some more. He was so vicious people started calling him adulescentulus carnifex (the little teenage butcher) and so successful they started calling him Magnus (the great). After his victories in Africa, he wanted to come back to Rome and have a triumph.

A triumph (triumphus) was a parade through the streets of Rome, led by a Roman general who had won a major victory. However, only a consul—sort of like the President of Rome—could lead a triumph, and Pompey wasn’t a consul. He wasn’t even old enough to run for consul (Consuls had to be at least 42 years old). And besides that, Pompey was completely ignoring the cursus honorum—which is sort of like the career ladder all Roman politician had to climb before they could become consul. Pompey thought he was too good for that.

So when Pompey was told no, he went ahead and did it anyway. He even tried to ride a chariot drawn by elephants, but they couldn’t fit through the gate!

After this Pompey continued to fight pretty much everyone pretty much everywhere, and won every time. He fought in Northern Italy and in Spain. He destroyed a slave rebellion in Italy and crushed the pirates who terrorized the Mediterranean Sea. He conquered cities and overthrew kings in Armenia, Syria, and Judaea. (People in Syria liked him so much they named a dating system after him—as if, instead of A.D., like we use today, they used A.P.: in the year of Pompey)

In 61 BC Pompey returned to Rome and got his third triumph (after the one for Africa and a second one for Spain) for his victories in Syria. It was the biggest, most lavish, and longest triumph in the history of Rome; to the Romans it must have seemed like Pompey had conquered the entire world. And then Pompey went to the Senate and asked them to vote to give land to the soldiers who had fought for him. The Senate said no. So Pompey, never one to give up, turned for help to the consul, a fellow named…

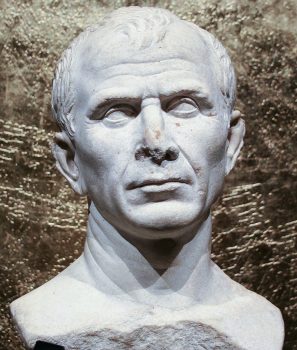

Gaius Iulius Caesar

Julius Caesar war born in Rome in 100 BC, and like Pompey he lost his father as young man. Unlike Pompey, Caesar wasn’t a brilliant general right away, but he was incredibly charismatic, smart, and ruthless.

There is a story that, around the age of 22, Caesar was sailing across the Aegean Sea when he was captured by pirates. (This was before Pompey destroyed them all). The pirates knew he was rich, so they demanded a ransom of 20 talents (something like $500,000). Caesar was outraged. “I’m worth at least 50 talents!” he cried, so that’s what the pirates asked for. After the ransom was paid and Caesar was released, he hired a fleet of ships, hunted down the pirates, and had them crucified. He did have their throats cut first, though, so they wouldn’t suffer. In some ways, Caesar was always a nice guy.

Caesar worked his ways slowly through the ranks of Roman politics, following the cursus honorum that Pompey ignored. In 60 BC, when he finally became consul, Pompey asked him to become allies. Pompey had the military muscle, Caesar had the political connections, and a third man, Marcus Lucinius Crassus, the richest man in Rome, had the cash. Together, they made a Triumvirate, or dictatorship of three, sealing their alliance with the marriage of Pompey to Caesar’s daughter.

Pompey wanted to give land to his troops, and Caesar wanted to give land to the poor. (I told you he was a nice guy). To do this, they would have to pass a law seizing land from the rich. The fight was brutal. Literally: People were threatened and bribed and beaten, and a consul had feces thrown on him. In the end the law was passed, but when his consulship was over Caesar quickly left town, afraid that the many rich enemies he had made were going to come after him. He was made general of the Roman armies in Transalpine Gaul (Southern France) and was supposed to stay for five years. He stayed for nine, and by the end he had conquered all of Gaul (France).

After the war in Gaul was over Caesar returned to Italy. There was a law that no general could enter Italy while he still had an army with him, so the Senate warned Caesar to step down before he crossed the Rubicon river, which was the northern border of Italy. Caesar was still afraid of his enemies back in Rome, so he refused, and on the evening of January 10th, 49 BC, Caesar and his army approached the Rubicon river. No one really knows what happened then. He may have stopped and waited, debating with himself; he may have stormed right across the river; he may have seen a vision of an enormous figure playing a flute. Whatever happened, he, together with his army, crossed the river that night. “The die,” Caesar said, “has been rolled.”

It’s War

After Caesar crossed the Rubicon, everyone knew there was going to be a civil war. The Senate needed a great general to fight for their side. So they turned to a man many of them hated and feared, a man who had totally ignored the laws and customs of the Roman state. They turned to Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus.

It was inevitable, now: it was going to be war, it was going to be Caesar against Pompey, and it was going to end in victory or in death.

GLOSSARY OF LATIN WORDS AND TERMS

Consul—the chief executive of the Roman state. Sort of like the U.S. President, except that two were elected for one year at a time.

Cursus honorum—the career ladder for Roman politicians. Before you became consul, you had to hold at least three other offices.

Bellum civile—civil war

Optimates—the political party that supported the nobility and the senate

Populares—the political party that supported the plebs or lower classes

Plebs—the lower classes

Triumphus—a triumph, or victory parade for a Roman general

Adulescentulus carnifex—‘teenager butcher’; a nickname that young Pompey earned for his viciousness in battle

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.